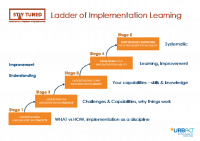

Whilst the Learning Ladder of Implementation gives us a framework to help us understand what we’re dealing with, there are still some other things to consider when developing our understanding of implementation and then applying that new learning within our teams, across our municipality or more widely throughout our wider city partnerships.

In the previous post (Step by Step We Go) we talked about the learning stages for exploring implementation. Here’s a reminder:

Personal Challenges and Personal Learning Journeys

URBACT networks are built upon the principles and methods of transnational exchange and learning between cities. But in practice, the transnational exchange in any one event or meeting is between the individuals who represent cities or other partner organisations.

The learning starts with the individuals in the room. It is those individuals’ abilities (and willingness) to reflect on their own practice, their team’s practice, their city’s practice, which determines success or failure of the learning path. This learning can be a slow process. And it is also a personal process. A unique experience for each individual.

For transnational exchange via Implementation Networks to be successful, individuals, teams, departments and organisations at city level need to change the way they work as a result of the process. But that isn’t straightforward. As the saying goes, “you can’t teach old dogs new tricks”.

Now, I would contest that’s not entirely true – it can be challenging in certain circumstances, but people can and do learn and develop. We see that every day. And the challenges are certainly not governed by age. Resistance to change can and does exist in a whole variety of people and organisations. Learning and applying new ways of working can be challenging for people. Cities and local governance is complex however, and change within such organisations can be difficult, even for motivated individuals.

The Increased Complexity of Organisational Learning

In addition to the personal nature of learning in this context, we must consider that individual learning is (relatively) easy to achieve compared with whole-organisation learning. Even if the whole organisation could be in the room to exchange directly (and let’s ignore the practicalities of that for now..!) it is still harder for large groups than it is for individuals to achieve shared learning and then change their practice deliberately as a result.

To illustrate this, consider that the Learning Ladder of Implementation can be applied separately and simultaneously to the following groups:

- individuals involved the project

- city teams working directly on the TN project

- ULGs involved the project in each city

- wider city administrations and partners working within each local project

In most practical cases, each group will likely be at a different stage and a separate assessment is needed for each of the above groups. The exact composition of each group can be defined at local level and might also change over time. Individuals within a group will normally be at different levels themselves, so making an overall assessment of a group (e.g. of a whole team or of a ULG) can sometimes be difficult and will often require an overall “average” to be taken or an overall judgement to be made.

By working with individuals or groups to assess themselves and build a view of which Stage they are working at, we are trying to help them understand their current perspectives and hence their ability to work with Implementation concepts and to actively learn about implementation capabilities and practice. We are not assessing them to provide a score or any “true” picture of their situation.

We are assessing in order to help focus learning and drive improvement. Being “assessed” by an outsider in this context will rarely yield good results for an individual or team. Self-assessment in this context is therefore crucial to build buy-in. Support and challenge may be required, but the individual or team in question has to own and believe in the results.

For improving implementation capability and practice, the aim is to move as many of the above groups to as high a Stage as possible. This is easiest with Group A (individuals) and hardest with Group D (whole organisations or ecosystems).

The Tension of Looking at Implementation in Isolation

Whilst we need to acknowledge implementation as something in its own right in order to study it and improve how we do things, the fact remains that “Implementation” doesn’t exist on its own. We have to be implementing something for it to have any tangible meaning. We can’t try things out without having a set of plans to realise or a project to deliver, for example. So it follows that when applying our learning about implementation, we still have to apply it to something.

This creates a tension or conflict: on one hand, we need to treat implementation as a concept in its own right in order to study and explore it; but on the other hand, we can’t do anything practical with it unless it’s linked to a specific, real situation.

To study implementation and understand how we can apply learning from one context into another context, we need to isolate the practice of implementation and look at the principles, themes and common threads. This means separating those and abstracting the core principles, to be considered separately from any specific policy or specific cases. But when it comes to applying all that to our practice back home, we need to consider the specific cases in which we might apply those principles and approaches and tailor that to fit the local context.

Putting it all back together again

The links between the transnational and the local level are also crucial. Compared with other types of exchange on policy (such as the URBACT Action Planning Networks) the transfer of learning points from transnational to local level within Implementation Networks is potentially even more challenging, precisely for all the reasons outlined above.

Those returning from the transnational meetings need to be able to convey some complex concepts effectively, when sometimes having only just been introduced to those ideas themselves. This is harder to do with gravitas if you are a relative novice in the subject. On top of that, an understanding of the structure and/or framework is needed to help communicate it in any deliberate or coherent way. Again, such frameworks might be newly-introduced and therefore more difficult to explain and use convincingly in the cold light of day, away from the original workshops and discussions.

So the focus and design of the transnational meetings becomes about creating the conditions whereby the participants feel comfortable in challenging themselves and each other about how they work. And by how “they” work, this often means how “they personally” work. There are both country-level cultures and organisational-level cultures at play in that process, in addition to personal behaviours and working styles. Some are more open to challenge and reflective practice than others.

But the core point is that individuals need to be able to recognise and acknowledge their own development areas and those of their team. Then later on when back at home they need to have the tools to be able to work with people who were not in the room during the transnational exchanges – to help those people with their own (personal) reflections and learning journey.

The transnational exchange therefore tended to be based around one or more of these “abstract” implementation themes. But in Stay Tuned we attempted to link these back to concrete examples and give participants space to discuss and explore what it meant to them. This certainly kick-started the thinking and change of perceptions. But in reality, many network participants commented that the real thinking about how to apply the learning happened with colleagues on the plane home! And that is no problem at all.

So much of the application of any new learning is carried out on a local level, when participants had the opportunity to change something in practice, back in their own city. Many of the fruits of the transnational exchange are not seen at the transnational or network level but at local level, as we change our processes, our interventions or (in the case of implementation learning) by changing how we work on projects and how we deliver changes in our cities.

Modern cities face many complex problems and reducing Early Leaving from Education and Training (as in the case of Stay Tuned) is no exception. We must use implementation approaches that are suited to these complex contexts. And this often requires changes to how we work, as individuals, as teams and as partnerships.

We can learn new tricks, but we need to be motivated to change ourselves, change our expectations, change how we think about challenges and how we work with others to solve them. The right framework, the right focus and the right support can make that possible. This is what we have seen in Stay Tuned.

Ian Graham

Lead Expert, Stay Tuned