Measuring the social impact of urban regeneration: accompanying European cities on their impact journeys

What is the social impact of urban regeneration? The URBACT network of ten European cities, U.R. Impact, aims to answer precisely that question. By prioritising social impact with a focus on community involvement, urban regeneration actions are rethought by placing citizens and their social, economic, and environmental well-being at the centre of the processes. It also allows for an increased sense of belonging and civic participation. Ballymahon in Longford (Ireland), Bielsko-Biała (Poland), Bovec (Slovenia), Brumov (Czech Republic), Cinisello Balsamo (Italy), Hannut (Belgium), Kamza (Albania), Mértola (Portugal), Murcia (Spain) and Targu-Frumos (Romania) embarked on the journey of social impact measurement in the context of their specific urban regeneration projects. With very different starting points and contexts, they are each experiencing their own challenges and learning from one another. This article is a short account of their progress so far, and an attempt to draw preliminary learnings from this leading edge urban social impact measurement project, one of the first on such scale in Europe.

Impact measurement is a complex endeavour to start with. Social impact is probably the most difficult to measure compared to environmental or economic ones. The urban context adds even more complexity, covering intertwined systems, far outweighing any challenges typically found by single public institutions, businesses or non-profits. This makes urban social impact measurement an incredibly exciting methodological challenge that is still in its nascent stage in most cities globally. The U.R. Impact cities are thus some of the trailblazers, allowing for rich learnings to be gained underway for other urban areas. How did they approach this challenge?

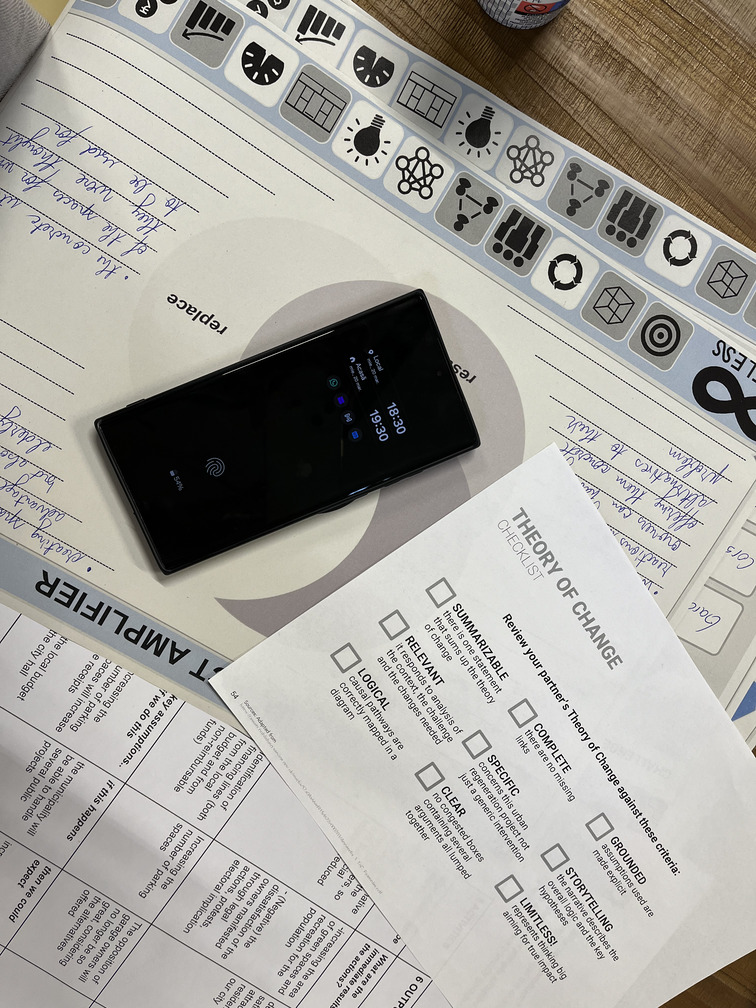

Guided by the ad hoc expert Lidia Gryszkiewicz of The Impact Lab, and with the strategic support of the lead expert Liat Rogel, the ten U.R. Impact cities have been refining the theories of change for their urban regeneration projects. A theory of change, often referred to as the impact chain or the logic model, starts by looking at the desired target impacts and then designing the specific inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes that would lead to these impacts.

While it might sound simple, it is crucial that the desired impacts actually answer the needs of various involved stakeholders. Indeed, multi-stakeholder engagement is an indispensable part of any serious impact planning, especially in the social domain. For this reason, U.R. Impact cities have been working together with their Urban Local Groups (ULGs), using tools such as "Stakeholder Impact Vision" to truly understand the needs and ambitions of their different stakeholder groups. The latter typically involve categories such as citizens, local authorities, NGOs, businesses, and other urban service providers. The specific groups depend on the concrete urban regeneration challenges being tackled. And so, for Cinisello Balsamo, facing a complex process of temporary school relocation due to a renovation project, it is key to take into account the perspectives of school authorities, parents, students, local inhabitants, and business owners. For Longford, working on the regeneration of buildings to host core urban services (senior care, childcare, youth activation, and many more), or for Bovec, investing in a multi-generational activation project, the citizens, service providers, and local authorities are the core groups to include. Targu Frumos, working on a specific challenge of recuperating green spaces from private garage owners, the latter's views are key to take into consideration. For places where the scope of urban regeneration covers the city centre, such as Bielsko-Biała, Broumov, Hannut, and Kamza, or even the whole city, such as Murcia or Mértola, involving all core urban stakeholders is necessary. Indeed, an URBACT process is a great opportunity to involve different stakeholders in the ULG. But stakeholder engagement should often go further than that. To establish a joint social impact vision, oftentimes it is necessary to get in touch with the key groups directly. Depending on the scale of urban regeneration, cities have seen great success in formats such as social media polls, post surveys, or door-to-door conversations. While digital solutions allowing for citizen engagement with a tap on a smartphone keep gaining popularity, personal conversations, from short face-to-face interviews to elaborate social innovation labs, remain the most effective ways of gaining rich insights on stakeholders' needs and dreams for their cities.

And so, in Mértola, for instance, a Portuguese town with a very small population, these personal connections with citizens are proving to be the core source of information. While Mértola is building an advanced system of impact indicator monitoring based on broad datasets, it is exactly the in-depth conversations that the citizens, visitors, and authorities are holding during the local events that are allowing the city leaders to stay on top of the local developments and plan for ambitious urban regeneration initiatives in the city. For example, Mértola has been successfully turning the local challenge of extreme local weather conditions (heat further exacerbated by climate change) into opportunities, such as setting up a prestigious research centre on natural sciences, or engaging in renovation projects aiming to increase the shadow area of public spaces.

Bielsko-Biała, a dynamically developing city in the south of Poland, while leveraging the legally obligatory citizen consultation process, is considering more in-depth participation methods to complement the basic participatory requirements with richer and broader inputs.

The strategy and urban revitalisation department is at the forefront of these changes, looking at new and more effective ways of making the co-creation of urban regeneration a reality. Ideas abound in the historic city centre, where some important revitalisation works have already seen success, and major new developments like the future opening of a prestigious university campus, are opening doors for more active multi-stakeholder engagement opportunities.

Other cities are at the start of their stakeholder engagement process, taking successful first steps. The Romanian Targu Frumos, for instance, historically more prone to top-down decision making, is learning to involve their stakeholders in a more participatory way in their ongoing plans for re-greening public spaces. A perfect example are the plans of the authorities to cooperate with the local university on co-creating the new designs and including the citizens in these discussions. The city's authorities have been actively participating in transnational URBACT activities, with the mayor himself visiting a fellow partner city in Spain, Murcia, to learn from their urban transformation experiences, while sharing their own.

Once the target impact vision is defined and the theory of change to support it is sound and reflects broad stakeholder viewpoints, the next step is to work on impact indicators. These are either quantitative variables or qualitative proofs of successful impact delivery. The challenge lies in getting the right mix of numbers and stories that, together, would reliably illustrate the social impact attributable to a specific urban regeneration project.

Interestingly, larger scopes of urban regeneration, such as those covering a specific district, city centre, or even a whole city, often allow for easier-to-design sets of impact indicators. This is because, typically, larger projects justify broader impact studies and larger indicator sets, as well as because they can benefit from the already available city-wide data.

As an illustration, the ambition to regenerate the whole of Mértola, combined with the political will to approach social impact measurement in a highly professional manner, is a great opportunity to measure a wide array of impact indicators, from basic socio-economic statistics such as population growth and safety levels, to the use of public transport and tracking the quality of housing. With a small population, sampling can be relatively easy, as the whole town can be covered with low-cost surveys, meters, or even sensors. It can also be feasible to include qualitative indicators by running door-to-door surveys or collecting in-depth input from in-person gatherings.

In another example, the Spanish Murcia, which is undergoing an ambitious process of linking the two halves of the city together after they have been divided by both a river and a rail track for years, can boast an already impressive list of indicators being tracked on a city level. It is more a matter of refining them for impact measurement purposes and complementing them with more qualitative metrics than a question of putting in place a whole new impact measurement system. Cities like Murcia that already benefit from large-scale basic data collection mechanisms have the opportunity to now focus on more targeted impact questions. More subtle indicators, such as the levels of citizens' pride to be from the city, the measures of social cohesion, the feelings of belonging, or the metrics of strong community, could be the next step in impact measurement in such instances.

Conversely, more limited regeneration projects, even in larger cities, often face more challenges in their impact measurement design. For instance, in Hannut, where the regeneration of a business district is in the planning stages, an effective impact measurement approach will need to combine city-wide indicators with building- or district-level impact tracking. It will also make it more challenging to attribute any measurable impact to the specific urban regeneration project in question. Commendably, there is high ambition to make social impact measurement a standard element of any regeneration project in the city. If this attempt is successful, it could help different project owners leverage the same sets of data, build synergies across different impact measurement initiatives, and contribute to a larger impact narrative in Hannut.

In Targu Frumos, a specific project of freeing the space of old garages and storage lockers and turning them into multi-purpose green spaces for the community will require designing hyper-local indicators that are able to track the impact of the intervention on the spot. Typically, a project like this will be able to rely less on national or even city-wide data and will instead require in situ data collection to understand how the use of the new facilities is influencing people's levels of loneliness, socialising habits, mental health, community cohesion, or similar indicators. These types of questions require not only a very meticulous design of data collection instruments (such as enthnographic observation guides or in-person semi-structure interview guidelines) and highly trained staff, but they also face challenges in terms of correct attribution, accounting for the drop-off effects, or tracking of the potential negative impacts. Also in this case, the city is fortunate to have a dedicated management team that is hoping to undertake collaboration with a local university to ensure the highest scientific standards of the study.

Successful social impact measurement of urban regeneration is a balanced mix of science, art, and political will. Time will tell how the ten European cities from the U.R. Impact network fare on this journey. One thing is certain: each of the cities has a dedicated and increasingly well-qualified team in place, eager to make their city's regeneration efforts a source of true positive impact for their communities. That's a very promising start to any impact measurement endeavour!