WELDI - Building welcoming communities for migrants

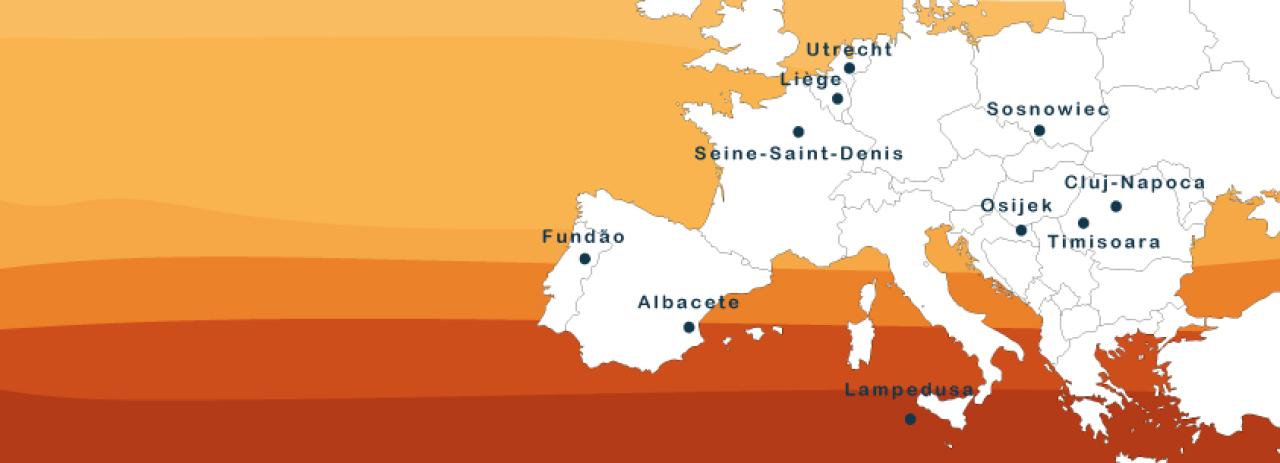

Through the URBACT network WELDI, ten local authorities from across Europe want to become more welcoming places for newcomers. Here is where they are 6 months into the project - a period packed with setting up local stakeholder groups and having first discussions about how to make this goal a reality.

WEDLI’s starting point is the right of cities to take care of the rights of all their residents. Under this universal claim, WELDI focuses on migrants and the particular obstacles they face –lack of residency papers, for instance, discrimination or language acquisition – obstacles which cities can help them overcome. WELDI partners embrace this idea in labelling themselves as City of Human Rights (Utrecht), Welcoming Cities and Territories (Liège, Fundão, Seine-Saint-Denis) or as City of Equality and Respect for Diversity (Sosnowiec) and spelling out these aspirations in council motions, local coalitions and transnational networks.

The ten partner cities have different migration histories and contexts, which are reflected in their different priorities. This first phase of WELDI showed that across Europe, migrant categories are not used in a similar manner and can have different connotations in different places. WELDI partners are aware that they stem from a state-centred perspective on human mobility and that they need to be overcome in the pursuit of a human rights based approach. Yet for the time being, cities cannot completely ignore these categories either, as they often set the framework for local action.

Human rights versus residency papers

Undocumented migrants are the most vulnerable group when it comes to access to rights. WELDI partners such as Utrecht, Liège and Seine-Saint-Denis are fighting to make human rights independent of papers, and have found ways to provide access to shelter and basic healthcare, for instance. But granting such rights is often precarious. One way to put them onto a more solid basis are physical or digital city ID cards that Liège, Utrecht and Cluj want to pursue in their action plans. They can be a powerful tool to facilitate access to rights and services for all and to forge a common local identity.

Learning the lessons from Ukrainian refugee reception

Refugees from Ukraine are a key group in most WELDI cities. For some of these cities, such as Timișoara, Cluj, Sosnowiec and Osijek, they constitute the first major arrival of newcomers in recent times. Now that this influx been managed through an unseen mobilisation of civil society and local government, the issue is to prepare the next steps, which means switching from an emergency mode to a sustainable strategy, and ensuring access to housing, education and work that can last for as long as needed. The fact that Ukrainians can freely move across the EU makes it challenging to understand how many there are in each city, and the ongoing war makes it difficult for both refugees and city councils to plan ahead. Against the widespread criticism of a privileged treatment of Ukrainians in comparison to other refugees, WELDI partners want to learn from the experience of the Ukrainian reception model how to improve the reception of all refugees. The positive effects of fast access to rights and more decentralised reception models can be a part of these lessons.

Sosnowiec and Osijek, they constitute the first major arrival of newcomers in recent times. Now that this influx been managed through an unseen mobilisation of civil society and local government, the issue is to prepare the next steps, which means switching from an emergency mode to a sustainable strategy, and ensuring access to housing, education and work that can last for as long as needed. The fact that Ukrainians can freely move across the EU makes it challenging to understand how many there are in each city, and the ongoing war makes it difficult for both refugees and city councils to plan ahead. Against the widespread criticism of a privileged treatment of Ukrainians in comparison to other refugees, WELDI partners want to learn from the experience of the Ukrainian reception model how to improve the reception of all refugees. The positive effects of fast access to rights and more decentralised reception models can be a part of these lessons.

Bottom-up change in the reception of asylum seekers

At a moment where asylum applications in the EU are at a record high since 2015/16, asylum seekers and Geneva Convention refugees are another important group for WELDI partners. Asylum is a national competence in most EU countries, depriving local authorities of any role in accommodation and support. WELDI partner Lampedusa is an extreme case in this regard, as it has to bear the brunt of the failures of EU migration policies like few other places: in 2023 alone, the tiny Island has been the “gate to Europe” for almost 150,000 migrants landing with small boats from Tunisia and Libya. While previously the local level was involved in the reception, this role has been monopolised by the central state in the frame of its “securisation” policy. Newcomers stay for a maximum of three days on the island’s “hotspot” after which they are transferred to Sicily or the Italian mainland. Having thus become a mere place of transit for asylum seekers, and of migrant deaths, Lampedusa wants to reclaim agency, starting with improving services on the island that help both arriving migrants and the established population, together with the region and the state.

Utrecht’s Plan Einstein pilot is a pioneering initiative in claiming a role for cities in the design and location of asylum seeker accommodation. This new model wants to punch holes into closed-off accommodation centres and provide services that make asylum seekers interact with neighbourhood residents. In Liège, the federal reception agency Fedasil is willing to engage with the city in a local one-stop-shop, while Fundão is cooperating with the Portuguese High Commissariat for Migrations in hosting humanitarian refugees and victims of human trafficking in its city-run migration centre.

The plight of economic migrants

Economic migrants are one of the groups whose struggle for rights perhaps receives less public attention (there is a vivid debate at EU level) WELDI partners like Osijek or Cluj report of people from Asia and Africa who arrive through migration organised between commercial mobility managers and employers to work in industry and services. Living in accommodation provided by companies, the workers are often off the radar, out of local services’ reach and prone to social isolation and exploitative work and life situations - a return of guest worker policies. In a variation of this scenario in Albacete’s agricultural environment, migrant workers are locked in an exploitative system where middlemen operate in parallel to public services, provide jobs, accommodation and many other services.

Coordination and guidance

Migrant reception and integration support is a complex issue that involves many actors. It affects and is affected by health, housing, education and employment policies. It is not surprising, then, that many of the obstacles migrants face in WELDI partner cities are about governance and coordination. National governments can negatively impact local action: by actively undermining inclusion, as did the previous Polish government, or by causing, through passivity, legal vacuums and policy gaps. Costly and bureaucratic procedures for the recognition of foreign qualification is just one example of a challenge that many migrants face. National government is too important to be ignored, and WELDI cities try to engage national representatives, starting with their local stakeholder groups.

In addition to coordination across administration, relationships to civil society are a key factor for making cities more inclusive. In some of the WELDI cities, such as Liège, Seine-Saint-Denis, Osijek or Albacete, the active role of civil society is very clear, while in others it is less present. Sometimes, the support offer from NGOs and public bodies is too complex to be easily navigated by newcomers, and seemingly boring topics such as locally-led coordination can make a real difference. One-stop-shops which unite different services under one roof are one of the solutions that WELDI cities such as Liège, Albacete, Cluj-Napoca, Seine-Saint-Denis and Timisoara will explore in this project.

Migrants as protagonists

The success of many policies and services in cities also depends on whether or not they are grounded in a solid analysis of their “target group”. While consultation mechanisms and bodies exist in many WELDI cities, real co-creation that systematically involves migrants as experts by experience in policy design is still rare. In cities that are new arrival destinations, co-creation holds a particularly great potential to get information in a situation where it is scarce and where little experience exists. Working with migrants helps to change from a relationship based on seeing migrants as passive “beneficiaries” to empowerment and protagonism. To support such efforts, WELDI partners are planning to initiate a multi-local “community researcher” group to inform the project.

All these different challenges and possible solutions converge in a vision that the reality of migration cannot be captured in concepts and policies that presuppose integration into static national societies. WELDI wants to contribute to a new local reception model that is centred on the people - those arriving and those who are already there - and makes the most out of human mobility for all.