Placing Human Rights inside the URBACT method

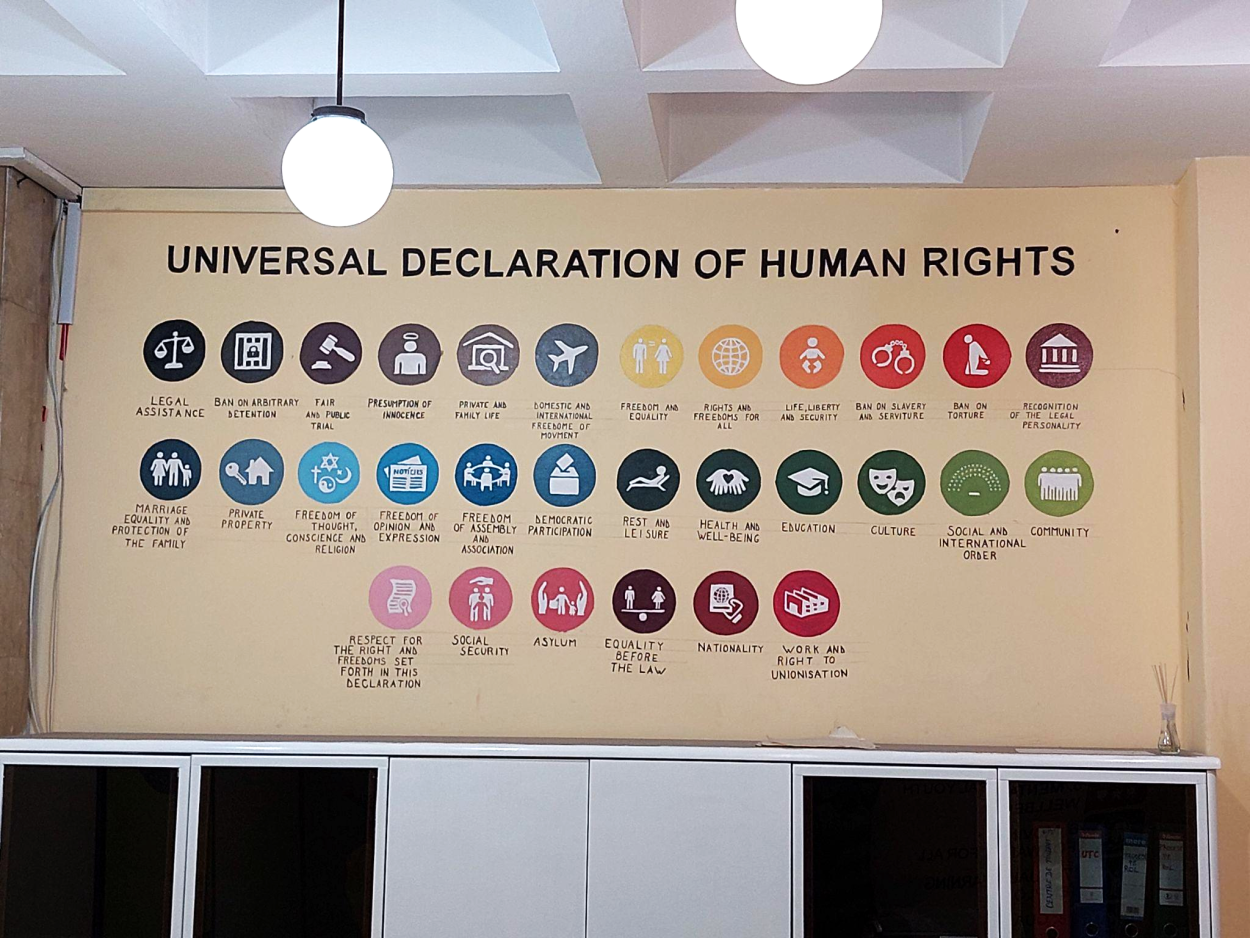

The Human Rights-Based Approach (HRBA) is a UN-framework to make human rights concrete. As WELDI partners learned in a masterclass, the HRBA starts by identifying human rights that are violated, the causes for this situation and the relevant stakeholders that have the power to change this situation. They include cities and states as duty bearers who have to protect human rights on their territory; the relevant stakeholder (think: employers, landlords, media) as “responsibility bearers” who also have to respect human rights in their work; and the rights holders themselves, in our case different categories of migrants, who are seen active agents and not just “beneficiaries” or “users”.

In designing actions to protect human rights, the HRBA puts a strong focus on the process being participatory and empowering and committing all responsible stakeholders. This approach resonates with URBACT principles, particularly the engagement of diverse stakeholders in policy design and implementation.

To orient their policies more closely to Human Rights, WELDI partners have focused on three thematic areas—work, housing, and healthcare—as well as cross-cutting activities to improve information and orientation for newcomers and their interaction with established residents.

Decent Work

Behind the apparent EU-consensus for curtailing migration, the shortage of workers in all strata of European labour markets has led to the emergence of temporary migration programmes for workers from Asian countries[1]. These recruitment programmes, facilitated by specialised agencies, often create dependency on employers and expose migrants to exploitation, while cities remain outside the deals and struggle to reach workers living under highly segregated conditions. Some WELDI partners are identifying representatives of these economic migrants to involve them in their work. At the same time, WELDI partners also focus on getting settled refugees and migrants into work, regardless of whether they have formal powers in employment.

WELDI’s network meeting in Fundão, in early 2024, showcased how cities can contribute to decent work on their territories. The Portuguese town works closely together with the national labour inspectorate and with employers to detect and prevent exploitation. One of the most inspiring initiatives that WELDI partners saw were the training courses that Fundão designed with local employers to prepare migrants in vulnerable situations for finding work in shortage sectors of the local economy.

Training to produce Fundao’s signature PDO Cheese and to manage olive orchards

Language skills are a key factor for pushing newcomers into working below their qualifications or in the informal sector. WELDI partners have found that the offer financed by the state falls short of the demand and does not cater enough for different learning profiles. Timisoara, for instance, works with a volunteer initiative to boost language learning and Sosnowiec is planning to provide Polish lessons for the most demanded vocational profiles. The initiative of the city of Utrecht to offer English language classes for newcomers and established residents inspired many, as it not only strengthens access to employment, but also creates a favourable situation for the interaction and reduction of stereotypes between newcomers and established residents.

Adequate Housing

Amid a Europe-wide affordable housing crisis, WELDI partners also struggle to provide adequate housing for both migrants and established residents. While municipalities cannot tackle the housing crisis alone, they can take meaningful steps to improve access. Fundão is leading by example, using EU recovery funds to expand social housing. Other WELDI cities, such as Liège and Albacete, have worked with the social rental agency model that temporarily leases vacant private apartments for vulnerable groups. This model has also been successful in Seine-Saint-Denis and the wider Paris region for housing refugees.

When WELDI partners discussed the reception of Ukrainian refugees at the network exchange in Albacete, they found that citizen-provided housing -e.g. in Poland, Romania, and the Czech Republic- have been a real innovation. This support model not only allowed cities to deal with huge numbers of arrivals, it also showed the way to de-segregating and de-institutionalising refugee accommodation. When public authorities provide a framework through matching platforms and quality checks, as happened in Timisoara, the experience of hosting Ukrainians can be an inspiration for the reception of other refugees.

Creating win-win-situations in improving access to health care

When meeting in Lampedusa, WELDI partners got first-hand experience of how EU policies over-determine local conditions - in this case, in the form of the arrival of more than 100,000 vulnerable migrants per year. Although the island has been mostly kept out of the management of arrivals by the Italian government, it has nevertheless been able to become part of a collaboration to respond to an increasing number of pregnant women arriving on its shores. Together with the Red Cross and regional and national authorities it enhanced obstetric and gynecological services which now also improve the lives of the local residents and the island’s 25,000 annual tourists, and at the same time reduce costs for emergency transfers to the mainland. Creating such win-win solutions is at the heart of the human rights perspective and can help shift public perceptions of migration as a burden.

One-Stop Shops, Digital Solutions, and City Cards

Effective information and service delivery are crucial for protecting human rights. Following a workshop that illustrated design-principles and real examples of One-Stop-Shops, several WELDI cities are exploring how to implement this idea, which streamlines access to city services for migrants and enhances inter-agency collaboration. Sosnowiec, Cluj-Napoca, and Liège are in the process of setting up new one-stop-shops or expanding existing facilities. However, securing funding and political support remains a challenge.

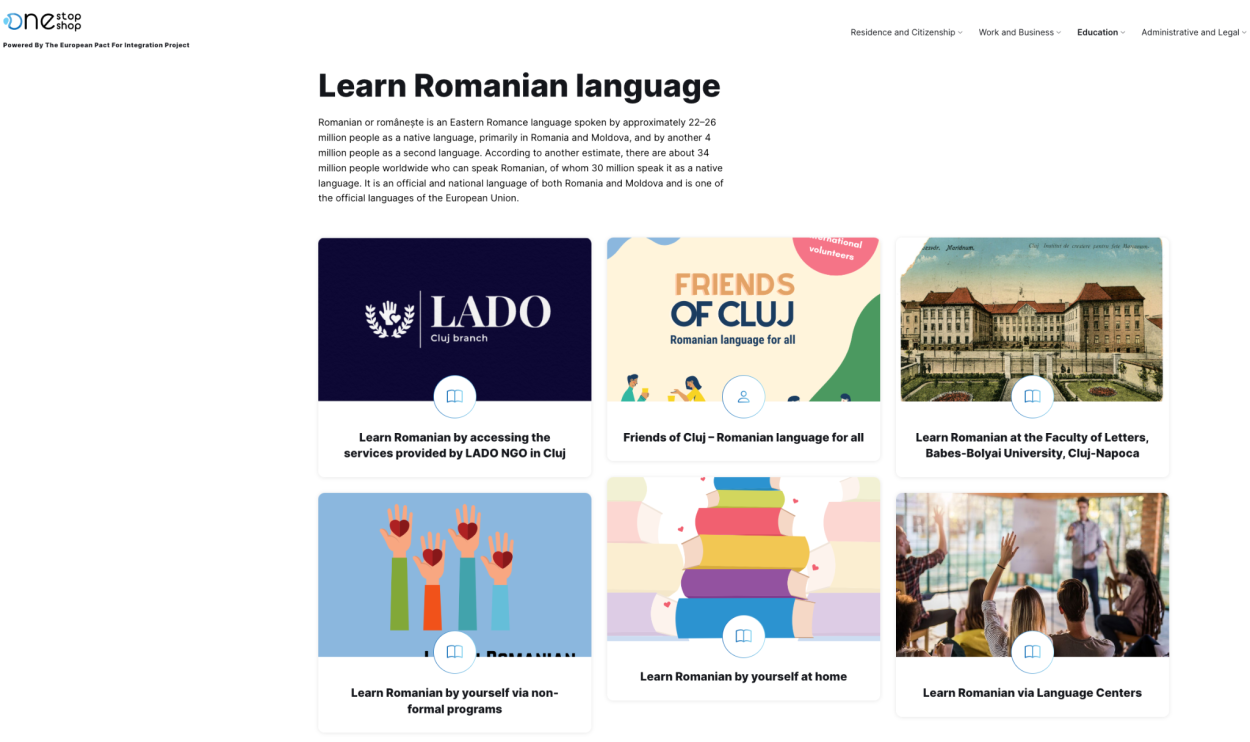

To complement physical service hubs, WELDI partners are also exploring digital tools. When the City of Cluj presented its website “Welcome to Cluj” at a workshop on digital guidance, the fellow-Romanian WELDI partner of Timisoara got inspired to develop a similar resource, which is still missing in the city.

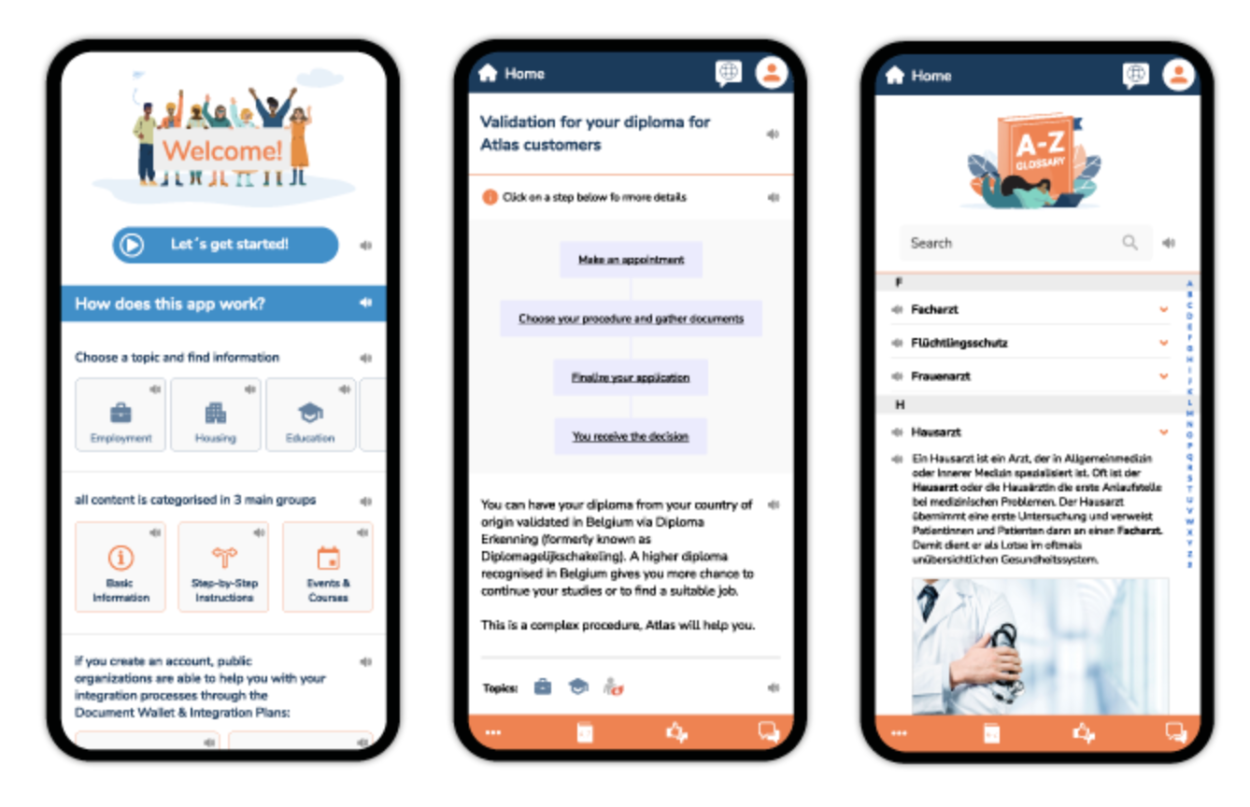

WELDI is also collaborating with MICADO, a Horizon2020-funded project that developed a multilingual guidance app for migrants, to assess how this pilot app could be tested by WELDI partners to improve guidance for newcomers.

“Welcome to Cluj” website and MICADO guidance app for migrants

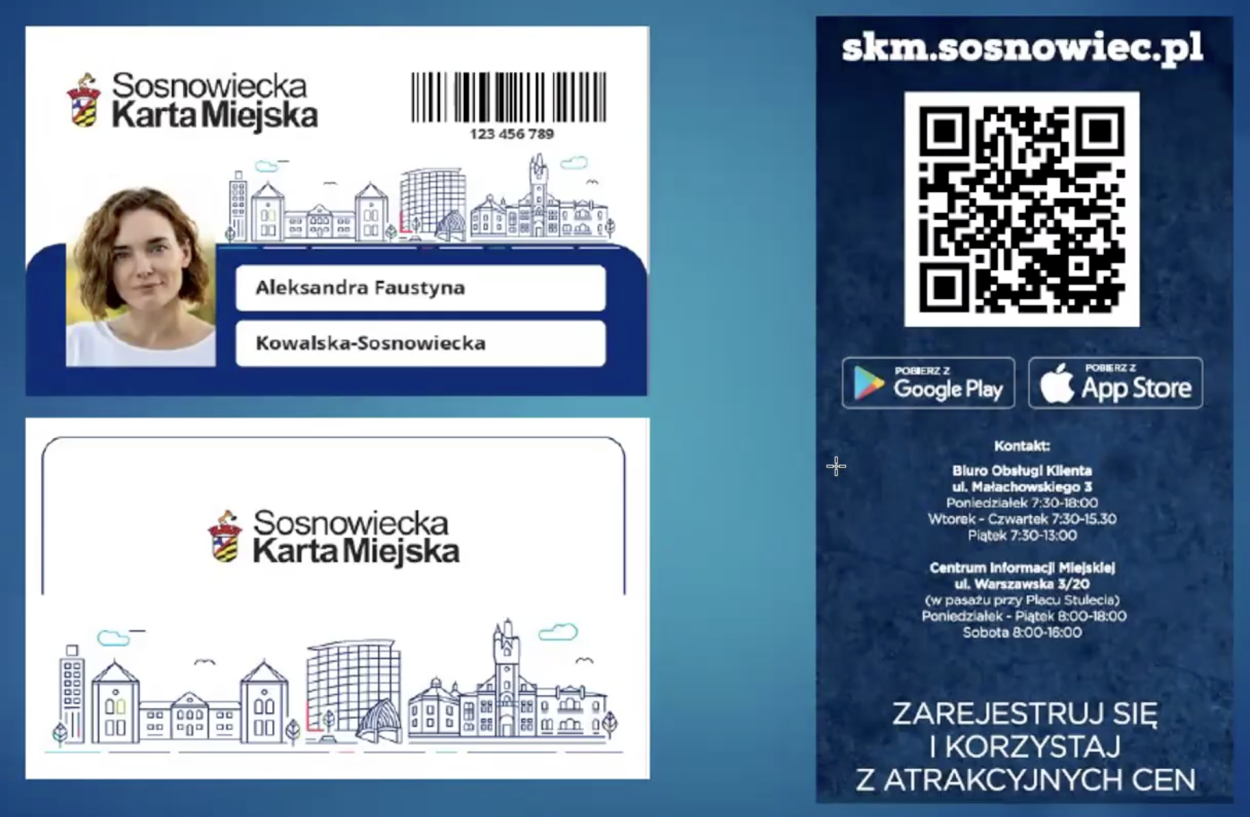

City cards are another promising tool for expanding access to local services, particularly for residents with precarious status. Four WELDI partners are integrating city cards into their action plans, following in the footsteps of other European cities such as Zurich, Bern, Berlin, Hamburg, and Lyon. After a first bilateral exchange took place between Utrecht and Liège to learn more about the practicalities of city cards, Liège organised a workshop dedicated to this topic at the end of 2024.

Liège’s Carte Ardente is already well on its way, with broad stakeholder support and migrants with a precarious status agreeing on the card’s potential for improving access to rights. Meanwhile, Sosnowiec’s city card, introduced in 2022, offers discounts for sports and cultural events but has low uptake among migrants. The city aims to increase participation to foster a stronger sense of belonging and interaction with long-term residents. Utrecht is considering a city card specifically designed to support residents without legal status by gradually integrating relevant municipal services.

WELDI partners learned during the workshop that digitalisation and smart city initiatives can be a catalyst for improving the situation of residents with a precarious status, if they are designed in an inclusive way. They also saw that city cards are long-term projects that need broad coalitions, including with civil society, to thrive.

Liège’s Carte Ardents (prototype) and Sosnowiec’s city card

Teaming up with Civil Society and Migrant Residents to Fight Prejudice

Beyond these hands-on tools, WELDI cities are working on how to combat hate speech and anti-migrant prejudice. They cannot ignore that a strong mobilisation is needed to counter extremist parties using professional trolls and technology to spread hateful messages and lies that violate human rights and undermine social cohesion.

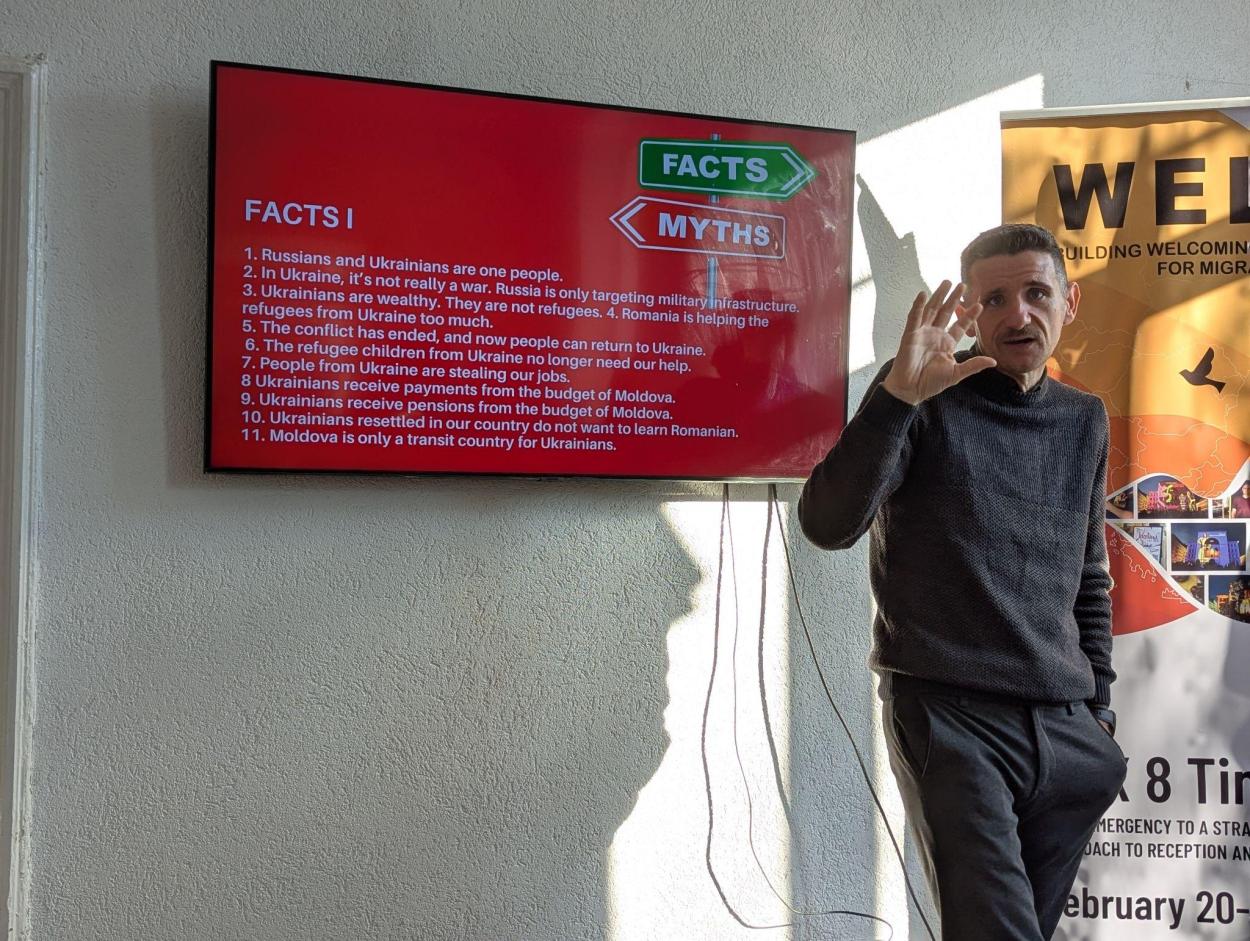

The network meeting in Timisoara, three years after the outbreak of the Russian attack on Ukraine, showed that partnership with civil society is essential to prevail against the attack on our rights-based system.

Timisoara-based association LOGS presenting their project against anti-migrant myths

Timisoara also illustrated another of WELDI’s key learning points from the past 18 months: that efforts in protecting human rights have to build on migrants as protagonists and draw on the resources of migrant communities whenever possible. This implies consulting migrants and refugees, as the city of Sosnowiec did in a large-scale survey, drawing on their ideas and initiatives, and having migrants represented in URBACT local groups.

WELDI, in its first 18 months, has demonstrated how local commitment, solidarity and creativity can make a difference in a difficult environment.

[1] In 2023, Poland issued more than 37,000 first-time residence and work permits for citizens from Central and Southern Asia and the Philippines; Croatia issued 23.736 permits for the same group of countries, Hungary 15,179 and Romania 9,798 (source: eurostat migr_resocc).