Author: Béla Kézy, Lead Expert of ThrivingSTREETS

The article presenting the Thriving Streets URBACT Action Planning Network, and its ambitions was published on 2020 February 5 on the URBACT website. It reflected optimism, dedication, and commitment of all partners to address the challenge at hand: reducing car-dependency in their cities, making them “more healthy, attractive, accessible, inclusive and thriving places”. It quickly turned out, though, that our plan was like those proverbial battle plans that did not survive the first encounter with the enemy.

Roadblock ahead: the Covid pandemic

Literally weeks from the publishing of the article, the COVID19 pandemic hit hard and changed everything. As a result of the pandemic, after a normal Phase 1, Thriving Streets APN abruptly faced a situation unseen before: international travel was out of question, any activities requiring people gathering and doing things together became impossible – while all local authorities were suddenly flooded with a multitude of new, pressing, and urgent challenges.

These new circumstances made applying even the core URBACT principles extremely difficult for every actor involved – especially for the partner cities. The network as a whole and local teams faced various hard problems:

● How can you share knowledge and learn from other European cities (your partners) when you cannot meet physically and the only way to learn about practices is to watch videos and listen to online presentations?

● How can you use a participative approach and engage local stakeholders, have a human dialogue, work together, and co-create when you are not allowed to meet and be in the same physical space?

● How can you motivate your local decision-makers, politicians, and even your colleagues at the Mayor’s Office to be part of a forward-looking thinking, planning and co-creation process when they face hundreds of new problems requiring their immediate attention?

On top of all that, Thriving Streets partners work on place-based challenges - problems, issues linked to streets and other public spaces in the city. When it comes to properly understanding such challenges, - and the solutions, practices addressing them - online presentations, even sophisticated video-walkthroughs cannot replace simply walking in the area, seeing with your own eyes, entering into conversations with people and sensing street life unfolding.

Along their journey, partners have faced unexpected obstacles, did their best to overcome them, tried hard and often failed. One of them even gave up and decided to leave the network. The rest of them, however, kept trying. When one thing did not work out, they got creative and tried something new, while sharing their experience with each other. Looking back, we can now safely say that despite all the challenges, and somewhat miraculously, Thriving Streets partners managed to keep it together, function as a network, help each other, work hard and find alternative solutions. As a result, today they are all on the right track towards meeting the objectives they set out at the beginning of the project.

What did we learn?

Being part of an URBACT network is always a very intense learning journey - even in “normal” circumstances. As we’ve seen, though, so far, circumstances have been anything but normal. Therefore, while partners have learned a lot about the URBACT method of integrated and participative planning, they were also forced to move fast, be agile and creative in addressing problems, and along the way they gained lots of useful knowledge and skills.

Probably the biggest hurdle every partner faced was engaging and collaborating with local stakeholders due to the various pandemic-related restrictions. That led partners to experiment with alternative ways – like for instance having one2one meetings and individual phone discussions (like Debrecen did), using Google maps to jointly work online on a specific street or neighbourhood (which Parma found a useful approach), or going door-to-door of small shops in a specific street section and have informal chat with shop-owners and customers. Granted, none of these are new and revolutionary tools – but partners would probably not have used them under “normal” conditions. While not replacing traditional ULG meetings, these for sure will become part of their participative planning toolkit.

Partners have also learnt that online meetings sometimes can be viable alternatives to in-person meetings. The pandemic forced the network to move in the online space from one moment to the other. Transnational meetings were redesigned to be held online, and slowly everyone understood that it is perfectly possible to meet and work with your counterparts online, if necessary. Partners quickly realized that – while you cannot simply replace all physical meetings with online workshops – sometimes it is not necessary to travel long distances just to have a short training session or technical discussion. It is clear now for everyone that combining a small number of in-person meetings with regular short online sessions will be part of the new normal - not only transnationally, but also on local level. Besides, it can save massive time – not to mention its environmental benefits.

These changes have also pushed partners to quickly become proficient in working in an online setting. This required learning the use of online meeting solutions, visual collaboration tools, file sharing applications - as well as how to communicate in an online setting, etc. The process was (still is) the typical example of learning-by-doing, trial and error – forced by external circumstances. Nonetheless, by now all partners feel convenient when there’s a need to work online.

Small-scale actions: what is success?

The concept of the SSA has been quickly understood and welcome by partners – they all found it a great way to test and refine some of the interventions. However, it seems that the pandemic has also affected (and not in a good way) the implementation of the small-scale actions. While some partners managed to complete their small-scale actions, due to the restrictions, some others decided to postpone their SSA to early 2022.

Antwerp (Belgium) and Nova Gorica (Slovenia) have already completed their small-scale actions - they both implemented temporary interventions in public space - with different outcomes and learnings.

The Antwerp local team delivered a temporary intervention in the Deurne neighbourhood of the city. Deurne has 80.000 inhabitants and is located between the historic city centre and the Wijnegem Shopping Center, in the proximity of the 20th century belt. Deurne is dominated by wide roads and misses a clear district centre today. Most of the streets – including Frank Craeybeckxlaan, where the temporary intervention took place - are designed to facilitate rapid, unobstructed flow of car traffic. The goal of the temporary intervention – implemented between November 2020 and August 2021 - has been to experiment with road diet and traffic calming on a small section of the street while also creating a more pedestrian-friendly space. The temporary intervention was a failure in the traditional sense – led to a protest of shop-owners and in the end the district decided to remove it and restore the original status. However, it still provided valuable lessons for the planned long-term redesign of the street:

● It clearly demonstrated that creating a public space does not mean that people will automatically start to use it.

● More active involvement of residents already in the design phase of the temporary intervention would have been important.

● Despite being considered as a failure in the traditional sense, it still facilitated an intense dialogue wouldn’t have taken place otherwise and taught important lessons about the real needs and expectations of the residents.

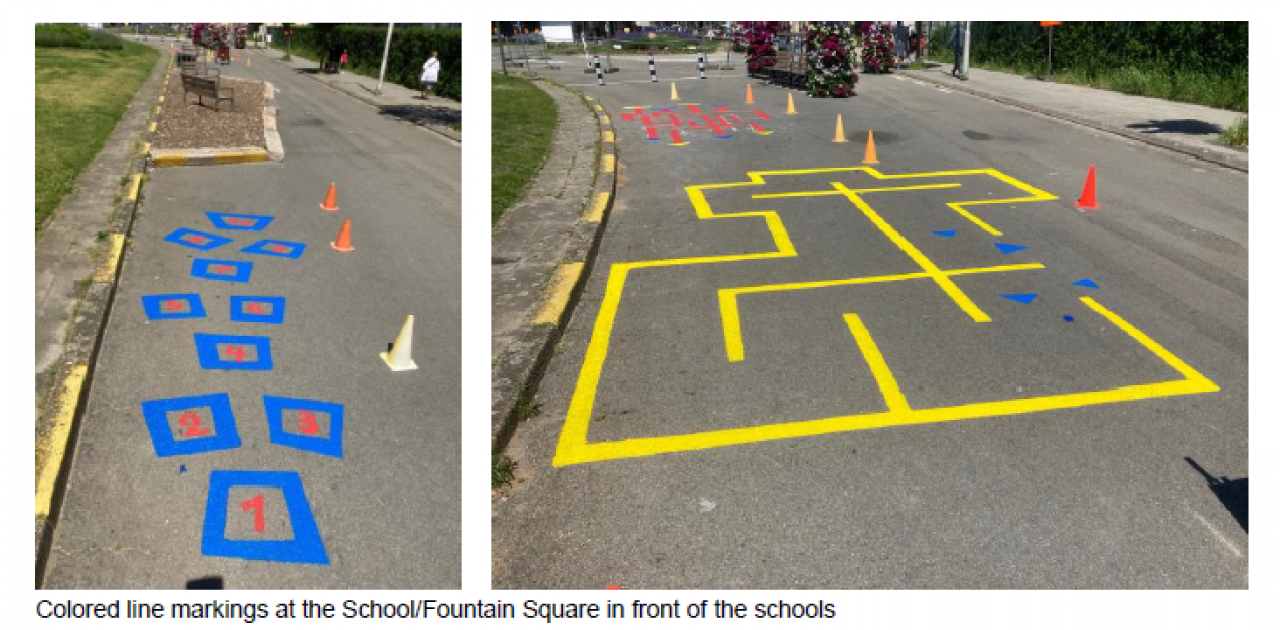

Nova Gorica has also implemented a temporary intervention - albeit a quite different one. The Integrated Action Plan of the city focuses on the historic district, Solkan, with the objective of reviving the area. Solkan had been an independent, lively town for centuries; today it is a degraded area with poor services, where cars occupy most of the public spaces. The vision for Solkan is to turn the neighbourhood into “a lively old town with people, bars and shops, which will also be attractive for tourists and can be safely crossed by an 8-year-old child”. To prepare for the transformation the Nova Gorica team has implemented a temporary intervention in the Solkan area to facilitate dialogue with the residents to better understand the challenges and needs in the area.

The temporary intervention focused on one of the central squares of Solkan old town, and involved:

● The repositioning some parking places to free some space for other activities.

● The placement of a small “kiosk” on the square, which hosted a range of services (street food, drinks, workshops, and various events) during the experiment.

Despite the occasional criticism, negative comments and complaints, the temporary intervention was successful. It helped the local team to have a much better understanding of the area. Even though they made great efforts of involving the public already in the process of creating a vision and designing the campaign, they were able to gain a much broader response and detailed insight into the issue of space only when they tried to realize the vision with concrete actions on the spot. These insights will help the process of reviving the area.

At the end of the experiment the kiosk has been disassembled and stored but will definitely be used in other parts of the city as the “heart” of temporary interventions aimed at encouraging participation.

The examples of Antwerp and Nova Gorica show that when it comes to temporary interventions, success is a relative term. Temporary interventions are tangible changes that can induce meaningful dialogue with people: it is easier for them to express their opinion and feelings regarding something they can see, “touch and feel”, than talking about concepts and plans presented on paper. Even if a temporary intervention is not liked by people - but helps to better understand their real needs and expectations - it can be considered successful, as it helps to avoid costly and unchangeable mistakes.

What’s ahead of us?

Although currently the pandemic still seems to linger on, unfortunately, we are still hopeful that in the last months until the end of the project Thriving Streets partners will have the opportunity to deliver more in-person meetings both locally and on transnational level. It would be crucial to have real human dialogues and positive experiences to reignite motivations.

To that end, we are planning for a couple of in-person transnational meetings, visiting partner cities, working with them as a team on local challenges and sharing knowledge and experience between partners. Besides, these visits could contribute to strengthening bonds, informal relations, laying the foundations of future cooperation.

We also know that, although online learning events were useful to gain thematic knowledge, the best way to learn about space-related challenges and their possible solutions is to experience them with our own eyes and feet. Therefore, we also plan to organize a study tour to a city that is in the frontline of creating thriving streets. Such a visit could provide knowledge, and, most importantly inspiration for partners. If some politicians could be persuaded to join, it may even contribute to regaining their support to the local initiatives.

We now know that the last period will not be any easier than the past almost two years. Having said that, we are also convinced that all Thriving Streets cities individually, and the partnership as a whole are resilient enough to overcome difficulties and come up with action plans that will make an important contribution towards turning their streets into “more healthy, attractive, accessible, inclusive and thriving places”.