When cities and regions talk about mobility, climate action, or inclusion, the focus usually falls on plans, strategies, and technical evidence. These are necessary, but on their own they rarely build understanding, trust, or support for change. Experience from the Beyond the Urban network shows that progress is more likely when cities can clearly explain why they are acting, what they are testing, and how this connects to everyday life. Storytelling is not a communications extra. It is a practical tool that helps cities engage residents, align teams, and transfer ideas between places.

During exchanges between partners, including the APN meeting in Paris, storytelling emerged as a practical way to connect technical work with people’s lived experience. Partners reflected on how narratives, examples, and simple messages helped them explain complex work, engage residents, and support transfer between cities and regions.

From technical solutions to everyday experience

In many rurban (rural to urban) territories, mobility challenges are widely recognised. Car dependency is high, alternatives are fragmented, and residents are often sceptical about change. Several partners found that presenting these challenges only through data or policy language limited engagement. What worked better was starting from situations people already recognise, such as school runs, access to services, or how public space is used, and then linking these experiences back to policy choices.

Kocani

In Kocani, conversations about mobility gained traction when framed around children’s daily journeys to school and the concerns of families, rather than abstract safety indicators. For other cities, the lesson was clear: starting with a shared concern made the policy conversation more accessible and reduced resistance before solutions were even discussed.

Treviso

In Treviso, a temporary car-free day in a central square allowed residents to experience a different use of public space, creating a shared reference point for discussion. By allowing people to experience change rather than imagine it, the intervention created a common reference point that data alone could not provide.

Machico

In Machico (picture above), small improvements to pedestrian routes made sense because they were explained in relation to effort, comfort, and access to everyday destinations in a steep landscape.

These examples show that storytelling helps translate policy objectives into situations that people recognise and care about.

Storytelling as a tool for Implementation

Storytelling as a tool for Implementation

Storytelling also supports implementation. Clear narratives helped teams align departments, explain pilot projects to decision-makers, and justify why small, time-limited tests were worth funding.

Several partners naturally adopted simple narrative structures. They described a familiar situation, identified a concrete problem, explained what was tried, and showed what changed as a result.

In Bram, the focus was not cycling infrastructure in isolation, but how families experienced cycling together through the Vélobus (picture on the wright).

In Santa Maria da Feira, digital mobility tools became meaningful when framed as a response to everyday confusion about services (picture above).

In Szabolcs 05 (picture below), youth-led activities were easier to support because they told a clear story about participation leading to better decisions.

By clarifying purpose and sequence, storytelling helped make experimentation more acceptable and more understandable.

Helping ideas travel between places

One of the strongest values of storytelling lies in transfer. Cities and regions looking for inspiration often struggle to relate to long technical descriptions or complex planning documents. Stories make it easier to see how an idea works in practice and whether it could be adapted elsewhere.

During exchanges in Paris (picture above) with other APNs and throughout the network, partners shared short narratives about school routes, community cycling activities, or intermodal hubs. These stories allowed others to quickly grasp the essence of an action, even before diving into technical details. Storytelling thus acted as a bridge, lowering the barrier to learning and encouraging adaptation rather than replication.

Stories did not replace technical documentation, but they made it easier for others to engage with it.

Choosing the right format

Partners also reflected on how different formats serve different purposes. Written descriptions help explain processes and responsibilities. Visuals and diagrams make systems easier to understand. Short videos and spoken examples convey emotion, context, and motivation.

This understanding influenced how the network shared its results. Alongside written guidance, partners developed a short video that captures voices, places, and experiences from different territories. The video does not aim to explain every action in detail. Instead, it communicates why the work matters and how diverse contexts face similar challenges. Used together, practical tools and storytelling formats reinforce each other and reach wider audiences.

Practical tips for cities and regions

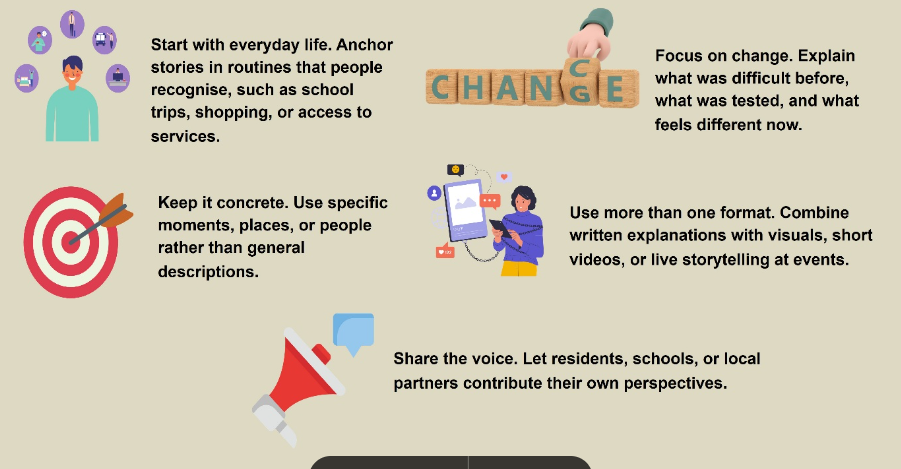

Drawing on the experience of the network and reflections shared in Paris, several practical tips emerge:

Storytelling as part of urban practice

Across the Beyond the Urban network, storytelling became part of everyday urban practice. It helped teams reflect on progress, align stakeholders, and build confidence to experiment. For cities and regions navigating complex transitions, this matters. When mobility is framed as lived experience rather than abstract systems, local actions become easier to understand, easier to adapt, and more likely to travel beyond their place of origin.