Designing tourism for the future of work increasingly means designing for people who arrive with a laptop, stay longer than a weekend and blend work with everyday life. For coastal and heritage cities in the Remote-IT network, and for many other European destinations, digital nomads and remote workers are no longer a niche. They are part of a broader rethinking of tourism, seasonality and local development.

This entry explores how remote work can support more balanced, year-round and sustainable tourism, what this means for policy and planning, and how cities can use the Remote-IT experience as a starting point for their own strategies.

Why seasonality still defines tourism in much of Europe

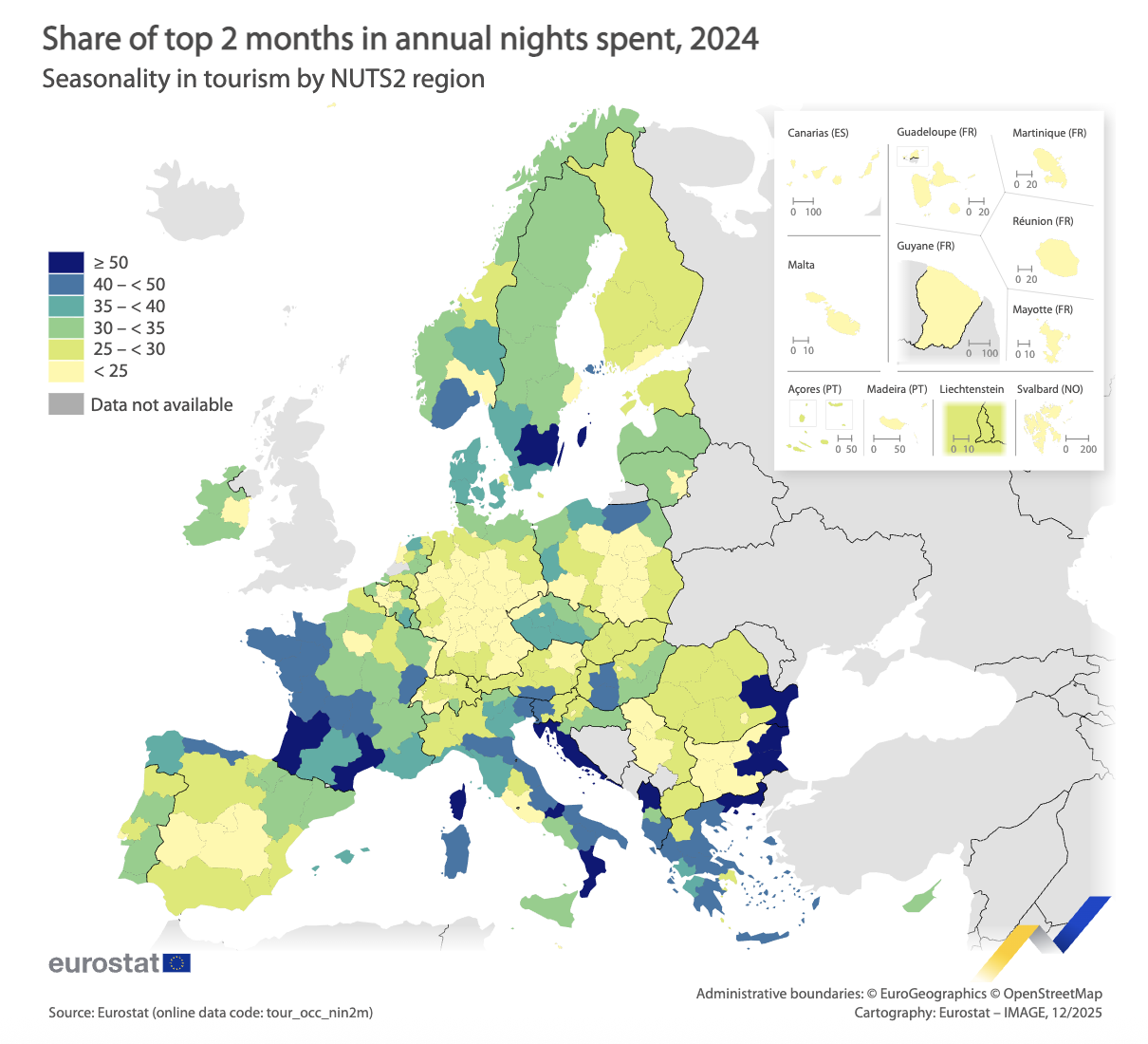

Tourism in Europe remains highly seasonal, especially in coastal and heritage destinations that see a sharp summer peak and long low seasons. Eurostat data for 2024 shows that nearly one-third of all tourism nights in the EU were spent in just two months, July and August. The strongest seasonality was recorded in Croatia, Greece, Bulgaria, Albania and Montenegro, precisely the types of places where Remote-IT partner cities are located or where their visitors come from.[1]

At the regional level, 1 in 6 EU NUTS 2 regions concentrate more than 40 percent of their annual tourism nights in the top two months. Coastal regions are among the most seasonal, while capital regions tend to be more balanced.

Source: Eurostat

There are the structural consequences of this pattern- overcrowding and environmental stress during the peak season, underused infrastructure and unused capacity the rest of the year, temporary jobs, and pressure on community life as cities are forced into a “feast or famine” model of visitor flows.

For cities like Dubrovnik, Heraklion or Câmara de Lobos in the Remote-IT network, this is a familiar reality. Summer brings congestion, high housing pressure and overtourism debates, while winter can feel empty, with closed businesses and limited cultural activity. Remote-IT cities explored a shared question: can remote work help smooth the extremes of tourism seasonality in a way that is sustainable for residents?

Digital nomads, “workationers” and long-stay visitors: who are we talking about?

From a tourism perspective, not all remote workers are the same. The Remote-IT playbook distinguishes remote workers primarily as labour market actors, but for this entry the focus shifts to their role as visitors and residents-in-transition.

Drawing on recent studies, we can identify three overlapping segments that matter for tourism and local development:

- Digital nomads- people who move between countries while working fully remotely. Recent estimates put the global number of digital nomads in the tens of millions. Global platforms such as Nomad List and Flatio show that Portugal, Spain and other European countries consistently rank among the most popular destinations.

- Workationers- employees or freelancers who temporarily relocate for 2–8 weeks to combine work and holiday in a single destination. Research on workations in European cities finds that this segment tends to stay longer than typical tourists, value good internet and co-working options, and often travel outside the peak season.

- Slowmads, returnees and diaspora remote workers- people who stay several months or return regularly to their region of origin while continuing to work for employers elsewhere. This category is especially relevant for Central and Eastern European cities with large diasporas and can blur the line between tourism, circular migration and long-term settlement.

For cities, this matters because these visitors behave more like short-term residents than tourists: they shop in local supermarkets, use public transport, search for long-stay rentals, and participate in everyday community life. They are also less tied to traditional holiday calendars. While classic tourism peaks in July and August, many remote workers prefer quieter “shoulder” months that offer lower prices and more livable conditions.

Linking remote work, sustainable tourism and climate resilience

The acceleration of remote work corresponds with growing concern about overtourism and climate impacts. Heatwaves, extreme weather and overcrowded destinations are already pushing travellers towards “coolcations” and shoulder-season trips. Travel industry data for 2025 shows rising demand for northern and cooler destinations, as well as for travel in spring and autumn, as tourists try to avoid extreme summer temperatures and over-crowded hotspots.

This shift aligns naturally with remote work:

- remote workers can avoid peak-heat months and choose more temperate seasons

- they can stay longer, reducing the relative emissions per day of stay compared with frequent short trips

- they are often more aware of their environmental footprint; survey data suggests that more than 40 percent of digital nomads list climate action or environmental impact as a concern in their travel choices.

Remote-IT cities, particularly those with strong tourism brands, have been integrating these considerations into their Integrated Action Plans: looking at how coworking spaces, local entrepreneurship support, green mobility and cultural programming can be coordinated to create livable year-round environments that work for residents, remote workers and visitors alike.

Photo: Remote-IT team in Camara de Lobos, during the transnational meeting

Emerging lessons from European practice

Although systematic evaluation of remote-work tourism programmes is still limited, several strands of evidence from Europe and comparable contexts are already useful for cities.

Remote work as part of regional development strategies

OECD’s 2023 report Attracting talent: The (no longer) remote option for regions and cities[2] notes that regions and cities are increasingly using remote work to offset demographic decline and stimulate local economies. Strategies include financial incentives, branding initiatives and support for soft-landing services.

Complementary research on remote work in rural areas in the Nordic and Baltic regions finds that remote work can help spread in-migration across municipalities, support local services and strengthen community life, provided that basic infrastructure and local capacity are in place.

These findings are mirrored in the Remote-IT network, where smaller and medium-sized cities- from coastal municipalities to university towns, see remote work not just as a tourism strategy but as part of a broader agenda to retain and attract residents, support SMEs and make better use of existing housing and service infrastructure.

Workation programmes and curated stays

Workation destinations do not simply market themselves as “nice places to visit”. They develop concrete packages that make it easy for professionals to live and work there: reliable internet, coworking spaces, curated accommodation, local hosts or community managers, and clear information on visas and registration.

Practitioners who have worked with rural towns in Switzerland, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Czech Republic emphasise that what matters is not the volume of remote workers but the consistency. In many cases, 20–40 long-stay professionals in low season are enough to keep local businesses open and give “life” to a town. They stress that municipalities must invest in the first editions of such programmes- through modest budgets, tourism board involvement and local coordination- if they want long-term impact.

For Remote-IT cities, this translates into a pragmatic lesson: remote work tourism is not a mass-market product. It is a targeted, curated proposition that combines urban development, tourism and innovation policy.

A practical agenda for cities: from experiment to integrated strategy

Because other entries in the Remote-IT playbook already cover destination branding, talent attraction and the internal transformation of public administrations, this section focuses specifically on the tourism-seasonality interface. Here is a set of questions and steps cities can use as a checklist when considering remote work as a tool for sustainable tourism:

1-Start from your seasonality map

Cities and regions should begin by mapping their current tourism and population patterns:

- When are streets, public spaces, transport and services under most pressure?

- Which months see under-use of accommodation, venues and cultural institutions?

- How do these patterns differ between neighbourhoods, and between residential and tourist areas?

2- Clarify what you want remote work to achieve

Remote work is a means, not an end. Cities should define explicitly whether they are trying to:

- extend the tourism season

- diversify the local economy and support SMEs

- attract potential long-term residents

- revitalise specific neighbourhoods

- support rural or peripheral areas in the region.

3- Design “remote-ready” offers for the right months

Rather than generic campaigns, cities can develop specific offers targeted at low and shoulder seasons:

- co-working and co-living packages valid between, for example, October and April

- thematic programmes tied to local culture (winter festivals, gastronomy, hiking, cultural residencies)

- collaboration with local universities and innovation hubs to host remote professionals for project-based stays.

4- Integrate tourism, housing and community perspectives

To avoid negative side effects, remote-work tourism strategies need to be co-designed with:

- housing departments and local housing providers

- social services and community organisations

- resident groups and neighbourhood councils.

5- Monitor impacts and learn iteratively

Because remote-work tourism is still an emerging field, cities should treat early programmes as experiments rather than fully fledged permanent policies. This implies:

- collecting data on length of stay, seasonality, spending patterns and satisfaction of both remote workers and residents

- tracking indicators such as rental prices, business openings/closures and usage of public spaces

- sharing results through networks like URBACT so that other cities can learn from successes and failures.

Positioning remote work within a broader sustainability agenda

Digital nomads and remote workers are not a silver bullet for the structural problems of tourism. But they do offer a specific way to move beyond the traditional “high season vs low season” mindset and towards a year-round, resident-centred approach to place development.

For Remote-IT cities, the core insight is that remote work strategies must be anchored in an integrated vision:

- Economically, remote workers can bring more stable revenue, support local businesses outside the high season and generate demand for higher-value services rather than volume-driven tourism.

- Socially, they can enrich community life and create opportunities for knowledge exchange, provided that housing and inclusion are managed carefully and residents are not priced out.

- Environmentally, longer stays and off-season travel can reduce pressure on fragile ecosystems and infrastructure.

- Institutionally, working on remote-work tourism forces cities to break silos between tourism, digitalisation, housing and economic development, something that is at the heart of URBACT’s integrated approach.

The Remote-IT network invites cities to see digital nomads, workationers and other remote workers not just as visitors, but as potential partners in building more resilient, liveable and future-ready places.