Remote work in Europe- from exception to everyday practice

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telework in most EU countries was relatively rare. Eurofound estimates that the share of workers teleworking “usually or sometimes” in the EU was around 11 percent in 2019, up from fewer than 8 percent in 2008. The pandemic triggered a rapid shift: by 2021 around 22 percent of employees were working from home, and more than 44 million people in the EU teleworked at least sometimes.[1]

Recent data suggest that remote work has stabilised at a higher level rather than reverting to pre-pandemic norms. In 2023, an estimated 22 percent of employed people aged 15–64 in the EU worked from home at least occasionally, compared with roughly 14 percent in 2019. Teleworking numbers effectively doubled between 2019 and 2021, reaching about 41.7 million workers.

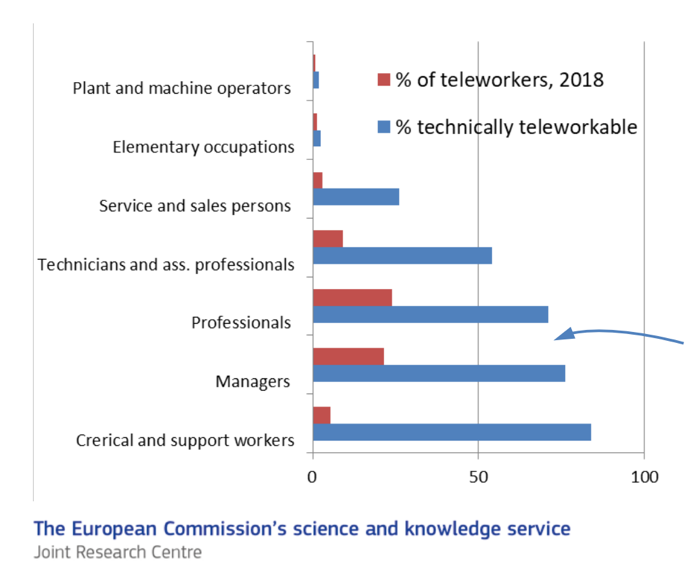

At the same time, the potential for remote work is even larger. A study by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre estimates that around 37 percent of EU-27 employees are in occupations that can technically be carried out from home, with most countries falling between 35 and 41 percent.[2]In other words, the number of remote workers we see today is still below the technical ceiling, and further growth is likely.

Figure 1: Teleworkability and actual teleworking, EU27, share of employment % by broad occupation group

Figure 1: Teleworkability and actual teleworking, EU27, share of employment % by broad occupation group

Defining the remote worker

European policy documents and labour statistics use several overlapping concepts: “telework”, “remote work”, “hybrid work”, “home-based work”, “digital nomads”. For city strategies, it is useful to clarify how these relate.

Telework in the EU context usually refers to work performed away from the employer’s premises, using information and communication technologies, on a regular basis. Eurofound and EU labour legislation often use this term for work done from home or another fixed location.

Remote work is a broader concept. It covers any work arrangement in which tasks are performed away from the employer’s primary workplace, with digital tools as a key enabler. Remote workers may work from home, from a coworking space, from a secondary residence, or from another city or country.

Within remote work, it is helpful to distinguish:

Fully remote workers who rarely visit a central office and can choose where they live.

Hybrid workers who combine office and remote locations (for example two days at home, three days in the office).

Mobile or multi-local workers, who spend extended periods in different locations, including so-called digital nomads.

The Remote-IT network looked beyond one narrow category. It considered three main groups:

Municipal employees working remotely or in hybrid models.

Local workers in the private sector whose employers allow remote or flexible work.

Remote workers and digital nomads arriving from other cities or countries and plugging into the local economy.

These groups overlap but have different implications for policy. A civil servant working from home three days a week, an IT professional who has moved from a capital city to a smaller town, and a designer who spends three months in a city under a digital nomad visa all count as remote workers, yet their needs, rights and impacts are not the same.

Who is working remotely today? A socio-economic profile

Sectors and occupations

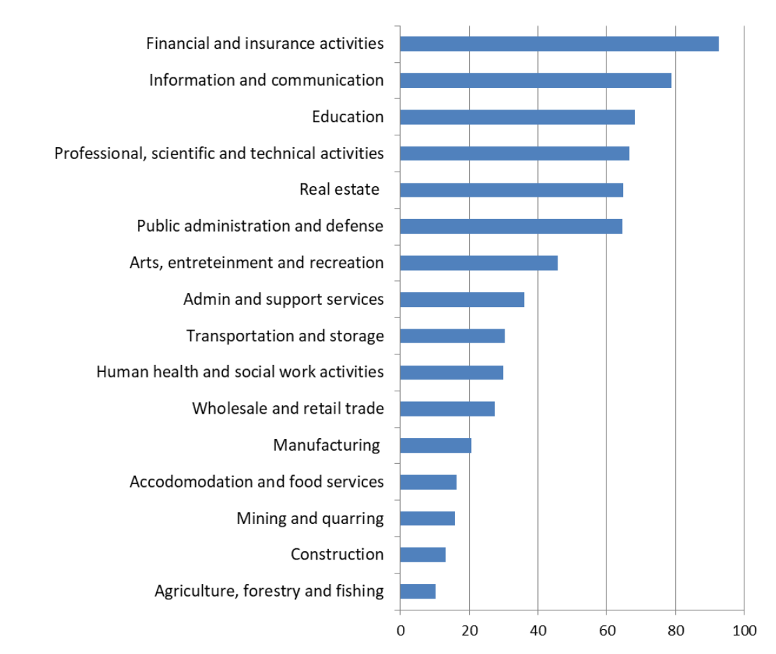

Not all jobs can be done remotely. The Joint Research Centre’s assessment of “teleworkable” occupations found that remote work potential is highest in financial and insurance activities, information and communication, education and professional, scientific and technical activities, real estates and public administration and defense. Workers in hospitality, manufacturing, retail, care and many public-facing services have far fewer opportunities to work from home.

Figure 2: Teleworkability, EU27, % of employment by sector, Joint Research Centre

As a result, remote workers are concentrated in higher-skilled occupations. OECD analysis shows that managers, professionals and associate professionals account for the majority of remote workers in Europe.[3] This aligns with what Remote-IT cities observe locally: a high representation of IT, creative industries, higher education, consulting and other knowledge-intensive services among people who work remotely, whether they are local residents or incoming nomads.

Education and income

Remote workers are, on average, more highly educated and better paid than non-remote workers. Studies across EU countries show that remote work is more common among workers with tertiary education and in high-wage sectors. This does not mean all remote workers are well-off, many freelancers face income instability, but it does mean that the benefits of remote work are unevenly distributed.[4]

For cities, this inequality has two sides. On the one hand, attracting remote workers can bring additional disposable income, tax revenues and demand for local services. On the other hand, if left unmanaged, it can put pressure on housing affordability and deepen divides between highly mobile professionals and residents in less teleworkable sectors.

Gender and age

Gender differences in telework are relatively small but notable. Eurofound data suggest that slightly more women than men telework in Europe, reflecting both sectoral patterns and care responsibilities. Remote work can offer greater flexibility for parents and carers, but it can also reinforce unequal divisions of unpaid care work if not accompanied by supportive policies.

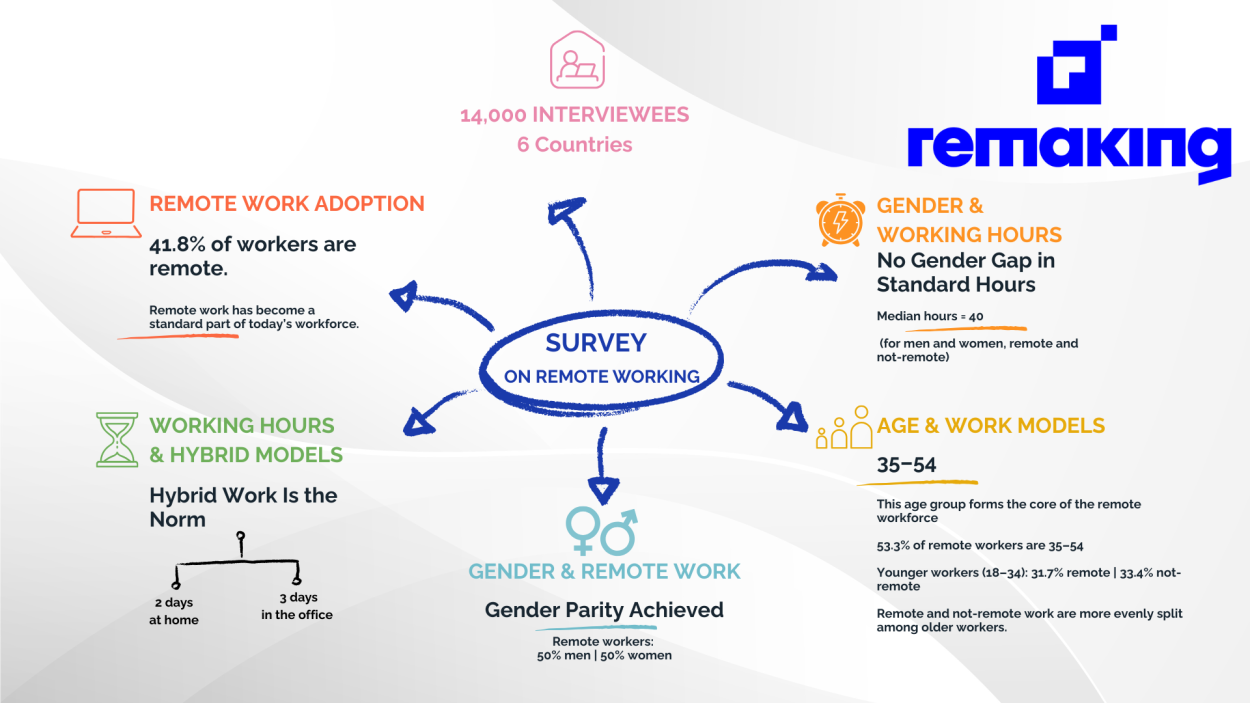

Age patterns show that remote work is most common among mid-career workers. Survey data from European project Remaking[5] indicate that workers aged 35–54 are over-represented among remote workers compared with younger workers, who remain slightly more concentrated in on-site roles. For city strategies, this means that the “typical” remote worker is often not a recent graduate backpacking with a laptop, but a professional with established skills, often with family responsibilities.

Figure 3: Infographic with survey data on remote working, taken from Remaking project

Learning and skills

Remote workers are more likely to participate in non-formal learning, such as courses, seminars and workshops, compared with those who do not work remotely. Cedefop’s analysis[6] links remote work with higher rates of continuous training and skills development. This reinforces remote workers’ role as a potential knowledge resource for local ecosystems, especially when cities create spaces for interaction with students, entrepreneurs and local organisations.

Beyond the stereotype- digital nomads and other mobile remote workers

Media narratives often associate remote work with “digital nomads” - people who combine location-independent work with frequent travel. This group was important for many Remote-IT cities, particularly those with strong tourism sectors, but it represented only part of the remote-worker landscape.

Digital nomads are typically aged between 25 and 44, and a significant share come from high-income countries. In some surveys, roughly four in five nomads fall into this age group. However, there is growing diversity: remote work families travelling with children, older workers combining part-time remote work with periods of “semi-retirement” abroad, and people from emerging economies seeking opportunities in European labour markets.

From a city perspective, it is useful to situate digital nomads within a broader range of mobility:

Returnees and diaspora remote workers – people who grew up in the city or region, left to study, work or other reasons, and then return (permanently or part-time) thanks to remote work opportunities.

Seasonal and “slow” nomads – people who spend several months in a place, often returning annually, sometimes with families.

Short-stay nomads and remote tourists – people whose stay is measured in weeks rather than months and whose connection to the local community is weaker.

Remote-IT partner cities see examples of all of these profiles. For instance, coastal and island partners like Dubrovnik, Heraklion, Brindisi and Câmara de Lobos encounter both seasonal nomads and longer-term residents who choose a “remote-first” lifestyle in attractive environments. Inland cities such as Murcia or Bucharest District 6 are looking at remote workers as part of broader strategies to diversify their economies and retain talent beyond the capital city.

Recognising this spectrum helps cities tailor policies: the needs of a family living year-round in a neighbourhood are different from those of a freelancer spending two months in a coworking hub.

The geography of remote work- who benefits where?

Remote work is not only socially selective; it is also spatially uneven. A study on the new geography of remote jobs in Europe shows that the share of remote workers increased from about 5.4 percent in 2019 to 14 percent in 2021, but this growth was concentrated in larger metropolitan and knowledge-intensive regions. Capital cities and major urban centres often have both a higher share of teleworkable jobs and better digital infrastructure.[7]

At the same time, smaller and medium-sized cities like most Remote-IT partners see remote work as a chance to rebalance territorial development. If jobs can be done from anywhere, why not from Brindisi, Dubrovnik or Heraklion rather than only from national capitals? In these contexts, remote work becomes a tool for:

retaining local graduates who previously felt compelled to move away;

attracting new residents who value affordability, quality of life and proximity to nature;

enabling diaspora members to maintain stronger ties or even return permanently.

However, this potential is not automatic. Without appropriate housing policies, mobility options, and community infrastructure, remote work can intensify housing shortages, gentrification or seasonal imbalances- issues that Remote-IT cities, particularly tourism-intensive ones, are actively struggling with.

What all this means for city strategies

Understanding who remote workers are is only the first step. The real question for city leaders is how to integrate remote work into broader development strategies in a way that is socially inclusive, environmentally sustainable and economically resilient.

Below are key implications that cut across Remote-IT partners’ experiences and wider European evidence. (Other articles in this Playbook will explore each theme in more operational detail.)

Treat remote work as a cross-cutting agenda, not a niche add-on

Remote work touches economic development, housing, mobility, education, tourism, digitalisation and human resources in city administrations. If it is treated solely as a tourism-marketing topic or an HR benefit, important synergies and risks will be missed.

Cities can benefit from:

embedding remote work considerations in strategic documents such as digital strategies, climate plans and economic development strategies;

creating cross-departmental working groups or taskforces, similar to the URBACT Local Groups used in Remote-IT, to ensure coordination.

Segment remote workers and prioritise

Given limited resources, cities cannot design tailored policies for every possible profile. Segmentation helps clarify priorities. For example, a city might decide to:

focus on rooted remotes and emerging locals as key to long-term demographic renewal;

manage passing nomads mainly through tourism policies;

develop specific programmes for diaspora returnees or remote work families.

Remote-IT’s persona and customer-journey tools, described in a later Playbook module, offer practical methods for this segmentation.

Align remote work with inclusion and green transition goals

Remote work interacts with existing inequalities. Higher-skilled workers are more likely to enjoy flexibility, while others remain tied to on-site jobs. At the same time, remote work can reduce commuting emissions but may increase travel-related emissions for highly mobile nomads.

Cities should therefore:

ensure that digital infrastructure, public spaces and services that benefit remote workers also benefit local residents;

consider how housing policies, transport planning and land-use decisions can support both remote workers and other vulnerable groups;

connect remote-work strategies to climate and sustainability goals.

The rise of remote work invites cities to rethink a long-standing assumption that jobs and people are fixed to a single location. Understanding who remote workers are- their sectors, socio-economic profiles, mobility patterns, motivations and constraints, is essential for designing effective strategies. It allows cities to look beyond clichés, to surface both opportunities and risks, and to align remote-work policies with broader goals such as demographic renewal, social inclusion and climate neutrality.

[1] Eurofound (2023), The future of telework and hybrid work, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[2] Milasi, S., Hurley, J., Bisello, M., Gonzales-Vazquez, I., and Fernandez-Macias, E., Who can telework today? The teleworkability of occupations in the EU, European Commission, 2020, JRC121426.

[3] Özgüzel, C., D. Luca and Z. Wei (2023), “The new geography of remote jobs? Evidence from Europe”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 57, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/29f94cd0-en.

[4] Eurofound (2024), Flexible work increases post-pandemic, but not for everyone, article.

[7] Luca, D., Özgüzel, C., & Wei, Z. (2025). The new geography of remote jobs in Europe. Regional Studies, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2024.2352526