In Italy the idea of “city of commons” has been implemented during the last decade. Among the first examples we can describe the “CantiereBarca in Turin”, launched in 2011 to provide people living in a former dormitory area with the means to enhance social inclusion through the rehabilitation of abandoned buildings and several other similar initiatives. Nevertheless, the turning point was represented by the activities implemented by the Commune di Bologna since 2012 when bottom-up initiatives were officially recognized and institutionalized. The process started in 2012 thanks to an initiative launched in the city of Bologna by Fondazione del Monte di Bologna and Ravenna acknowledging the constitutional right of citizens (Article 118(4) of the Italian Constitution) to represent a powerful and reliable ally to public administrations in putting new stimulus, energy, talents, resources, capabilities, skills and ideas to improve the quality of life of the city community. The initiative is based on a “City of Commons” background study presented in Imola during a workshop in December 2011. After the workshop the idea was presented to the city of Bologna whose mayor decided to run an administrative experimentation program. Local residents were facilitated in managing three urban commons (public squares, a piece of network of the “portici” and a public building, all in need of cooperative place making) by city officials and a local partner to test experimental partnerships between the City and its inhabitants. On the basis of the results, and best practices resulting from this test the mayor of Bologna appointed 3 city officials and 2 external experts to draft an innovative piece of local regulation to submit it to public consultation and review by some of the most prominent Italian administrative law scholars. At the end of February 2014 the draft was presented in Bologna and successfully submitted for final approval to the City Council in May 2014. The project was awarded the medal of representation of the President of the Italian Republic and several cities in Italy and proposed and made available to all Italian cities and Mayors.

The city of Verona and subsidiarity pacts with active citizens

The experiences described are both part of a wider network comprising dozens of cities around the world. Nevertheless other cities outside of the Lab.gov.city network are following the pioneering example of the city of Bologna. The city of Verona that adopted its own regulation on the Commons in 2017 after a path started in 2015 when the City Council voted to start a process to manage co-production initiatives. The Verona regulation provides some relevant definition of terms commonly used when referring to the commons topic. More specifically it defines :

• Active citizens: any subject, single individual, association or social group, entrepreneur legally recognized that take initiative for the cure and appreciation of the city common goods;

• Collaboration proposal: a manifestation of interest coming from active citizens aimed to propose appreciation interventions towards city common goods. The collaboration proposal can be spontaneous or answer a call from the City Council;

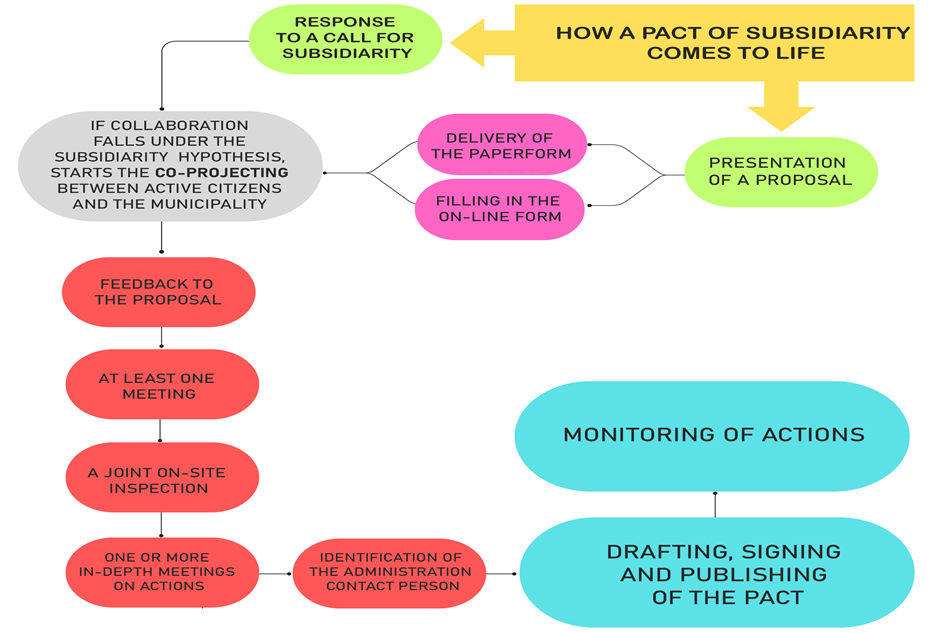

• Subsidiarity Pact: the agreement signed between citizens and the City authorities that describe the topic and main characteristics of the collaboration to enhance the intervention on the city common goods. The proposal presented by active citizens are published on the city website to collect suggestions and recommendations before signing the agreement.

Interventions can focus on both material and immaterial goods and proposals (when admissible), are presented to the public, and the department in charge according to the issues they deal with. The agreement signed make explicit reference to city laws so to give them not only a concrete legal framework but also continuity and stability within public administration. The process leading to the adoption of the regulation of Verona has been based on participation and a bottom-up approach where actions are proposed by the citizens, and evaluated by the city council according to internal guidelines and regulations. The project was structured in five steps : Listening, testing, draft, evaluation, definition of contents and framework. The first phase (listening) was structured as a need assessment analysis, collecting ideas and suggestions from citizens through online semi-structured and multiple choice surveys; the surveys provided ground to propose pilot project to test new collaboration forms and contribute to the definition of the subsidiary regulation. After the collection of all the answers a first regulation draft were published on the City of Verona website to get contribution from citizens. The evaluation phase gave the chance to measure the concrete effects and results of the pilot projects previously enhanced and to test the efficacy of the draft while the last phase is represented by the signature and entrance into force of the Regulation, adopted by the City Council of Verona in 2017. As at 31 December 2022, 60 pacts were active (56.07% of the total), in addition to the 47 collaborations initiated and concluded since 2017 (43.93% of the total). To the approximately 40 municipal officers, involved in the Subsidiarity Pacts, are joined by approximately 4,600 active citizens, plus an estimated number of beneficiaries of the subsidiarity actions, which is around 85,000 citizens. The example of the city of Verona represents shows the effectiveness of involving citizens from the very first steps, and into the definition not only of the projects but also of the framework ruling the co-production initiatives.

Interventions can focus on both material and immaterial goods and proposals (when admissible), are presented to the public, and the department in charge according to the issues they deal with. The agreement signed make explicit reference to city laws so to give them not only a concrete legal framework but also continuity and stability within public administration. The process leading to the adoption of the regulation of Verona has been based on participation and a bottom-up approach where actions are proposed by the citizens, and evaluated by the city council according to internal guidelines and regulations. The project was structured in five steps : Listening, testing, draft, evaluation, definition of contents and framework. The first phase (listening) was structured as a need assessment analysis, collecting ideas and suggestions from citizens through online semi-structured and multiple choice surveys; the surveys provided ground to propose pilot project to test new collaboration forms and contribute to the definition of the subsidiary regulation. After the collection of all the answers a first regulation draft were published on the City of Verona website to get contribution from citizens. The evaluation phase gave the chance to measure the concrete effects and results of the pilot projects previously enhanced and to test the efficacy of the draft while the last phase is represented by the signature and entrance into force of the Regulation, adopted by the City Council of Verona in 2017. As at 31 December 2022, 60 pacts were active (56.07% of the total), in addition to the 47 collaborations initiated and concluded since 2017 (43.93% of the total). To the approximately 40 municipal officers, involved in the Subsidiarity Pacts, are joined by approximately 4,600 active citizens, plus an estimated number of beneficiaries of the subsidiarity actions, which is around 85,000 citizens. The example of the city of Verona represents shows the effectiveness of involving citizens from the very first steps, and into the definition not only of the projects but also of the framework ruling the co-production initiatives.

The commons and civic crowdfunding

Another powerful instrument for enhancing public-private collaborations is represented by the possibility to match public funding with private ones through new technologies. It is the case of civic crowd funding. Even if it is difficult to provide a definition of civic crowd funding due to the definition of civic itself and the wide literature on the topic, we can take as a point of reference the definition provided by Charbit et Desmoulins in 2017 describing the phenomenon as a “significant opportunity for citizens, civil society organizations, and sub national governments to leverage funds for public interest projects, more broadly for projects aiming to improve people’s wellbeing”. Civic crowd funding thus represents an emerging field , and a key tool to achieve a wide range of public interest projects, from social and environmental innovation to urban commons . To date crowd funding for urban commons has produced a number of territory mutations and communities’ projects (distressed areas turned into public parks, local facilities, community centers). Studies on civic crowd funding agree in attributing to it the following characteristics:

• Inspiration from community fundraising models, and resource pooling;

• Small in scale;

• Specific geographical funding area, tackling neighbourhood issues;

• Connection with non-profit organizations (generally).

The local government can participate in four main ways:

• Curate citizens- initiated projects by choosing those to endorse and promote;

• Start local government-run campaigns for specific new projects;

• Use an existing platform for small-scale projects’ procurement;

• Build an in- house crowd funding platform on their own.

The main civic crowd funding platforms are currently located in the U.S.A. and in Europe and represent a concrete chance for citizens to take an active part in financing public activities and projects and to induce municipalities and public authorities to create innovative collaborations and match opportunities.

Conclusions

These three examples are just a representation of dozens of similar initiatives launched and implemented by citizens around the world. They demonstrate how civic society has started to take action and re-gain the power it had delegated to politics and public authorities, and highlight the need to make real change and challenge the current development system to find one that is more human and sustainable. In this sense, a renewed sense of democracy and political opportunity are inspiring citizens and local authorities to develop new governance paradigms that are based on horizontal subsidiarity, collaboration and polycentrism. These principles contribute to a re-orienting of public bodies away from a monopoly position in using and managing common goods towards a shared collaborative governance approach in which all actors are decision makers and co-partners of a shared “commons”. In this sense, “commons” are not only identified as a right, but also as the assertion of the existence of a common stake, without the need to exercise monopolistic public regulatory control over them.

Marco Buemi