New York as a reference

The New York city ID is considered as a reference by many European cities, as it is probably one of the most powerful expressions of urban citizenship worldwide: it enables all New Yorkers to identify themselves to educational and other public services, to city police officers, to employers, to partner banks, when signing contracts for mobile phones or apartments or for vaccination and it entitles them to discounts for cultural services. The ID is issued based on local residence, regardless of migration status. But it has not become a substitute identityfor undocumented migrants: it has 1.3m users, corresponding to 15% of the city’s population.

To initiate the exchange of experiences in Europe, Lea Enon-Baron from the National Association of welcoming cities and territories (ANVITA) provided an overview about the promotion of city cards in France. With Villeurbanne as a pilot experience, a first card was introduced with the support of ANVITA in 2023. Other cities such as Lyon, Rouen and Grenoble are currently preparing similar cards. A key lesson has been learnt through these first experiences : while they cannot provide regularisation or a protection from deportation, they can nonetheless make day-to-day life easier for migrants with a precarious status. Actors working on local cards should agree on their goals, find a balance between symbolic and practical aspects and engage in a process of increasing the power of the card by getting more and more services on board. The introduction of city cards needs to be accompanied by training and awareness raising with the wider population, so that cards are better accepted and reach their full potential (see also the 2021 ANVITA report on city cards - FR).

Bern: improving effective access to rights

Sarah Schilliger from Bern University presented the experience of Zurich and of Bern, drawing on her experience as coordinator of a feasibility study commissioned by the city of Bern. Bern has about 140,000 inhabitants, 25% of whom do not have Swiss citizenship and around 1,000 to 1,500 whom are estimated undocumented. The development of a city card was put onto the city's agenda by a civil society coalition “We are all Bern” in 2016. It was then quickly taken up by a city councillor in 2017 and subsequently made it into the city’s plan of integration priorities, with the support by the city’s social affairs department and the police inspectorate:

"The City of Bern participates in the debate on the concept of 'Urban Citizenship' and is committed to introducing a City Card in order to promote the participation of all residents of Bern, regardless of their citizenship status.“

After this jump start, however, the project got bogged down in what Schiliger called the “techocracy trap”: an analysis of the project through the public administration showed that many key competencies, such as police and health care, were beyond the city's reach, as they were under the control of administrations less supportive of the project. So according to Schilliger, the future Bern card will probably not provide access to new rights and services, but rather ensure better access to existing ones. Developing the digital format of the card is a priority included in Bern’s smart city strategy and city app.

One of the key lessons learnt from Bern is the importance of civil society’s support. The inclusion of trade unions in the work has been instrumental in linking the card to the area of work.

Liège: a window of opportunity

Illustration credits: @rographi

The starting point for WELDI partner Liège was similar to Bern’s : under the label of “Liège Welcoming City”, a coalition of civil society actors put a “Carte Ardente” onto the local agenda. The city council unanimously adopted a Welcoming city resolution in 2017. A working group “Carte Ardente” has been created under the coalition, which produced a comprehensive study outlining legal and practical aspects of the introduction of the “Carte Ardente”. Workshops organized in 2023 and 2024 promoted the project with citizens and services. Today, the WELDI project and the renewal of the local government provide an opportunity to finally launch the card. The city department for Sport, libraries, the health relay for undocumented migrants and the regional Integration center (CRIPEL) have endorsed the project. As in Bern, the smart city policies can provide an additional push, as the card could be incorporated into Liège’s smart city app “Liège en poche” (Liège in your pocket).

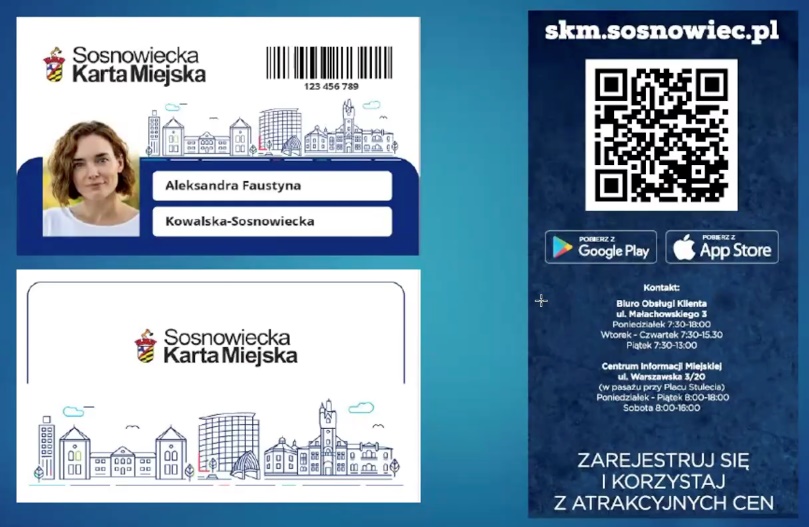

A look at city card projects and migrants in Utrecht and Sosnowiec

Utrecht is also planning to develop a new city card specifically for undocumented migrants, in order to avoid duplicating the existing U-Card for people receiving social benefits. The city wants to combine the city cards with the city rights app currently used by Amsterdam to better inform people without residence permits about their rights. The idea is to develop the card gradually, adding new affiliated municipal services as they become available. One of the functions would be to offer discounts for sports and cultural events. Another one would be to provide the Aliens Police with information about the card holder being in a process of consolidating their status, to avoid deportations. Utrecht is planning to discuss the proposal with politicians in the first half of 2025 and at the same time discuss acceptance of other municipal departments and local NGOs.

In Sosnowiec, the objective is to build up on an existing city card introduced in 2022 (both in plastic and digital) to foster participation of migrant residents. The Sosnowiec card offers discounts for sports and cultural events and identification in local services. There are also plans to link the app with an app that works at national level and allows identification.

There are currently 37,000 city card users (roughly a quarter of all eligible residents), of whom only 200 are non-Polish residents. By increasing the number of migrant residents among card users, the city hopes to strengthen their sense of belonging to the city and to foster their participation and interaction with established residents. In a survey conducted this year with migrants, only about half of them knew about the card. Access procedures may pose an obstacle for migrants, as the criteria for obtaining the card require either permanent residence status or tax payments—conditions that could exclude some of the Ukrainian refugees, who make up the city's largest migrant group. So through its Integrated Action Plan, Sosnowiec will work on facilitating access to the card and raising awareness about its benefits among the city’s migrant population. There are expectations from citizens to strengthen the functionalities of the card, and the city will explore step-by-step how to go further based on what has already been achieved.

An idea whose time has come?

The workshop showed that city cards have become a key tool for city authorities to strengthen urban citizenship accross its interconnected dimensions of status, rights and identity, and to mobilise local resistance against attempts to curtail human rights. While none of the European city card projects is likely to reach the standard of the New York ID, all believe in the city cards’ potential to strengthen the effective access to rights, recognition and trust.

As city cards cannot be a substitute for a residence or work permit, expectations need to be managed. But new opportunities can arise in their development. Cities discover for instance that smart city developments such as citizen apps can provide unexpected allies, momentum and funding for city cards that can improve the situation for residents with a precarious status.

Defining the functionalities of city cards should be thought of as an open process. As a representative of Liège Ville Hospitalière reminded, local autonomy as a key foundation for city cards is limitless, as long as it does not violate the competencies of other administrations. City cards are long-term projects that demand the involvement of a range of actors, including migrants with a precarious status themselves, activists who often provide the impetus for their development, but also mainstream civil society and of course city council departments.

The WELDI meeting on city cards also identified a need to further connect the actors that promote city cards. While many are linked to each other in informal networks, there is a need to consolidate these connections, in particular between activists and civil society coalitions in different cities. There could also be a case for using existing platforms such as ANVITA, C-MISE, Eurocities or the International Alliance of Safe Harbours to promote technical exchanges on city cards and give them more political visibility.