Inaccessible, inadequate, unaffordable, undignified, insecure or absent housing are conditions feeding the downward spiral of individual and societal deprivation. In Europe such conditions affect a growing number of people in different ways. Public authorities carry responsibility for dealing with a problem, not due to individual circumstances but rather a lack of housing, welfare failures and predatory market-oriented practices.

Housing NOT for all

According to Eurostat, 82mil people are affected by the housing overburden rate, meaning they spend over 40% of their disposal income on housing costs. House prices are rising throughout Europe, whereas incomes are mostly stagnating. Meanwhile homelessness is on the increase almost everywhere.

The most comprehensive analysis on homelessness in Europe was provided by the “Third Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe” report by the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (Feantsa) and the French Abbe Pierre Foundation. It provides a gloomy picture of homelessness skyrocketing across Europe, with the highest rates being 169% in England, 150% in Germany and 145% in Ireland.

In particular, in Germany, the BAG W (the umbrella organisation of non-profit homeless service providers) estimated there were 860,000 homeless in 2016 with a prognosis of 1.2 mil for 2018, a further 40% increase due to asylum seekers. In Ireland 8,897 were estimated to be in shelter accommodation, and 3,333 children were registered as homeless (end of 2017) which is 1 in 3 homeless being a child. Discrimination and fragility of certain groups are also largely under-studied and underrepresented by statistics such as women, LGBTIQ, prisoners becoming homeless after release, etc.

Measurement and causes

One of the main difficulties in addressing homelessness in EU, national and local public policies is the provision of accurate statistics due to the techniques used to gather them and how homelessness is defined. If accurate measurement is crucial for designing evidence-based policies, an analysis of the causes of homelessness is crucial in designing appropriate policy measures. The causes might often be hidden or misinterpreted: one of many persistent misconceptions is that homelessness is the result of individual circumstances rather than unjust inequalities in housing, welfare, public services, jobs and, above all, wealth creation and distribution.

One of the main difficulties in addressing homelessness in EU, national and local public policies is the provision of accurate statistics due to the techniques used to gather them and how homelessness is defined. If accurate measurement is crucial for designing evidence-based policies, an analysis of the causes of homelessness is crucial in designing appropriate policy measures. The causes might often be hidden or misinterpreted: one of many persistent misconceptions is that homelessness is the result of individual circumstances rather than unjust inequalities in housing, welfare, public services, jobs and, above all, wealth creation and distribution.

One of the main findings of a study by Fransham and Dorling (2018), is that one of the main causes of homelessness is the “end of private-sector tenancy”, namely the lack of affordable and adequate housing solutions. This is clearly a systemic issue depending on the housing market and its distortions.

Along the same lines Leilani Fahra, the UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, points out that the phenomenon of homelessness is dependent on how the residential real estate sector is dealt with globally.

Indeed, homelessness has to be contextualised in a discourse on wealth production and the role of government in providing leeway to unregulated financialised residential real estate markets, meaning viewing housing not as a right but as a commodity – a financial asset to leverage more capital. Contradictions are evident, according to Leilani Fahra, when linking data to national GDP. “Germany is the 4th-largest country in the EU in terms of GDP with 420,000 homeless (excluding refugees), Italy the 8th largest GDP with roughly 50,000; France 6th with 480 people dying on the streets every year” Leilani Fahra, Housing For All, Conference (Vienna 04.12.2018). Therefore, how can housing be transformed into a guaranteed right in the context of scarce affordable housing and increasing injustice?

Housing all homeless is possible

Macro-economic trends are fundamental to understand why scarcity is maintained to fuel capital, and why housing is the most profitable sector worldwide. However, at micro-economic level cities must have a say. Local governments can count on many instruments and solutions to counteract housing shortages, prevent homelessness and support every citizen starting from those most in need.

The seminar in Paris called on EU cities engaged in fighting homelessness to share their practices and experiences in designing and implementing strategies fighting homelessness.

The seminar covered the challenges of measuring homelessness, the implementation of the Housing First programme, practices of homelessness prevention, and reuse of vacant buildings.

Every thematic area was presented and debated through the experience of cities active within the URBACT programme and city administrations collaborating with FEANTSA. What follows is a glimpse at the topics and practices of some of the cities contributing to the success of the seminar.

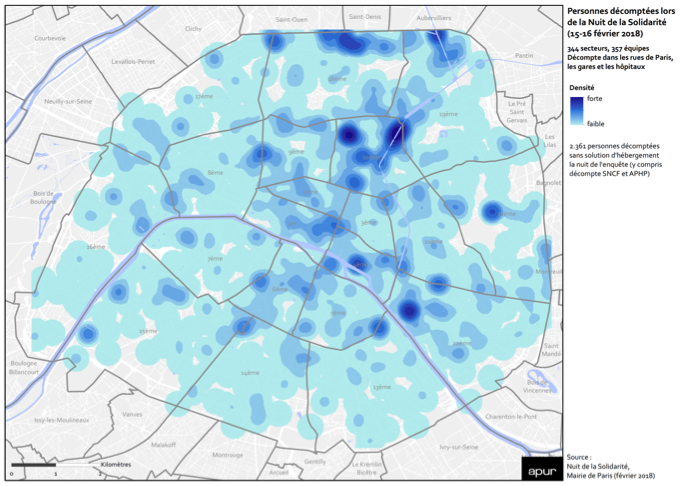

Counting homeless in Paris (FR): La Nuit Solidaire

Although homelessness falls within the jurisdiction of the French state, moral and political responsibility for homelessness is considered part of the mandate of the City of Paris under the socialist mayor Anne Hidalgo. Since 2015 the city has built a coalition of partners around a plan to fight social exclusion (Pacte Parisien de lutte contre la grande exclusion 2015-2020) and reduce street homelessness, including the recent city-wide plan to use public buildings as emergency shelters.

Although homelessness falls within the jurisdiction of the French state, moral and political responsibility for homelessness is considered part of the mandate of the City of Paris under the socialist mayor Anne Hidalgo. Since 2015 the city has built a coalition of partners around a plan to fight social exclusion (Pacte Parisien de lutte contre la grande exclusion 2015-2020) and reduce street homelessness, including the recent city-wide plan to use public buildings as emergency shelters.

Paris has 2.1 m inhabitants (metropolis 6.7 m, urban area 11 m) and provides 16,000 shelter beds with around an additional 2,000 in winter. Homelessness has been on the rise for the last 20 years. Street homelessness is highly visible, but reliable data and research are lacking. To gain a clearer picture the “La Nuit Solidaire” initiative managed by the Mayor’s Office was launched overnight between 15th and 16th of February 2018 to count the number of street homeless in its urban area by 356 coordinated teams, comprising 1 professional and 4 or 5 volunteers – with training ahead of time for the professionals and on the spot for volunteers. Around 2,000 civil servants and volunteers participated in the nocturnal count of homeless people city wide, street by street, conducting a survey to gather information on demographics, sleeping places, use of homeless services, and needs.

The results provide significant findings that both contradict and enrich the information gathered previously. According to Mme Benoit “In Paris homelessness is a phenomenon of concentration and dispersion, which concerns the whole city. The survey uncovered some significant data: for instance, it was estimated that around 5% of homeless were women, but in reality it turned out to be 12% due to fact that women tend to hide and thus are not as visible in public spaces. Moreover, the survey showed that approximately 64% of those in need do not call 115 (the number for Samusocial proving emergency support for people on the streets).” Moreover, the survey shows that the phenomenon of homelessness is closely related to spatial dynamics that differentiate location preferences in relation to age, short- and long-term experience of homelessness, recipients of 115 support, etc.

As a follow-up, every year in February the survey will be repeated, possibly extending beyond the peripheral line of Paris to the metropolitan area. The Solidarity Bubble centre has been created to host a 5-point programme to provide education on the reality of homelessness, combat stereotypes and preconceived notions; promote projects aligned with municipal priorities; provide training on homelessness and skills useful when serving them; and help volunteers connect with opportunities or test their own ideas.

Housing First: how Finland (FI) and the city of Helsinki stop homelessness

Housing First provides unconditional accommodation for people experiencing homelessness successfully applied in the United States, Canada and several European countries. “A Housing First service is first and foremost concerned with providing housing to homeless persons immediately or very quickly, combined with support tailored to the individual. Within this framework, the immediate focus is placed on enabling a person to live in their own home.”

In Europe Housing First has been successfully adopted in many cities and applied throughout Finland, the only country in Europe where homelessness has fallen. The particularity of this case is that Housing First has been adopted at national level with three main targets: halve long-term homelessness by 2011 and end it by 2015; reinforce the Housing First approach as a mainstream organising principle for housing and support services for the homeless; and convert all shelters and dormitory-type hostels into supported housing units.

The Ministry decided to take action in 10 municipalities with existing homeless shelters being gradually improved and turned into serviced flats (some with 24/7 help). Many existing old buildings in poor locations were turned into flats for the homeless: a “big hostel for the homeless in Helsinki with 250 beds was run by the Salvation Army. (Around 2014) this hostel was renovated to become 80 independent apartments with on-site staff.” There are different grades of flat: serviced flats in large buildings or scattered flats with no service across the city, owned by the Municipality or housing associations, which through loans from the Municipality allow new flats to be built. Tommi Tolmunen, a Helsinki social worker, points out that “this is different to the staircase model in which escaping homelessness is the result of good behaviour. In Housing First the initial step is to hand over a key and say let’s talk when you’re ready…” An important change was the moral attitude toward the provision of support: “to stop taking drugs and get treatment for alcoholism is no longer a precondition for a flat”.

Today all units are full and waiting time is over a year. “The problem is that people are not moving out from these units as fast as those wanting to move in…” Tommi Tolmunen. Alternative housing solutions and flexible support and services are the next challenges for a thus-far-successful method, from which other EU cities are learning (see Housing First Europe Hub).

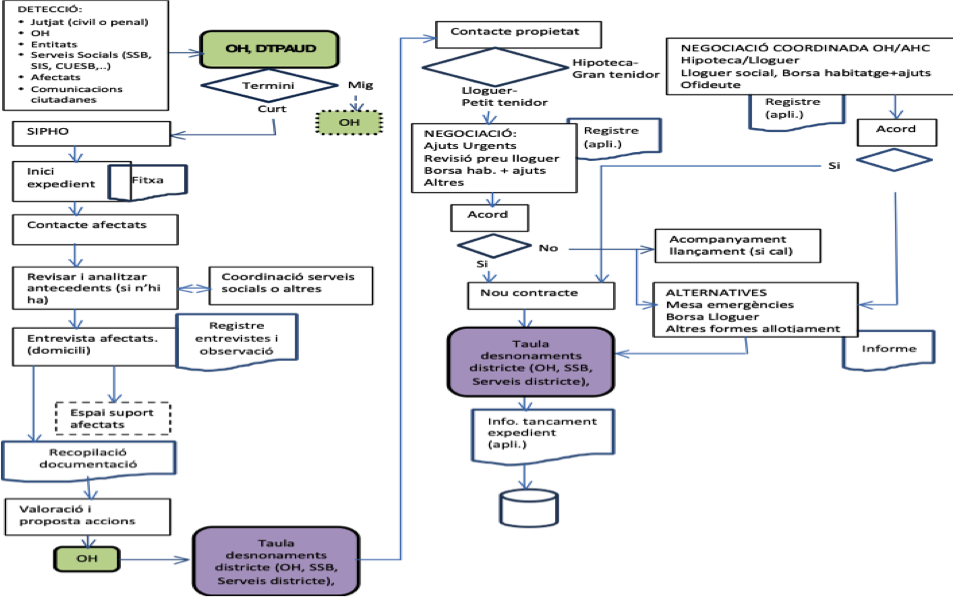

Prevention of homelessness: Strategy against eviction in Barcelona (ES)

The city of Barcelona is one of the best examples of public policy being implemented to combat housing speculation. From the period of booming investment in the late nineties up to the financial crisis, the real estate sector witnessed a flurry of speculation leading to mass evictions (Coq-Huelva, 2013; García‐ Lamarca and Kaika, 2016): Between 2008 and 2015 there were 35,234 evictions in Barcelona. The city has 1.7 m inhabitants (metropolitan area 3 m) and less than 1.5% social housing. Since 2017 rent has increased by 7.8%, house prices by 9.2%, and there have been an average of 30 evictions each week (81% rental).

The Municipality aims for more social housing but its provision is the remit of the Generalitat, the Government body of Catalonia. Despite this, the Municipality of Barcelona has formulated the comprehensive Right to Housing Plan 2016-2025 Barcelona, with a 5-point strategy to improve housing affordability, adequacy and accessibility. Among the many actions to guarantee housing as a basic right to all citizens, the Municipality is creating its own housing association, which will build on land offered by the Municipality. A special service to support people affected by eviction is provided in the Right to Housing Plan called Intermediation Service for People in the Process of Evictions and Occupancies (SIPHO), which received the URBACT good practice label. Specialised lawyers work in housing offices (13 across the city) coordinating the efforts of social services in each district. With 10 m euros of funding, these offices offer help in mediation with landlords, management of debt and arrears, legal aid, alternative housing, and advice and information. “Citizens are informed via different communication channels, and shown a graph explaining the steps they need to take within 15 days to avoid eviction”.

In 2017, this service attended 2,351 new families in residential exclusion, which represents more than 7000 people of which 2,377 were minors.

Reuse of vacant building

In 2014 a UK-based NGO calculated that there are 11 m vacant homes in Europe (over 3.4m in Spain, over 2m in each of France and Italy, 1.8m in Germany and over 700,000 in the UK).

“A ‘healthy’ vacancy rate for a housing market, both in the US and Europe, is considered to be 3 to 5 %. When vacancies rise, house prices should decrease and vice versa in response to supply and demand mechanisms. However, high vacancy rates have gone hand in hand with rising house prices especially in Mediterranean countries”. In practice, high vacancy rates to not automatically lead to reductions in house prices. Most problematic are empty dwellings likely to remain so for long periods (overoptimistic pricing, unfit for habitation / reluctance to invest in refurbishment, inheritance, health, etc., holiday home, change of occupants, voluntarily off the market).

The question of whether this housing stock can be a potential supply for the lack of affordable housing, demands different types of information and competencies regarding data about property, existing vacancy and market dynamics, expertise in urban planning, competences in legislative and fiscal conditions etc.. In particular, taxation procedures and strategic incentives can make a difference in potential use of vacant apartments: Is a discount offered if the empty apartment is rented out? Is there discount for social renting? In England, local authorities can demand a local tax increase of up to 50% for properties that have been unoccupied and unfurnished for more than two years. And in terms of incentives, some local authorities in England, suggest that owners rent their property long term (5 to 10 years) to renters chosen by the council and awards a vacant housing grant to cover 50% of the renovation costs.

In Paris, urban planning and municipal decision making, especially though the Plan to Fight Social Exclusion, have made a difference in the reuse of vacant buildings for social purposes. There are many examples such as the reuse operated by an intermediary between the space owner and the operator of activities that will be hosted during the period before redevelopment; the reuse of former hospital Saint Vincent de Paul to host shelters and charities vacant before being redeveloped as social housing. The re-use of public buildings, known to have been empty for at least 2 years, turning them into temporary shelters like the example of public buildings for homeless women managed by NGOs. However, as Gabriel Visier, who works on a day-to-day basis with NGOs, warns “the use of vacant spaces for shelters implies some challenges: there are costs in turning them into places suitable for use as a shelter (showers, kitchens…), sometimes the period the vacant building can host a temporary shelter is too short to be financially viable for the charity that will operate it (as it must to provide the investment required to make the space fit for use as a shelter, but will have little time to pay off that investment).” The necessity to relocate the shelter once redevelopment starts is also a major challenge charities are facing.

In Paris, urban planning and municipal decision making, especially though the Plan to Fight Social Exclusion, have made a difference in the reuse of vacant buildings for social purposes. There are many examples such as the reuse operated by an intermediary between the space owner and the operator of activities that will be hosted during the period before redevelopment; the reuse of former hospital Saint Vincent de Paul to host shelters and charities vacant before being redeveloped as social housing. The re-use of public buildings, known to have been empty for at least 2 years, turning them into temporary shelters like the example of public buildings for homeless women managed by NGOs. However, as Gabriel Visier, who works on a day-to-day basis with NGOs, warns “the use of vacant spaces for shelters implies some challenges: there are costs in turning them into places suitable for use as a shelter (showers, kitchens…), sometimes the period the vacant building can host a temporary shelter is too short to be financially viable for the charity that will operate it (as it must to provide the investment required to make the space fit for use as a shelter, but will have little time to pay off that investment).” The necessity to relocate the shelter once redevelopment starts is also a major challenge charities are facing.

On a smaller urban scale, the Municipality of Villafranca del Penedes (ES) created a strategy to facilitate accessibility of affordable housing through the URBACT good practice programme, which maps empty buildings, provides rehabilitation for social purposes, uses construction work for occupational training and job promotion for the unemployed, and ultimately housing for families in need. The procedure is fairly simple and has been running successfully for 25 years: first, the owners of vacant old buildings can voluntarily request to be part of the programme; second, the city council analyses each case, if fit, makes a contract with the owner who transfers the use of the building to the city council for a period of time proportional to the size of the investment; third, construction is carried out with training monitored by Social Services; fourth, the selection of beneficiary families, preferential rent up to 5 years. Since 1992 250 flats have been renovated, with 90 still managed by the municipality. Over 500 families have been helped this way, and beneficiaries are contacted every 2nd month by social services.

Contextual conditions for the programme’s success are crucial: In Vilafranca few banks are registered as home owners as it would be difficult to cooperate with them; the owners of old vacant buildings cannot easily sell their flats, and heritage law creates problems. Moreover, they are also unwilling to have flats remain empty due to the threat of squatters. As such, home owners, who cannot be forced to participate, see an advantage in joining the programme. The variety of cases and practices in the reuse of vacant buildings is manifold and context related. URBACT has produced an online tool of practices to showcase some of the solutions implemented across Europe.

Special thanks go to all the city participants ( e.g., Ghent, Manchester, Newcastle, Gothenburg, Lisbon, Thessaloniki et al.) of the seminar, which contributed cases, examples and questions from local practices to be showcased in an upcoming report.