This article addresses two questions:

How can we work together in communities to make better public spaces?

How can play be used to create the momentum and focus for placemaking?

The article follows on from an online transnational meeting held on 11 February 2022 where play and placemaking were explored by partners in the Playful Paradigm Second Wave Project.

By Wessel Badenhorst

URBACT Ad Hoc Expert

April 2022

Play and Placemaking – a perfect match for great public spaces

by Wessel Badenhorst

When we think about placemaking in public spaces we might be tempted to judge a place just on its physical appearance. If that was the main factor to improve a place, then it will be sufficient to get a landscape architect to design a plan and the municipality to spend the money on its implementation.

Yet we know that many ‘well designed spaces’ end up being less appreciated in the neighbourhoods and communities where they are located. Why? There is a simple answer to this question. The secret to what makes a great place is not only in its appearance or ‘functionality’, but is rather determined by four main factors. These are:

the range of actual uses and activities of people in the space throughout the day and week;

the sociability of the space, especially as a location for meeting people and socialising;

the ease with which the space can be accessed irrespective of the users’ abilities together with the variety of transport modes available to connect to the space;

the image of the space (i.e. physical appearance) in addition to the perceived comfort and safety associated with the space.

The Project for Public Spaces, a New York-based organisation that have been at the forefront of promoting the value of public spaces in the everyday lives of people living in cities, developed the Place Diagram (see below) to help placemakers use metrics to evaluate a public space and to plan and implement actions to improve the space.

A working definition of placemaking follows from this systematic approach to public spaces namely:

Turning public spaces into great places by increasing the presence of people through user participation and stakeholder cooperation.

From this definition it is clear that how people interact with a place is at the core of the understanding of how we should develop public spaces. It is also acknowledged that stakeholders will have different perspectives to what is valued in a specific public space. For example parents or grandparents accompanying their young children or grandchildren will have a different perspective on the use of the space than for example teenagers or young people. The art of placemaking thus requires a process of facilitating discussions and ideas from as many stakeholders as is practically possible to identify matches between needs and actions that will improve the space.

The process of placemaking can be understood as consisting of five stages and follows the logic of analysis and planning preceding implementation and evaluation. A good start will be to define and map the space in question and to identify who are key stakeholders that should be involved in the process.

The quality of outcome (i.e. a better, even great place) is often closely related to the depth and breadth of participation from stakeholders in the process. This starts with the evaluation of the space and the identification of issues, which requires the use of observation tools and creative participation activities.

The conversations between stakeholders together with the data from the space observations will inform new insights into what the space can be for as many types of users as possible. A critical part of placemaking is to visualise these insights and design professionals make valuable contributions to this end.

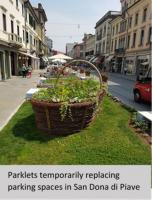

Placemaking however is an iterative process. Ideas generated in the discussions, need to be put into practice and tested. Many ideas are not new (i.e. have worked in other places), but stakeholders need to feel how it works when ‘in place’. Also, change is never easy and by doing a temporary installation (see picture of the parklet), a change can be rolled back or tweaked.

These short-term experiments often lead to more informed decision making in an ongoing re-evaluation of the space that creates more certainty for longer term investments and improvements.

By getting involved in a placemaking process, stakeholders tend to get to know each other and hopefully develop mutual trust. This is so important for the ongoing management of a space and especially to continue starting initiatives to animate and activate the space while also promoting active stewardship (i.e. looking after the place) among the users of the space.

In URBACT’s Playful Paradigm Project, a further dimension to placemaking has been explored. How can play be used to activate public spaces and meet the needs of users of these spaces? If playfulness is inculcated through several play activities in public spaces in a city or in specific neighbourhoods, will it result in building social inclusion and affecting the general wellbeing of communities?

In the Playful Paradigm Project the following conclusions were reached on the association of play making and placemaking:

Play brings people together. Placemaking brings people together. It is a perfect match!

The emphasis in placemaking is often on activities to animate public spaces and play is an excellent way to do this.

Placemaking is about going ‘cheap and cheerful’, especially re-using and repurposing materials (i.e. circular economy). Creating playful places is also about using affordable materials like chalk or even natural objects like the trunk of a fallen tree.

It helps to have a targeted approach in play making and placemaking for example the needs of target groups such as young people, older people, women and girls. This will influence aspects such as types and times of play, safety and who to include in the placemaking process.

The Project also practically demonstrated in partner cities that through play strong community participation can be activated. The initial play activities and experiments can lead to further cooperation and collaboration in the interest of community development.

In conclusion, if any group of people want to start a project to improve a public space in their neighbourhood or in the city centre, it makes sense to follow the stages of placemaking described in this article and to build a strong element of play into the process! Let’s play and make!