What has crowdfunding got to do with urban development? What part of the future funding mix could crowdfunding play for European cities strapped for cash yet needing to respond to change and deliver sustainability?

These were some of the questions addressed by the URBACT ESIMeC II network in a masterclass on innovative financing which explored a range of different models - financial instruments, social investment bonds, public-private-partnerships and (the focus of this article) crowdfunding[1].

Why are URBACT cities starting to consider these different approaches?

ESIMeC cities, like many others, found that as they embarked upon the delivery of their Local Action Plans, one of the common challenges they faced was securing resources. The timing was poor as LAPs were completed just as many of the 2007-2013 Structural Fund Programmes were coming to an end and before the 2014-2020 Structural and Investment Fund Strategies had been developed. Some cities were confident that some of the actions in their plans would ultimately be funded through the future programmes. Others were of the view that, in reality, these programmes were only part of the solution. They acknowledged that the traditional grants culture was changing and wanted to understand some of the new financing mechanisms which are being developed and introduced. Sustained austerity within public finances means that cities need to think differently about how to fund their activities. This is in part driven by a need to do more with less but is also in recognition of the fact that a grants culture can create dependency whereas other more innovative financing methods may lead to greater and more sustainable impact.

Linked to this, cities want to be able to develop longer term approaches to sustainable urban development and short term projects, reliant on grants from external bodies, often lack the coherence required to deliver long term strategies like those included in URBACT LAPs. The situation is mirrored at an EU level with Financial Instruments being a key feature of the new Cohesion Policy programmes for 2014-2020 (see CSI Europe results). Clearly cities will not be replacing their current funding strategies completely. Rather they are starting to look at new and different ways of funding their programmes which complement and add value to the more traditional methods.

"Looking at the socio-economic impact, it has been interesting to observe how the organisations that have used alternative finance have generally performed well after fundraising, with the majority of them reporting increases in employment, volunteering, turnover or profit" (Understanding Alternative Finance', NESTA and University of Cambridge, 2014).

So, what is crowdfunding?

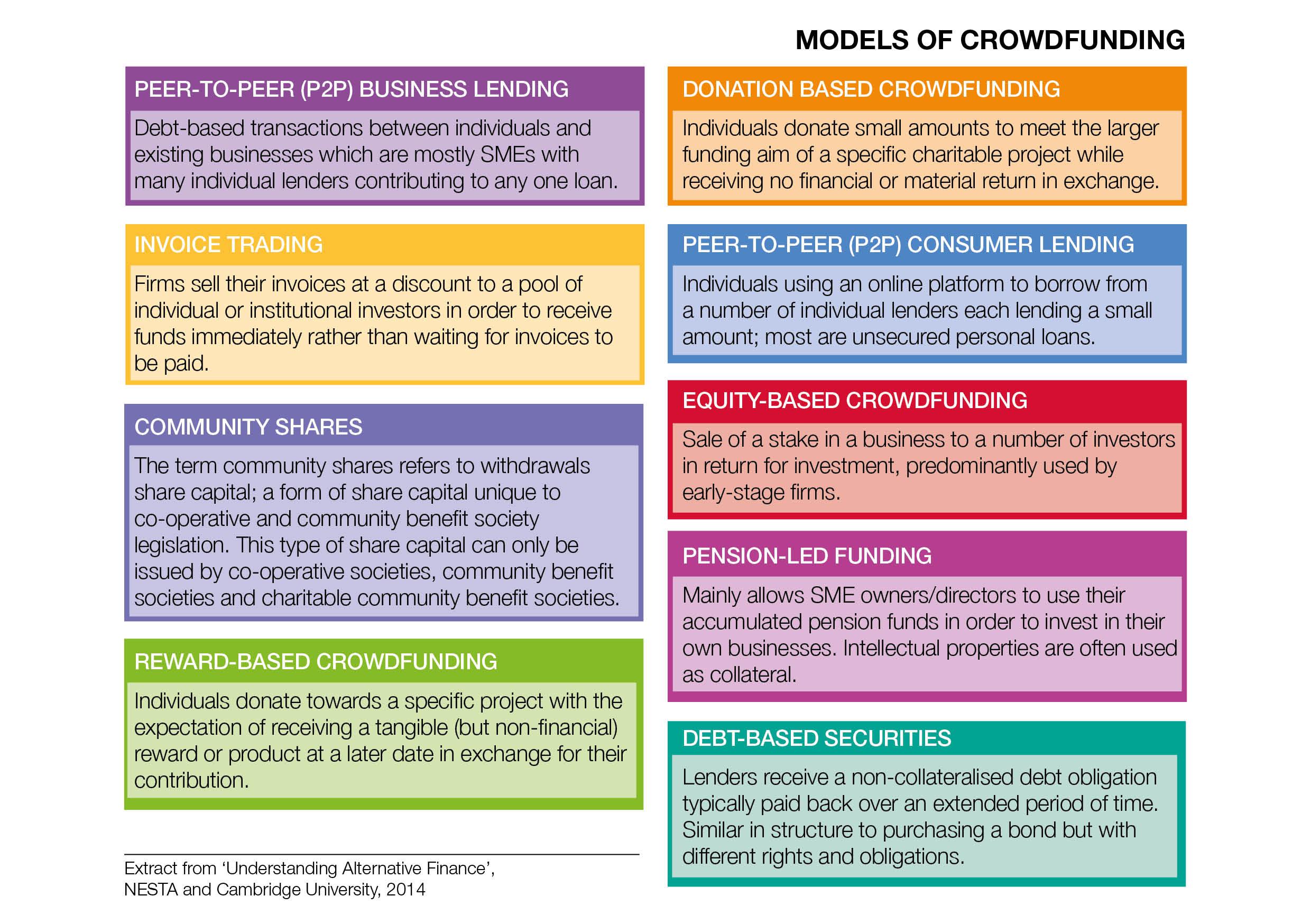

Crowdfunding is where a project is financed by raising funds from a large number of people, typically via the internet. There are 3 main types of crowdfunding:

- Equity based crowdfunding - the sale of a stake in a business to a number of investors in return for investment

- Loan or debt based crowdfunding - funds are borrowed from lots of people online rather than from a bank

- Rewards based crowdfunding - Individuals donate towards a specific project with the expectation of receiving a tangible (non–financial) reward or product at a later date in exchange for their contribution

As well as raising funds, this approach is seen as helping to validate an idea or project and generate enthusiasm amongst the 'crowd' creating valuable advocates and project champions.

....and what does that mean for cities?

There are perhaps three main areas of potential for cities.

First of all, crowdfunding has potential to unlock access to finance barriers for young businesses and start ups, thereby helping cities to grow jobs and increase competitiveness. This is one of the biggest challenges facing start ups today. Traditionally, financing a business or project involved raising large sums from a small group of investors. Crowdfunding has revolutionised this approach, harnessing the power of community and the internet to enable SMEs and entrepreneurs to showcase their businesses and projects to a vast pool of potential funders.

A good example is in Westminster[2], London where a crowdfunding accelerator 'Raise Impact', a was piloted by Impact Hub Westminster[3] during spring 2015. The pilot brought emerging entrepreneurs and start ups together with a whole range of crowdfunding experts (from Cambridge University, Ben & Jerry’s, Buzzbnk, the UK Crowdfunding Association and others) who delivered workshops on topics such as the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS), rewards crowdfunding and marketing. The programme developed participants’ understanding about the crowdfunding campaign model and lifecycle, on key areas including the offer, the execution and life post-campaign. Campaign-ready SMEs then received one-to-one expert support in essential areas such as video production and business mentoring. This is a great example of how to use structural fund programmes to support a city's job creation and competitiveness goals by helping start-ups access much needed finance through crowdfunding.

“Raise Impact presents a unique opportunity for participants to gain access to the top talent in the UK crowdfunding sector, to ensure they are prepared for success.” Julia Groves, Director, UK Crowdfunding Association

“(Raise Impact) has been really useful for us to guide our current work, realign and realise what we are going to need to do. I was really happy to get on this course because I know it was really competitive, and I’ve found it extremely useful - it might be the difference between success and failure in our campaign.” Andrew Campbell, Massive Small Compendium[4]

Secondly, crowdfunding helps communities to come together to invest in their own spaces and places and / or to improve the environment where they live. This is often called civic crowdfunding. Good examples include:

- The Luchtsingel complex in Rotterdam - a 'crowdfunded bridge' including a rooftop vegetable garden has been developed to connect a deprived neighbourhood to the city centre. Crowdfunders could fund a section of the bridge, and could customise their section - or even just a plank - with a name, a wish or a message to the city.

- Memphis Bioworks in the United States which is in the process of using the crowdfunding website In Our Back Yard (IOBY) to raise money for Memphis Civic Solar, a project that aims to install 1.5 megawatts of solar energy capability across 30 different municipal buildings across the city.

At a much smaller, more local scale crowdfunding is increasingly used by communities to develop their parks and gardens. There is also a wealth of community crowdfunding projects which seek to fund community events be they cultural, educational or just plain fun!

Civic crowdfunding is also used to facilitate bottom-up initiatives by connecting them to local government. An example is Brickstarter, which seeks to address the fact that just raising the money to build something in a city isn't enough: you have to get permission. Funded in 2012 by Sitra (the Finnish government's innovation fund) after its creators saw that many public “consultations” were negative engagements, Brickstarter aims to help move public involvement from “complain to create”.

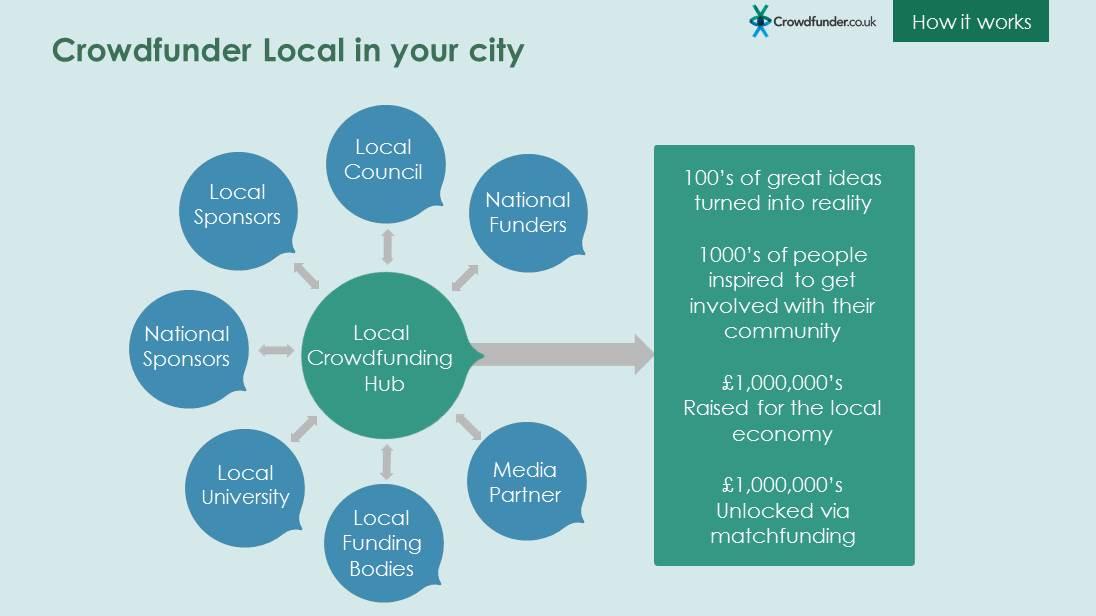

And thirdly some cities are developing their own crowdfunding platform at city level (or at another geographical level). These bring together different funders and city stakeholders to create a dedicated platform tailored to the local context and often 'match' funding raised. A good example is the new #MakeMCR[5] which aims to help people who have great ideas for Manchester to find the help and funding they need to get things done.

"Community crowdfunding platforms are an exciting and empowering tool for local communities. They bring together lots of different stakeholders that want to make things happen in their community and to turn their ideas into reality". Graeme Roy, Marketing Manager, Crowdfunder UK.

There is also potential to take this to another level by combining crowdfunding principles with municipal bonds or community shares for larger public infrastructure schemes or indeed by exploring options to use both of these approaches alongside participative budgeting[6].

What does this mean for your city?

Some will argue that crowdfunding is nothing new. Just think about church congregations who have, for years, raised funds to repair the leaking church roof. The Eiffel Tower is often cited as one of the earliest examples of crowd funding. Others argue that there is no place for crowdfunding in city infrastructure projects and that it encourages public authorities to shirk their responsibilities asking 'where will it end? Will we be crowdfunding pothole repairs soon?'. Where crowdfunding really comes into its own is by letting the community help decide what should happen in their area, and then help to make it happen. By its nature, crowdfunding works on voluntary contributions, which gives funders a personal stake in a given project that they wouldn't have if it were funded by government.

What seems clear is that cities are seeking new approaches to financing and exploring how different combinations can contribute to their priorities, whether they be job creation and enterprise, community development, civic engagement or larger infrastructure schemes. It looks like crowdfunding will be at least part of this urban funding cocktail - in some cases alongside national and EU funding. For examples, cities might use European Structural and Investment Fund Strategies to set up their own crowdfunding platforms or to provide business support programmes which include a crowdfunding element (as in the Westminster example above) or even as matchfunding for community or urban development projects and programmes.

And ESIMeC cities?

After the masterclass, both Sabadell and Basingstoke held local capacity building sessions on crowdfunding. Basingstoke's was with the URBACT Local Support Group (ULSG) whilst Sabadell targeted both local entrepreneurs and ULSG members. Basingstoke is now exploring setting up a dedicated crowdfunding platform to support skills and community projects.

Crowdfunding offers real opportunities for URBACT cities, as they consider resourcing for local action planning and delivery. A city's role may be to develop a dedicated platform or maybe simply to actively broker relationships between local stakeholders and existing platforms. Some cities may believe that crowdfunding is not for them - that it doesn't fit their local situation or legislative context for example - but it seems clear that many will be more proactive about ensuring that crowdfunding is part of our city futures.

It offers a new tool that, at its best, can generate not only funds, but also stakeholder engagement and civic involvement. The message from the ESIMEC network to cities is get informed about alternative finance models, and don’t be afraid to test them out in pursuit of your urban goals.

Photo Credits:

Crowdfunder UK

Extract from ‘Understanding Alternative Finance’, NESTA and Cambridge University, 2014

Impact Hub Westminster

[1] A 'recipe' report that was produced as a result of the transnational event (ins link) also touches upon peer to peer models, timebanks. local exchange trading systems, social clauses in public procurement and microfinance available at http://urbact.eu/esimec-ii

[2] Lead Partner of EVUE and Partner in URBACT Markets

[3] Impact Hub Westminster partnered with the UK Crowdfunding Association, Westminster City Council and Capital Enterprise and was co-funded through a mainstream European Regional Development Fund project - Capital Accelerator.

[4] The Massive Small Compendium are developing a source-book of ideas, tools & tactics for civic leaders, urban professionals, community groups and citizens (http://www.massivesmall.com/)

[5] #MakeMCR is a partnership between We Love Manchester, the Lord Mayor's charity, crowd funding platform Spacehive, a growing number of partners and is supported by the Council which was lead partner of the URBACT II CSI Europe Network