Cities that experience URBACT for the first time rarely want it to end.

Not because of funding, documents or logos, but because URBACT is about people, cooperation and very concrete tools for working with and for local communities.

This was exactly the case for the PUMA network.

Over 2.5 years partners worked together within the URBACT IV Action Planning Network. They represented very different realities: large and medium-sized cities, small municipalities, rural regions, regional agencies and a university. Their institutional roles, planning traditions and levels of experience in sustainable mobility varied widely.

What united them was not a shared solution, but a shared challenge: how to move from mobility projects to mobility practice.

Then: familiar challenges, uneven starting points

When PUMA started, the baseline picture was clear. Across the network, partners faced a set of recurring and well-known challenges:

strong dependence on private cars,

fragmented or insufficient data,

limited coordination between transport, spatial planning, climate, health and social policies,

very different levels of experience with Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs),

and soft measures - communication, participation, behaviour change - still too often treated as secondary to infrastructure.

The Baseline Study showed cities at very different stages of their mobility journey. Some were already working with advanced strategies and monitoring systems; others were just beginning to frame mobility as a strategic policy field. What many shared, however, was a sense that plans too often remained documents, rather than tools for implementation.

Learning together: where the real value of the network emerged

What changed during PUMA was not the challenges themselves, but the way partners approached them.

Through transnational meetings, peer exchanges, study visits, thematic discussions and continuous support, the network gradually built a shared understanding of integrated mobility planning. Learning flowed in all directions.

Partners benefited from different types of expertise. Academic input, including contributions from the University of Zagreb, supported methodological discussions around SUMP quality, data, indicators and long-term planning logic. At the same time, cities learned most strongly from each other’s practice.

Viladecans and Gdańsk inspired others with their experience in cycling promotion, communication campaigns and soft measures, showing how everyday narratives and engagement can support modal shift.

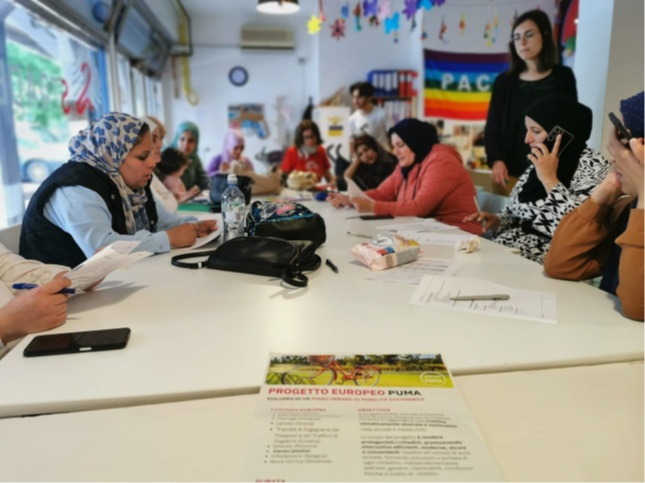

Cento brought a very grounded inclusion lens into the discussion - linking mobility directly to access to services, jobs and everyday life for residents living in its hamlets. The Baseline Study highlights that limited public transport can lead to socio-economic marginalisation of specific groups, including migrants and women without a driving licence, alongside older residents and young people.

This is why flexible solutions such as on-demand transport were explored as a relevant response to low-density contexts and underserved groups, where conventional public transport struggles to meet everyday needs.

This perspective helped shift the discussion across the network - from mobility as infrastructure to mobility as access, and from “average users” to people whose daily choices are shaped by gender, income, legal status or care responsibilities.

This learning was hands-on: partners from Tauragė and Dienvidkurzeme travelled to Italy to explore these approaches on site and discuss openly what could, and could not, be transferred to their own territories.

Throughout the process, the network was held together by continuous facilitation: translating European frameworks into local realities, connecting very different partners, and keeping a strong focus on integration, implementation and learning across contexts. This combination helped cities not only improve their plans, but also gain confidence in how they address mobility challenges.

What changed on the ground: a snapshot of the Integrated Action Plans

The diversity of Integrated Action Plans (IAPs) developed within PUMA reflects both the variety of local contexts and a clear shift in planning logic.

Some IAPs focus on neighbourhood-level interventions: safer walking environments, cycling connections, school streets and people-first public spaces. Others address mobility at city or regional scale, tackling public transport accessibility, flexible solutions for low-density areas, or stronger links between urban centres and their surroundings.

One concrete example of this shift can be seen in Cento. At the start of the PUMA journey, mobility discussions in the city focused primarily on infrastructure gaps and limited public transport coverage. Through exchanges within the network, including on-site discussions with partners facing similar challenges, the focus of the Integrated Action Plan evolved.

Instead of framing mobility mainly as a transport supply issue, Cento’s IAP increasingly addressed access to everyday services for residents of its hamlets, particularly groups with limited mobility options such as migrants, women without a driving licence, older residents and young people. This shift helped reposition flexible solutions, including on-demand transport, from a technical experiment to a strategic inclusion tool embedded in the IAP.

The network also explored less typical planning scales. In Croatia, the University of Zagreb developed an IAP focused on the national level, proposing a structured support framework to help cities prepare and implement high-quality SUMPs. In cross-border contexts, such as Nova Gorica and Gorizia, mobility planning became a tool for cooperation, integration and shared urban identity.

Despite these differences, all IAPs share a common approach. They combine infrastructure with governance, funding, data and stakeholder engagement and are designed as implementation-oriented tools, rather than stand-alone strategies.

From experience to guidance: what PUMA offers beyond the network

The lessons emerging from this collective work are captured in the final PUMA product, developed as a practical resource for other European cities and regions.

The conclusions emerging from PUMA point clearly to one overarching message: small and medium-sized cities cannot deliver meaningful mobility transitions without stable, long-term support.

Across the network, cities faced growing expectations - climate targets, road safety standards, accessibility requirements and new EU regulations - while operating with limited staff capacity and short-term project-based funding. This gap between ambition and resources was a recurring theme throughout the PUMA journey.

First, cities need predictable funding. Developing and implementing Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans requires investment not only in infrastructure, but also in analysis, participation, communication, monitoring and behaviour-change measures. Without long-term financial stability, cities are forced into short project cycles that do not match the long-term nature of mobility transitions.

Second, cities need access to flexible financing tools. Many small and medium-sized municipalities struggle to prepare investment pipelines, bundle projects or secure co-financing. National SUMP support programmes, now required across the EU, should help cities access grants, loans and technical assistance, and support the packaging of smaller interventions into fundable portfolios.

Third, technical assistance must become a standard, not an exception. Cities need ongoing support in data analysis, feasibility studies, stakeholder processes, scenario modelling and monitoring frameworks. Many mobility departments are small, overstretched or relatively new; without expert support, plans risk remaining formal documents rather than implementation tools.

Fourth, capacity building is essential. Integrated mobility planning requires new skills - from cross-sector thinking and communication to behavioural insights, gender and safety considerations, and climate literacy. PUMA demonstrated how powerful continuous learning and peer exchange can be when properly supported. This type of learning should not end when projects end.

The experience of PUMA also underlined the importance of long-term cooperation between cities and knowledge institutions. Academic partners can play a stabilising role - supporting methodological quality, data use, monitoring frameworks and strategic consistency over time.

The national-level IAP developed by the University of Zagreb illustrates how this cooperation can move beyond advisory input and become a structural element of mobility governance, helping cities translate European requirements into workable national and local frameworks.

Finally, responsibilities must be clearly shared across governance levels. While local authorities lead the planning process, national and regional actors must create the conditions that allow cities to succeed by coordinating standards, ensuring stable resources and providing long-term institutional support.

These needs are not theoretical. They are grounded in the everyday experience of PUMA cities and they define what it will take to make integrated mobility planning a genuine standard across Europe.

Rather than promoting a single model, it distils insights that proved relevant across very different contexts:

Integration needs structure.

Coordinated governance, clear roles, shared data and political backing are essential if integrated mobility planning is to move beyond slogans.Soft measures are core measures.

Communication, education, testing actions and participation are not add-ons, but key drivers of behavioural change.Context matters more than scale.

Smaller cities and rural areas often benefit most from flexible, low-threshold solutions such as on-demand transport, safe walking and cycling conditions, and improved regional connectivity.Capacity is as important as infrastructure.

Knowledge partners, competence centres and universities can help stabilise planning quality and build long-term confidence within local administrations.Plans must be implementable.

Linking actions to funding sources, monitoring frameworks and existing strategies is what turns ambition into progress.

These conclusions are grounded in real plans, real constraints and real cooperation - not theory.

Beyond documents: a change in perspective

One of the most lasting outcomes of PUMA lies beyond strategies and action plans.

For many participants, the network marked a clear shift in how they understand mobility itself. What initially appeared as a technical or sectoral issue gradually became a lens through which broader questions of accessibility, inclusion, health, climate and quality of life were addressed.

Working closely with peers from other countries helped local teams challenge their own assumptions and see familiar problems from new angles. For some, this meant moving away from car-centred thinking; for others, recognising the importance of soft measures, participation and everyday user experience.

This personal and professional growth, visible across local coordinators, municipal teams and stakeholders is what makes the results of PUMA more resilient. Plans can be revised, but a changed way of thinking tends to stay.

Not the end, but a shift

PUMA did not aim to solve all mobility challenges in 2.5 years. What it did achieve was something more durable.

It helped cities move from isolated projects to integrated strategies, from documents to implementation, and from learning alone to learning together.

For many involved, PUMA was not the end of a journey but the moment they realised they wanted more of URBACT. And perhaps that is the clearest sign of success.