“Making public spaces safer” is the common goal for the cities of Manresa, Liepaja, Geel, and Naples that are part of the CITISENSE project. Following the lead of Piraeus and the BSFS project, these cities have gathered to reflect on how to replicate aspects of the project, such as governance, digital tools, and social and spatial interventions.

From the 19th century utopians to today’s citymakers, the idea that we can impact human conduct through clever spatial transformations is very seductive. Public spaces are eloquent. They tell us stories. And when it comes to security, public spaces are both a product and a producer of insecurity. City dwellers take cues from their environment that affect the way they use it and perceive it.

But before we can rush to AutoCAD and plot the next revolutionary public space, we need to properly diagnose the problem. From broken windows theory to target hardening and CPTED, approaches for security and design abound (not without criticism). However, if the diagnosis part is lacking, security issues can be made even worse. Especially if neither the diagnosis nor the solution takes into account socio-spatial inequality, systemic violence or insights from vulnerable groups.

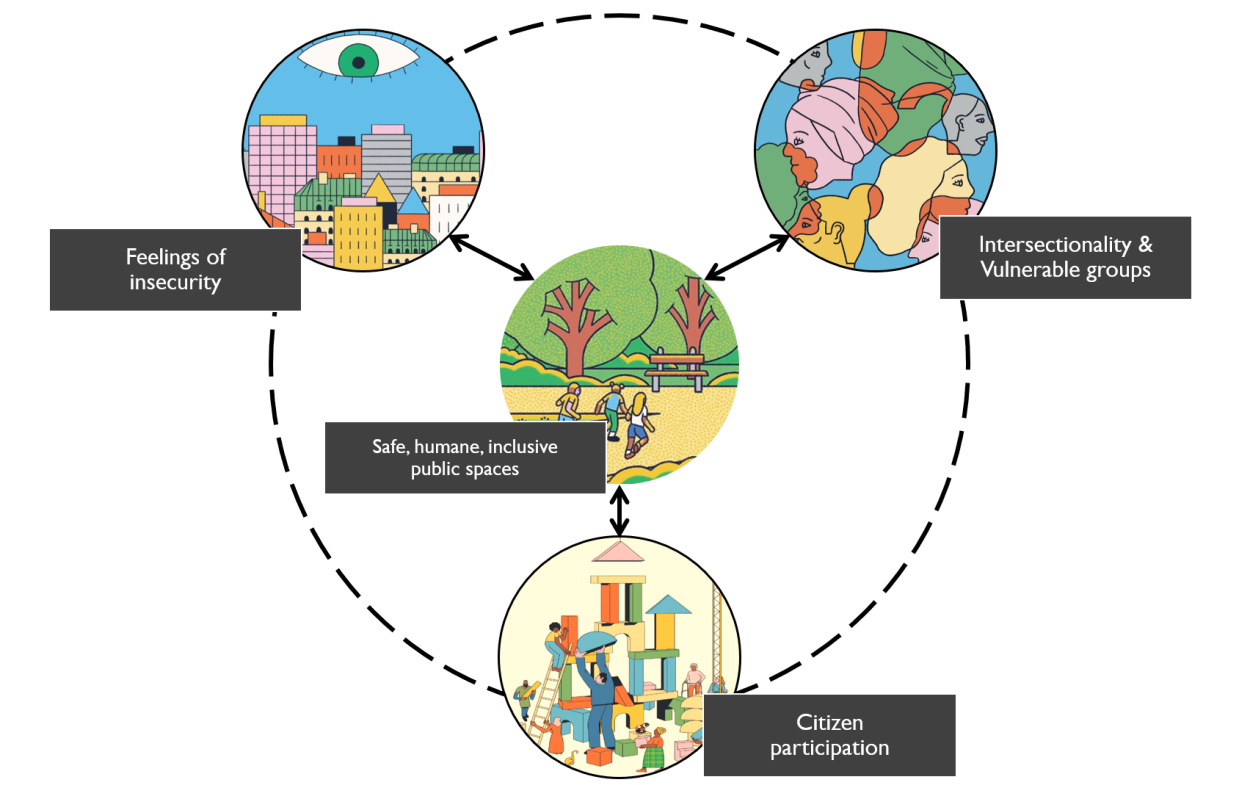

Recently, I had the pleasure of sharing with city representatives involved in the CITISENSE project the SHIp Method to diagnose (and intervene) public spaces. The goal of this method is to place vulnerable groups –those that have traditionally been excluded from discourse around security- at the center of actions towards safer public spaces.

Here are 3 key concepts of this approach:

Concept #1: “Feelings of insecurity” is different from “fear of crime”

It is easy to confound “fear of crime” and “feelings of insecurity”.

Fear can be a feeling, and crime can be one trigger for insecurity. A low level of crime does not necessarily imply a positive perception of safety, and even less so for the most vulnerable populations.

Feelings of insecurity go beyond fear: normalization and minimization is also a strategy to cope with violence, particularly among groups that are not taken seriously by authorities due to discrimination or stigmatization.

Insecurity goes beyond crime. It can also be microaggressions, everyday violences (yes, plural), and incivilities that are not going to be necessarily handled by law enforcement.

Feelings of insecurity are influenced by environmental characteristics, socio-demographic variables and social representations of places deemed dangerous, among others, and these perceptions have the power to affect physical and social mobility while modifying the geography of the city.

Concept #2: Intersectionality and vulnerability

Intersectionality refers to the multiple forms of discrimination and oppression that combine and reinforce each other, affecting marginalized groups particularly. This includes racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, transphobia, etc. For example, women’s concerns are generally dismissed as exaggerations, but a wealthy woman and a poor woman are going to be also treated differently because of their socio-economic status. These interactions of layers define vulnerability.

Vulnerable groups are touched first and most by phenomena of violence. And frequently, the violence that they face is normalized by dominant groups as a way to dismiss them, and minimized by those who experience it as a way to cope. Vulnerable groups are oftentimes counted out, blamed for their problems or even criminalized.

Not everyone is equally empowered to raise their voices about issues of insecurity and be heard. Oftentimes, the strongest opinions about unsafe public spaces come from people who don’t even live in them. As city makers we need to take this into account, and question who gets to define a space as dangerous.

Concept #3: Citizen participation and public space transformations

Participatory processes involve the public in solutions to urban problems, from the base of informing them about what is going to happen to more complex actions of collaboration and decision-making.

Citizen participation to address crime and violence can be used to diagnose the problem, co-create solutions to the problem, evaluate and give feedback on the proposed solutions.

Plenty of actions aim to include city dwellers in various degrees. However, city makers oftentimes forget to consider who is being empowered to participate in these processes. City dwellers involved in collective action are less likely to come from poor, crime-ridden, and/or marginalized communities. This is not because they are intrinsically unable or uninterested to do so, but because they face pressures from a wider social structure: poverty, discrimination, precarious work conditions. Oftentimes, these marginalized communities are already burnt out from being constantly ignored (or even criminalized) by authorities and have little trust on initiatives. And in some cases, getting involved in participatory actions can even put them in danger in their communities.

Paradoxically, these are the communities that would benefit the most from an inclusive and participatory approach. City makers need to consider who is missing and why.

What can citymakers do?

A correct diagnosis of the problem is essential to propose an adequate solution. As citymakers, we may want to solve social issues with spatial measures. While they contribute in no small measure, they can only be a part of the solution that needs long-term interdisciplinary involvement and political backing.

We must keep in mind while trying to solve issues of insecurity that knowing our users and involving them at different stages of the process is key. However, just getting people involved is not enough. We must consider whose voices are missing, whose concerns are being treated as exaggerations and why. City makers have technical expertise, but the city dweller has the empirical expertise about how they use and live public spaces.

You can consult the SHIp Initiative booklet here

Further reading:

International Association for Public Participation. Pillars of Public Participation.

UNESCO. (2020). Inclusion Through Access to Public Space.

UN HABITAT. (2010) A safe city is a just city.