Date of label : 29/10/2024

-

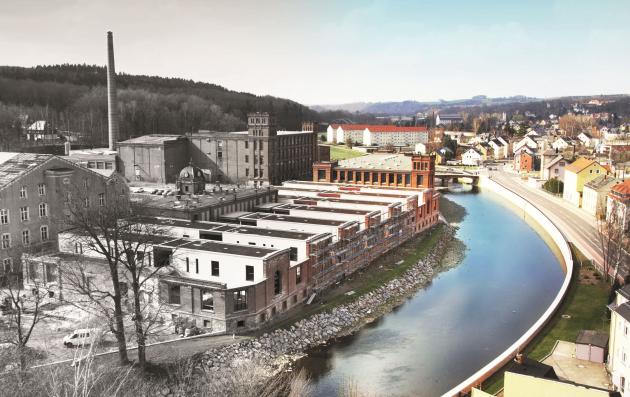

Flöha , Germany

-

Size of city : 10.500 inhabitants

This image represents Flöha, with a river flowing through it. The left side of the image is in black and white, while the right side is in color. This contrast highlights the difference between the town's industrial past and its more vibrant present.

Summary

After the millennium, the City of Flöha (DE) embarked on one of the most ambitious urban projects seen among small towns in eastern Germany since reunification: transforming a large-scale industrial estate into a new centre for the city’s inhabitants. This complex transformation integrated a multitude of strategies, focusing simultaneously on infrastructure and accessibility, marketing, attracting investors, ongoing participation processes, and establishing public functions and open spaces. Currently, redevelopment continues with housing in repurposed historic factory buildings, the design of a new market square, and restoring a former factory owner’s park.

The solutions offered by the Good Practice

Flöha is a comparatively young city. Located at the confluence of two rivers and a railway node, it became one of the hubs of the Saxon industrial belt. Several large industrial estates emerged after 1809, between three rural villages, drawing on the power of water, the available workforce, and ease of transportation. Despite its growth and significance in the region, it never developed more than a rudimentary city centre. After 1990, most of the textile and paper factories closed.

In 2001, the City decided to acquire the formidable buildings of the disused “Alte Baumwolle” (Old Cotton Spinning Factory) to develop a new city centre from scratch, based on a master plan drafted in 2006. The estate has a size of 65 000 m² and the buildings offered 40 000 m² of ground space.

For a small town like Flöha, this requires long-term commitment and flexibility – both professionally and financially – by its decision-makers in partnership with private partners and citizens. The work is financed by a mix of public (EU/Federal/State/City) and private funds. Located in the heart of Flöha, the new urban centre already hosts many public functions (City Hall, library, cultural centre, kindergarten), utilities, retail, and dwellings.

Building on the sustainable and integrated urban approach

The new multi-level development of the disused spinning factory tackles challenges related to brownfield sites: decay that spreads to neighbouring areas, ecological hazards or the structural void in the urban fabric. Most of these downsides have been successfully avoided or at least mitigated.

Investment in the former-industrial buildings and plots has become the incubator for the reinvention of Flöha, giving the city a functional centre that it never had. This has boosted economic growth, clustered public and social spaces, created modern dwellings in historic buildings, and improved the transport system. Together, these have contributed to an obvious improvement in the city’s character and identity, and supported almost all levels of integrated urban development.

Based on participatory approach

Flöha’s Refabrication project involves continuous participatory processes. These include providing information to and consulting with the local population, including special interest groups like youth and people with disabilities. For each planning step, relevant stakeholders have been included in decision-making processes, including the elected city council, providers and staff of the facilities moved to the new city centre, public agencies, and private investors.

What difference has it made?

Though the Refabrication project is not yet completed, it has already achieved much of the original aim of transforming the spinning factory into an accepted city centre for Flöha.

Before the project’s implementation, the industrial estate was a vacant and decaying void in the heart of the city. Now public functions have moved into the renovated area:

- Diverse shops in renovated buildings.

- New homes in former factories.

- A kindergarten, used by most of Flöha’s children.

- A library and a cultural centre, used by people of all ages.

- The City Hall, opened in 2024.

- A museum, to open in 2025, to bring more people into the city centre, focusing on the history of the former industrial estate and the process of cotton spinning.

- A market square, under development, as a public meeting space.

- New and improved routes between the city’s neighbourhoods, which now pass through the new city centre.

Why this Good Practice should be transferred to other cities

Flöha’s experience shows that even small towns can successfully tackle long-term projects for large-scale sustainable and innovative urban development. Other towns and cities can follow this example of the revitalisation of a disused industrial estate, through such stakeholder collaborations (public, private, and community).

The Refabrication project’s results contribute to various UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Urban Agenda for the EU, the EU Territorial Agenda, and the New Leipzig Charter, through the integration of environmental sustainability, social cohesion, and economic development.

The practice does not specifically link to a national governance/legislative context, though many steps are guided by specific German procedures such as building regulations and financing schemes. Flöha was also able to make use of substantial urban development funds from State, federal and EU levels.

Flöha’s procedural aspects, strategies and experiences can be transferred, and serve as an inspiration for other towns and cities. It is necessary to amend the practice to the respective local situations, to address specific challenges and opportunities. A successful transfer of a project with such city-wide relevance requires long-term commitment by the city (decision-makers, stakeholders, citizens).

Though the practice has not been fully transferred, through the published results various aspects of the practice have found their way into strategies and practices of several cities in Germany already.