In Dunaújváros, an industrial city in Hungary, Lead Partner of the BiodiverCity network (community-based approaches to foster urban biodiversity and nature-based solutions), as well as in Guimarães, Europe’s Green Capital in 2026 (BiodiverCity partner city), two completely different places in Europe, residents are lucky because they can get advice from their Urban Biodiversity Office in such a situation. Advice on why native fruit trees, as well as herbaceous plants, are efficient in attracting pollinators and why it is important to shelter pollinators in urban areas. Their residents can learn that wildflower meadows are also efficient in regulating the local microclimate. They might learn tools they can use to attract birds and bats. They can learn about microhabitats, such as a small pond, which acts as a biodiversity hotspot. And if the neighbours complain about mosquitoes, they can understand that nature is a self-regulatory system: if there is a habitat for mosquitoes, there are also their predators. In such an office, experts can showcase the economic benefits of green walls and rooftops, and most importantly, they can explain to your neighbours that while you create habitats for species in your garden, you make your garden more resilient and do climate action.

We still prefer unsustainable and biologically poor, manicured mown, because we have dramatically lost our connection to nature. We do not know the difference between a primeval forest and a tree plantation, we do not understand the importance of wetlands and peatlands in carbon sequestration, and we do not realise how forests and wetlands create rain. In the shadow of inevitable climate change and rapid urbanism, we must get our connection to nature back, since biodiversity supports everything in nature that is essential to survival: food, clean water, medicine, clothing, climate, and economic growth (yes, even that: according to the World Bank, over half of the global GDP is directly dependent on nature).

This connection plays a key role when we intend to increase the size and quality of urban green spaces, as well as natural habitats and protected areas in and outside of the cities, to combat the negative effects of the ecological crisis. This connection is deeply rooted in cultural values, attitudes and norms; therefore, it is more efficient to talk about plants, animals and water than using technical terms. It is more efficient to use Jane Goodall's “Hope in Action” approach! Nature provides not only unbelievable benefits for our physical and mental health, but also cheap and aesthetic solutions to develop our cities and reshape our landscapes, to make the long-desired paradigm shift in all areas of economic life. So, what are we waiting for?

The added value of exchange and learning

Between 2023 and 2025, the 10 BiodiverCity partner cities (Cieza, Dunaújváros, Guimarães, Limerick, Poljčane, Sarajevo, 's-Hertogenbosch/Den Bosch, Siena, Veszprém and Vratsa) studied and worked on the different aspects of urban biodiversity as well as nature-based solutions (NbS) – two sides of the same coin -, and based on intensive transnational exchange and learning, they prepared integrated action plans (IAP) together with local stakeholders to tackle the most pressing local issues.

How did they empower residents to plan NbS with the help of biodiversity?

Urban biodiversity as such is a relatively new topic in the EU policy arena. No surprise that intensive exchange and learning activities inspired partners, and the most interesting initiatives are indeed embedded in several action plans. Veszprém’s climate-adaptive grassland management clearly boosted Dunaújváros, Den Bosch, Poljčane and Limerick, for example. Another attractive initiative was Guimarães’s focus on biodiversity within urban development, manifested in a dedicated office (Landscape Laboratory) and the so-called biodiversity officer in Limerick, which has been created within a national framework. By using additional funds (LIFE) and inspired by the BiodiverCity network, Dunaújváros has already opened a Biodiversity Office, while Veszprém, among other partner cities, laid down its plans. Bioblitz, as a special engagement and citizen science technique focusing on biodiversity in urban areas, introduced by Siena and Guimarães, also appears in many IAPs, just like Limerick’s Natural Play Area and Cieza’s Biophilic City approach (sustainable urban tree management).

Partner cities even jointly worked on nature-based solutions, creating a clear added-value not only for the Slovenian town Poljčane, but indirectly also on the national level in Slovenia – reported mayoress of Poljčane, Petra Vrhovnik. In this case, transnational dialogue reinforced locals’ plans to use willow and woven fences to prevent regular riverbank erosion along the still freely meandering Dravinja river, which area is protected by Natura 2000, and therefore they have not received permission from national authorities so far. The Ministry of Environment of Slovenia has finally applied the above-mentioned techniques as a pilot to decrease invasive alien species on the riverbank at other sections of Dravinja, while Poljčane is now allowed to implement similar structures on several meanders in its territory to control erosion.

Urban biodiversity is sexy!

A common element of final IAPs is to increase urban biodiversity (some specific segments or through a more comprehensive approach) with the active involvement of the community to renew the relationship between people and their environment. The better elaborated IAPs tackle all of this within an inclusive, connected, and resilient urban green network. Cities indeed can do a lot to create shelters for biodiversity as well as to promote a more pro-environmental attitude among their residents, along with urban biodiversity management. Why? Because green space stimulates identity and community spirit efficiently. Access to private gardens, for example, can prompt green consumption and changes in shopping habits towards more environmentally aware purchasing.

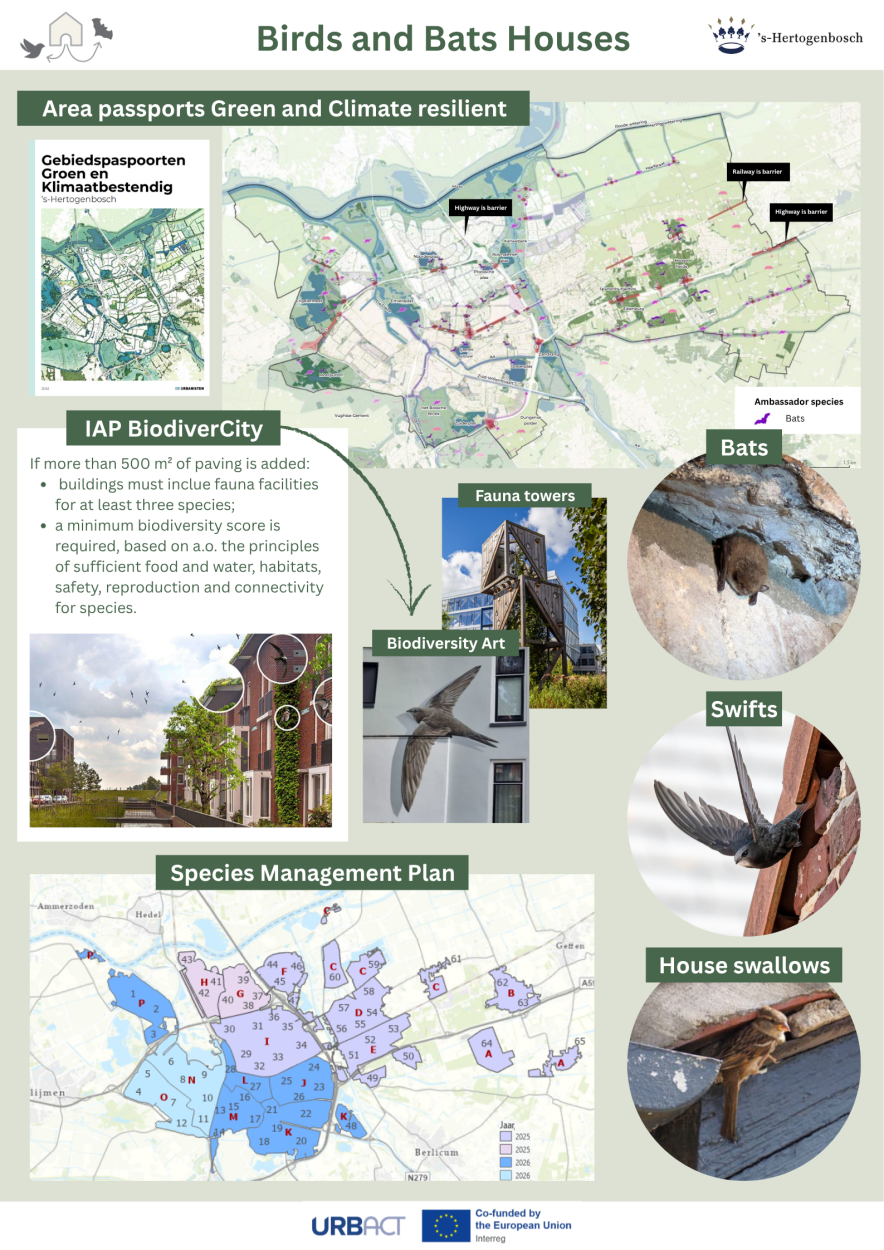

Dunaújváros, for example, will launch a deadwood program, inspired by Veszprém and plans green roofs and green walls. Cieza will create wetlands for amphibians, learnt from Guimarães. Other interesting actions from Cieza are re-naturalisation of schoolyards, increasing tree cover on streets and training workshops for politicians, since efficient green infrastructure needs common, cr oss-departmental understanding. Veszprém is to prepare an integrated municipal water management plan, inspired by Limerick, and continues with urban beekeeping, community composting and rain gardens. Den Bosch will create natural play areas, organise bioblitz events and Jane Jacobs Walks, while Sarajevo will transfer the first green Peace Circle established within the network to other places. Within its IAP, Guimarães concentrates on urban micro-habitats and develops urban green corridors to enhance ecological connectivity, while Siena, among other actions, is keen on education campaigns and continues the EcoSistema Urbano (BiodiverCity Festival tested within the project).

We must give space back to Nature!

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), one-third of the climate mitigation needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement can be provided by NbS. At the same time, the World Economic Forum states (BiodiverCities by 2030) that NbS are 50% cheaper in urban infrastructure than grey infrastructure, yet they received just 0.3% of overall spending on urban infrastructure in 2021. So, we need to raise awareness of all actors about the effectiveness of NbS and lead by example. Nature-based solutions are efficient, cheap, aesthetic, and good for nature - so, what are we waiting for? What is good for nature is good for us, humans. Especially in Europe, where, on the one hand, 81% of EU protected habitats and 63% of EU protected species are in “poor” or “bad” conservation status (2020 ‘State of Nature in the EU’ report), but on the other hand, globally high nature restoration ambitions have been published within the historic Nature Restoration Law.

A drop in an ocean?

Urban areas not only can harbour a high diversity of species, but cities offer unique opportunities for learning and education about a resilient and sustainable future and have a significant potential to boost innovations and governance tools. Not to mention that billions of urban dwellers are at high or extreme risk of environmental disaster. Thus, urban green spaces are beneficial for residents for multiple reasons through the ecosystem services green areas provide.

Of course, BiodiverCity action plans will not save the world. But the biggest added value of them is that many partners not “only” plan various, isolated projects, but also local regulations and the change of maintenance modes as well, creating a significantly more serious impact locally. Among others, revision of green maintenance (Siena, Limerick), expansion of unmown zones and planting of native plants (Dunaújváros), development of a local regulation requiring permeable solutions in new public constructions and renovations (Guimarães), approval of the municipal biodiversity ordinance (Cieza), and mandatory nature-inclusive constructions (Den Bosch) are all planned.

Although most IAPs will not be officially approved by city councils, most of them indeed found their place in the often very dense policy landscape of the given cities. Most IAPs were presented to the city leaders, some of them were disseminated in schools, and somewhere, a specific website was created dedicated to the plan. Many of them will also be embedded into higher policies or strategies when regular review of them allows it (i.e. in Limerick, the Biodiversity Action Plan will be reviewed soon, and the IAP will be embedded; in Veszprém, the IAP will strengthen the sustainable urban development plan and the green surface development plan to be reviewed soon). The effective work of partner cities is also manifested in such success stories as in Cieza, which will receive significant ERDF funding to continue its frontrunner work to make the city more biophilic. This huge success is partly due to their participation in the network – a drop in the ocean?!

Urban biodiversity offices to everyone!

Rockstrom et al. (2009) identified nine so-called planetary boundaries (beyond which anthropogenic change will put the Earth system outside a safe operating space for humanity), and biodiversity loss is the single boundary where current extinction rates put the Earth system furthest outside the safe operating space. Decision-makers have finally understood that the different elements of the ecological crisis, as the most pressing issue facing humanity today, must be tackled together if we are to secure a viable future on this planet.

Without understanding how nature works, and without giving some space back to nature in and outside cities, we cannot efficiently combat the negative effects of the ecological crisis. And yes, every spot accounts, even a small private garden, especially since very often the most urban green area is owned privately.

So, welcome to the Urban Biodiversity Office! This is the title of the guidebook, prepared by the BiodiverCity network (An Urban Biodiversity Guidebook for cities to transform their relationship with nature). The guidebook highlights those thematic fields where cities can enhance urban biodiversity, enabling them to put biodiversity as a core organising principle of urban planning. This guidebook is for everyone: residents and city practitioners as well. From sustainable urban tree management and wildflower meadows through nature-inclusive buildings and constructed wetlands to bird-friendly policies and community engagement, this guidebook highlights those thematic fields where cities can enhance urban biodiversity, enabling them to put biodiversity as a core organising principle of urban planning.