Across Europe, cities are investing heavily in cycle lanes, cleaner buses, and new mobility services. Yet many still struggle with a familiar problem. The infrastructure is there, the policy ambition is clear, but people continue to travel much as they always have. Cars remain dominant, even where alternatives exist.

At a gathering of European cities in Hradec Kralove, Czechia, this tension sat at the heart of the conversation. The meeting, part of the Beyond the Urban network, brought together local authorities working on mobility challenges that stretch far beyond dense city centres. Rural areas, small towns, and peri urban regions face particular difficulties, where distances are longer and habits deeply ingrained. What united the participants was a growing recognition that sustainable mobility is not only a question of transport systems, but of human behaviour.

The workshop, titled Making Sustainable Mobility Stick, set out to challenge a persistent assumption in transport planning, that if people are given information about environmental benefits, or if new services are provided, behaviour will naturally follow. Experience suggests otherwise.

From personas to people

Many of the cities present had previously worked with tools such as personas to understand different types of travellers. Parents juggling school runs, older residents in rural villages, shift workers with irregular hours. Revisiting this approach proved revealing. It reminded participants that mobility decisions are rarely rational calculations. They are shaped by routines, social expectations, perceived convenience, and subtle cues in the environment.

This person-centred perspective laid the groundwork for introducing behavioural science. Rather than asking why people do not make sustainable choices, the workshop asked a different question. How are current systems and environments nudging people towards unsustainable ones?

The hidden architecture of choice

The hidden architecture of choice

Behavioural science focuses on what is often called choice architecture. The context in which decisions are made. This includes what options are most visible, which are presented as normal, and which require extra effort.

During the workshop, participants were introduced to a practical set of behavioural principles that increasingly influence public policy. These included nudging, social norms, default options, framing, incentives, and feedback loops. None of these remove choice. Instead, they shape how choices are perceived.

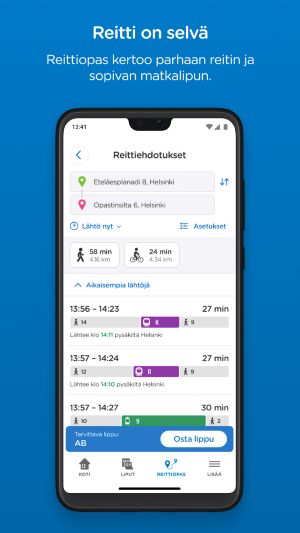

A simple example is default options. When a navigation app automatically suggests a driving route, it reinforces car use as the norm. When walking or cycling routes appear first for short journeys, behaviour often shifts without any regulation or persuasion. Similarly, social norm messages that show how many people already use public transport can be more effective than messages about carbon emissions alone.

Spotting the difference between information and influence

One of the most telling moments of the workshop came during a group exercise. Participants were presented with five mobility interventions and asked to identify which one was not behavioural. Four relied on principles such as commitment, gamification, social norms, or defaults. One was a traditional information leaflet about environmental benefits.

The discussion that followed reflected a wider shift taking place in many cities. Information still matters, but on its own it rarely changes behaviour. Interventions that work with habits, emotions, and social dynamics tend to have a far greater impact.

Learning from cities that changed the rules

The workshop also drew on examples from across Europe that illustrate behavioural thinking in practice. Some were subtle, others more structural.

In Zurich, strict limits on parking supply have quietly reshaped how people move around the city over decades. In Pontevedra, a simple walking map known as the Metrominuto reframed distances, making journeys on foot feel shorter and more manageable. In Antwerp, parents changed school travel routes when given clear guidance on cleaner, less polluted paths. In rural parts of the UK, Wales, and Germany, demand responsive transport services have reduced car dependency by fitting around people’s lives rather than fixed timetables. What these examples share is not a single solution, but a common insight. Behaviour changes when sustainable options are easier, more visible, and socially reinforced.

Why this matters now

Behavioural science is no longer confined to academic journals or national nudging units. It is becoming part of everyday urban policy, from transport and energy to health and waste. For cities grappling with climate targets and limited budgets, the appeal is clear. Behavioural interventions are often low cost, adaptable, and capable of delivering measurable change.

The discussions in Hradec Kralove suggested that many local authorities are ready to go further. Not by telling people what they should do, but by redesigning systems so that sustainable choices fit more naturally into daily life. Making sustainability mobility stick, it turns out, is less about persuading people to change who they are, and more about changing the environments in which decisions are made. For cities across Europe, that shift in thinking may be just as important as any new piece of infrastructure.