Belgian architect Luc Schuiten envisages that in 2100 “Sustainable development will have become a pleonasm”, and as such, all urban development will inevitably be sustainable. Future cities will see new living and working habits, mobility and interfaces intersecting and co-existing with the natural environment. Local authorities will play a role in this transformative change, notably by working on infrastructure: creating green spaces out of abandoned buildings and spaces, joining the urban net, enabling a pedestrian connexion and infrastructure from one neighbourhood to another. Notwithstanding the environmental benefit of such measures, public spaces will also become spaces for creativity, learning and exchange.

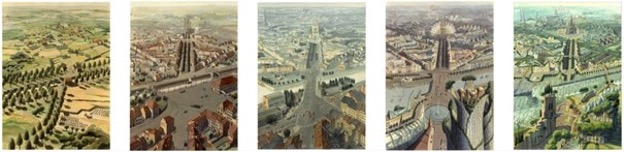

Laeken 1800- 2200, La Cité végétale, Luc Schuiten. Source: Vegetalcity.

This article looks closer at the need for green revitalisation and regeneration in the context of the URBACT GreenPlace Action Planning Network, one of 30 URBACT Action Planning Networks running from June 2023 to December 2025. Led by Wroclaw (PL), GreenPlace addresses unused, abandoned and forgotten places with green revitalisation and regeneration efforts – all involving the local community.

The issue of forgotten and unused urban spaces

The urban landscape in Europe has evolved over the last decades. Former industrial or rail infrastructures, factories, construction sites, slaughterhouses, large health and social care facilities, shopping centres, offices or incomplete buildings and city centres, former military barracks, parks and greenfields – a variety of buildings and spaces have lost their original functions, left unused, abandoned and/or forgotten.

Bucharest Delta. Source: Marcelline Bonneau.

These buildings and sites can be abandoned or unused for a variety of reasons:

- radical changes, conditioned by historical or economic events;

- negative connotations linked to places;

- the natural toll of time pr dereliction;

- social, historical and economic changes in a city;

- population shifts from rural to urban areas and changes in residential patterns (e.g. larger houses, fewer people per family unit);

- the low price of undeveloped greenfield land compared with the high cost of redeveloping land (e.g. regeneration of brownfields); or

- becoming too expensive to maintain.

Addressing the management of these under-used land, spaces and buildings is a key focal point of European regional development policy and funding frameworks. On the one hand, if nothing is done, these spaces will have a negative impact on the environment and biodiversity. For example, former storage and manoeuvring yards can form ‘heat islands’ and stored pollution can lead to further problems related to, among other things, rainwater management. Unused public spaces can also negatively impact land use, not accounting for land pressure and uncontrolled urban development (sprawl), and socio-economic inequity and insecurity.

On the other hand, if we do something, we’ll see a positive impact on the environment. Nature-based solutions, brownfield regeneration, green infrastructure and other technical green solutions – including retrofitting or energy networks – can increase biodiversity, protect habitats, attract new fauna and flora and integrate climate adaptation solutions, for example, related to rainwater management, water retention, cool islands, etc.

Cities involved in URBACT networks, such as Lille (FR) and Heerlen (NL), serve as case studies on the positive impact of greener rehabilitated public spaces in their communities. Policy recommendations for the reuse of spaces and buildings include, among others: involving architects and planners in the development of land-use plans; fixing realistic land and financial budgets; considering public-private partnership models.

The need to develop green revitalisation and regeneration

Green revitalisation and regeneration are a prominent way of addressing unused, forgotten and abandoned places, both as a means to sustainable urban development and ends in themselves. The most common principles underpinning these concepts are addressed in the following approaches:

| Approach | Explanation |

| Circular Cities |

|

| Nature-Based Solutions and Green Infrastructure |

|

| Cultural Heritage as a Resource |

|

GreenPlace: 10 cities revitalising forgotten urban spaces with local communities

The above approaches to green revitalisation and regeneration form the core of the GreenPlace Action Planning Network. Led by the City of Wroclaw (PL), partner cities include Boulogne-sur-mer Développement Côte d’Opale (FR), Bucharest-Ilfov Metropolitan Area Intercommunity Development Association (RO), Cehegin (ES), Limerick (IE), Löbau (DE), Nitra (SK), Onda (ES), Quarto d’Altino (IT) and Vila Nova De Poiares (PT).

The variety of partner profiles stresses the richness and added value of such a diverse partnership. Some of these cities are small (e.g. Vila Nova de Poiares has 7.281 inhabitants) others are very large (e.g. Bucharest-Ilfov, with 2.298.000 inhabitants). Some are rural areas (e.g. Quarto d’Altino), some are very urban (e.g. Wroclaw), while others are considered developed (e.g. Limerick) or less developed (e.g. Nitra).

The partner cities may be in different stages of green revitalisation and community engagement. They may face different contexts and challenges, as indicated in the GreenPlace baseline study, which details the context, methodology and roadmap of the Action Planning Networks. Regardless of these differences, they are already learning so much from each other!

In particular, city partners are focusing on the following main categories of forgotten and unused urban spaces:

- Abandoned buildings: a Noodle Factory in Löbau, a Civic Centre in Quarto d’Altino;

- Forgotten buildings (yet, partially in use): the Popowice Tram Depot in Wroclaw, the Victorei Tram Depot in Bucharest-Ilfov;

- Unused green areas: a medieval wall in Limerick, a Green Zone in Vila Nova de Poiares, Ejidos in Cehegin; and

- Unused built areas: a future Green Lung in Onda, the Station-Bréquerecque area in Boulogne-Sur-Mer, Martin’s Hill – a former military barracks site in Nitra.

In Löbau, partners have reported back on involving the local community in plans to revitalise an abandoned factory site.

URBACT Action Planning Networks: greener horizons

More updates are still to come from the GreenPlace Action Planning Network as the work progresses.

In the broader scheme of the URBACT IV programme, GreenPlace is not the only URBACT Action Planning Networks making cities greener. COPE, Let’s Go Circular, BiodiverCity, Eco-Core and In4Green are a few others worth exploring!

This article was updated in April 2024. The original version was submitted by Marcelline Bonneau on 19/12/2023.