Innovative governance work is notable is several of the 97 URBACT Good Practices. Common themes emerge around how cities are beginning to innovate. Firstly, how they relate and connect to their citizens. Second, how they build new alliances with a wider range of organisations. Thirdly, how for innovative practices to truly function, significant internal change is required from government organisations.

The roots of modern European governance

Governance systems currently in place in much of the European Union were first developed in the 19th Century as the industrial revolution unfolded. Some aspects have changed but often the essential form has remained the same. ‘Management’ as Manfred Weber first documented is bureaucratic and based on rules and procedures, which are systematised through reports, signatures and files. This written paper culture still informs the way of doing business in much of the public sector, even in countries where digital technologies are most advanced. Although flatter hierarchies are now the norm in some countries, elsewhere, rigid hierarchies and promotion based on seniority limit the potential and creativity of younger staff. Everywhere, departmental and professional boundaries restrict our ability to tackle complex problems in a holistic way.

Key characteristics of the old 19th and 20th Century economy were industry and urbanism. Local government responded to these new needs by developing forms of governance that were essentially paternal, aimed at a newly urbanised working class. Their main drive was to deliver healthy enough conditions, enabling a working population to make new industrial products in the workshops of the world.

Changing governance to meet dynamic cities

URBACT challenges such ways of working by proposing integrated and participative approaches. But these are often superimposed on the old structures so that although some relations with the outside world change, the internal organisation remains the same.

In the 21st Century we are slowly beginning to see the emergence of new forms of governance that rebalance the relationship between government and citizens. Instead of redistribution through the raising of tax and the delivery of public services we see the notion of coproduction that puts the service user at its centre. Instead of a one-service model for everyone we see the emergence of personalised models that fit around the individual. But the new coexists with the old and there are inevitable tensions between the paradigms.

Many of the good practices presented at the URBACT city festival illustrate facets of this emerging model of governance. They range from changing internal ways of working, to how the municipality reaches out to citizens through new forms of regulation for common space.

Naples, civic cultural success

Nicola Masella from Naples explained how active civil society movements had taken over vacant and derelict buildings owned by the municipality. Initial success then provoked a reflection inside the city about how this ‘temporary use’ could be organised on a more regular basis, and what form of regulation was needed to facilitate this process. Naples provides and excellent example of how regulatory change can quickly stimulate new activity within the city. Inevitably this activity generates more growth and activity. Here are signs of real change, in other times the response would have been to insist on eviction and increase the security of empty buildings, at cost to the public purse.

By revisiting the notion of civic use, the good practice proposed by Naples city council aims at guaranteeing the collective enjoyment of common goods. These common goods can be cultural and natural heritage, essential public services, public spaces and water resources. Through its willingness and use of its administrative process the city has strengthened civic participation and enabled the fair use of common resources while at the same time allocating clear responsibilities for maintenance and management.

In particular, Naples aims to make spontaneous, bottom-up initiatives recognisable and institutionalised, ensuring the autonomy of both parties involved: the proactive citizens and the institutions.

How it works in Naples: Filangieri Asylum

The first common good to be recognized was the former Asylum at Filangeri, Naples, a complex that in 2012 had been occupied by a group of art and culture professionals protesting against the restoration and recent abandonment of the premises. The city council acknowledged its civic use in a resolution in 2012 which recognised the building as a “place with a complex use in the cultural field, and whose spaces are used to experiment in participative democracy”.

Re-use produces high social and cultural value as well as generating positive economic externalities. Uses must involve not only the users of the space but the whole neighbourhood and the wider city. In return the administration contributes to the operating expenses to ensure an adequate accessibility of the property and general safety conditions: maintenance, cleaning, electricity consumption and surveillance. An ah-hoc unit on the technical level, and a political coordinator are in charge of promoting and fostering an integrated approach particularly, between municipal departments involved and other institutions or agencies.

The facility in its new form has to be free and inclusive, i.e. it must guarantee access to all. Finance comes from donations, voluntary contributions, self-financing and other forms of social pricing, which is permitted for cultural events. The management model must be based on a strong participatory process. In the Asylum Filangieri three different structures manage the building the "Management assembly", the "Steering assembly“ and the “Board of Trustees”. Each has its own distinct remit.

Since the passing of the regulation in 2012 there have been more than 200 weekly open meetings held in the Asylum Filangieri. Working groups are formed as necessary for implementation and over 900 events have been produced with attendance of 18 000 people. The venture has strengthened community cohesion by building bonds between citizens, and has narrowed the gap between artists, academics and citizens.

A second resolution in 2016 recognised a further seven public properties as “relevant civic spaces” and as “common goods”. These facilities have generated 5,800 activities 1,500 days of theatre, dance and music rehearsals; 300 exhibitions; 250 art projects, 300 concerts musical groups plus as many rehearsals and 350 debates. An estimated 200,000 citizens have taken part. In addition, the community-based organisations have provided a range of free services including training for the unemployed, a neighbourhood nursery, schooling for migrants and health services.

The Naples approach puts empty buildings at the service of the community and allows the community’s creativity to flower in a new setting.

Umeå: Governance from a new perspective

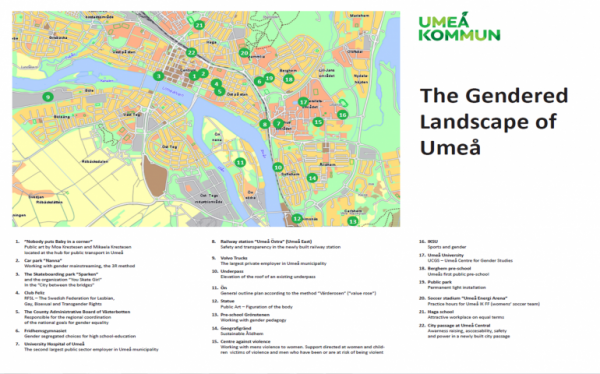

The city of Umeå, in northern Sweden has taken an innovative approach when working towards a more gender-neutral cityscape. Unlike other governance innovation schemes the city has chosen to look broadly at the governance perspective and work towards dismantling a male lead system that precludes the needs and wants of almost half its population.

The city’s municipality began by focusing on how the city works from a gendered perspective. Their practice is to take citizens, policy makers and visitors around the city on a bus tour during which issues facing women and men are explored by visiting different sites in the city and examining them with gender in mind. Interest was ignited when work began on a long pedestrian underpass, used to access the train station, the Lev. This was redesigned with gender equal safety in mind and so is better lit, wide, with no corners behind which people can hide. The main aim of the tour is to view the overall city space and highlight the need for collaboration when creating new, safe, inclusive environments.

Umeå’s approach to improving its urban environment should be celebrated yet its simple, almost obvious idea of inclusive and representative design only highlights the astonishing fact that cities and towns worldwide still do not design educate, design or govern with women in mind. Aside from specialist projects, most major designs that relate to our cities, from the macro level of masterplanning down to the design of public space, schools, hospitals and indeed housing are lead predominantly by men.

Gender balanced governance: Inspirations from Umea

Women mayors are still relatively rare in local government in most of the EU Member States. Even the famous mayors of big cities such as Anne Hidalgo in Paris and Ada Colau in Barcelona are unusual in their own countries. Finding new ways to help policy makers understand issues from a gendered perspective is therefore essential to reach better decisions about design, usage and management of urban facilities. The Umea bus tour which helps people to understand the city from a gender perspective does just this.

Turin opens up to innovation

Fabrizio Barbiero explained how the city of Turin chose to mobilise the innovative capacity of its ten thousand strong workforce in a project called ‘everyone is an innovator’ led by Innova.TO. A challenge was made to the city’s workforce to come up with innovative ideas that were capable of being implemented. Its main aim was to create a cultural shift within the governing body, from being a rule-bound organisation towards a more creative and open structure with a focus on reducing both cost and waste and improving services. 71 project ideas were received in the first round held in 2016. In addition, over 4000 contacts were recorded on the web platform and the initiative has attracted international press coverage as well as in the city itself. One limiting factor at present is that projects must raise their own resources for implementation.

A key aspect of the project is that it is open to regular staff at any level with the exception of directors. Individuals propose most projects but about a third are by two or more staff. The project proposers are anonymous during the selection process which is carried out by a panel which mixes external experts from the University of Torino and the private sector with internal officials. Innova.TO is just one part of wider programmes for social innovation involving communities and other actors in the city.

In the 2016 edition ten projects were taken forward. These included an idea to improve community participation in local projects, a proposal for sensors to control lighting in public buildings, a new model for smart procurement and a method by which citizens can see how their donations encouraged through the income tax submission finance public actions. None of these projects has imposed any cost on the municipality.

The key aim of the project is in changing the perception that only the private sector is innovative. By creating a reflective space for innovation within the municipality the project starts the process by which the public sector can be reinvented. Although it is a bottom up initiative it ultimately depends on senior and middle management for implementation of the chosen proposals. This helps to develop a listening culture among senior managers who need to become more open minded to change.

Aarhus: Culture as an Intermediary

Lars Davidsen from Aarhus presented their approach using culture as a way of intermediating with citizens. Their specific approach has some echoes of what Naples has been doing as they take the opportunity presented by empty properties to create a form of popup revitalisation.

Aarhus is using participation around culture as a way of integrating policy and addressing more complex problems such as loneliness, the inclusion of vulnerable young people and youth unemployment. The use of empty property on a temporary basis allows greater flexibility and for a quick learning by doing approach which might be stifled in a permanent solution.

The city works with a mantra “City life before urban spaces and urban spaces before buildings”

Change in action in Amersfoort and Swindon

The change in workplace culture taking place in some cities has been written about previously in URBACT workstream Social Innovation in Cities with two cities mentioned in particular: Amersfoort and Swindon. Amersfoort’s city manager started a process in January 2015 when he asked his 800 staff to become ‘Free range civil servants’ in the sense that they were asked to go into communities to listen and coproduce rather than staying walled up in the Town Hall. One of the first projects was to develop a former hospital site into an activity park. It showed that co-production could work as a popular planning tool.

In Swindon restructuring of the city’s services created three directorates. All service delivery departments were put in the same department under one director. A second department deals with localities or neighbourhoods while the third is engaged solely in procurement. This radical redesign was aimed at developing services that cost less to deliver and could produce better results for the citizen. But it is only a start, in complex interventions for example concerning troubled families, a host of non municipality agencies are also involved from police and criminal justice to housing associations, job centres and social security. Providing an integrated service to the user can start with the municipality but also needs to address these other fields that are run by other government departments.

Public Administration needs to go Dutch

Our cities continue to change at an increasing rate and yet many of the systems and processes we use to deliver services are groaning under the strain of modern needs. The examples looked at here point to the necessity for a cultural or even philosophical shift in the way we envisage governance engaging with citizens. New, non-hierarchical and inclusive models of governance need to be enacted, systems that represent the needs of every citizen and not simply those within the system. This is perhaps the most challenging aspect. Organisational cultures are very rigid and fixed. Saying that public administration needs to go Dutch is one thing. Doing