How can cities create effective programmes for promoting enterprise and entrepreneurship? How should cities respond to some of the structural changes currently taking place in the business start-up market?

With an estimated 100 million businesses starting up across the globe annually, an increasing number adopting innovative business models (built, for example, around the ‘sharing’ or ‘gig’ economy) and the number of sole-trader businesses increasing annually, this is clearly a highly active and increasingly disruptive marketplace.

Among all URBACT Good Practices, Glasgow (co-operative entrepreneurship), Bologna (creative entrepreneurship), Piraeus (marine sector based entrepreneurship); and Barcelona (inclusive entrepreneurship) provide interesting examples on how to create impactful city-wide ‘ecosystems’ for promoting enterprise and entrepreneurship.

What are ‘entrepreneurship eco-systems’?

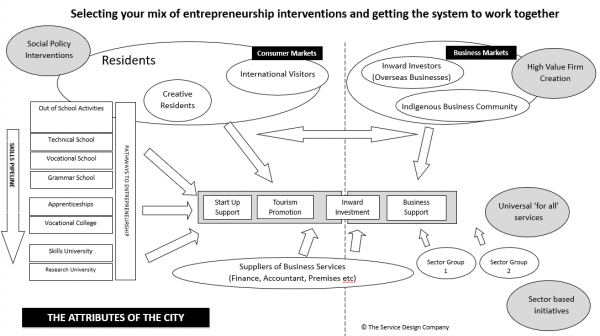

‘Entrepreneurship eco-systems’ are essentially the ‘building blocks’ for stimulating entrepreneurship which can be adapted in a city to create a stronger or lesser environment for fostering entrepreneurship.

The concept of places needing to think about such eco-systems has been widely developed by Dan Isenberg, the founding executive director of the Babson Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Project and a former professor at the Harvard Business School.

In his Forbes Magazine article, Isenberg suggests that the place-based ‘entrepreneurial eco-systems’ are made up of the culture of the city; the business enabling policies; the strength of local leadership; the availability of suitable finance for business; the quality of human capital; venture-friendly markets; and a range of institutional and infrastructural support.

Why ‘entrepreneurship eco-systems’ are becoming increasingly important

Wider structural changes within society are blurring the traditional boundaries between employment, enterprise and entrepreneurship.

Shifts in technology, connectivity and the wants and expectations of both employers and employees are creating significant changes to the nature of work and the formal and informal contracts that exist between employer and worker (see, for example, Preparing for the Future of Work, World Economic Forum, 2016).

These changes are giving rise to a whole new generation of freelancers.

Overlay on top of these changes some of the wider shifts in society – including slow wage growth, the increasing high-cost of living in some of the world’s major Cities and the growth in the freelancer community – and it’s easy to see how these changes can support the future growth of some of Europe’s smaller and more peripheral cities (for an example, see The Four Trends That Will Change the Way We Work By 2021, Fast Company, 2015).

These changes are also giving rise to a whole new vocabulary. Phrases like the ‘independent workforce’ have emerged to describe the range of different contracting relationships that individuals can have with business. The number of solo-entrepreneurs - or ‘solopreneurs’ – is on the rise. Phrases like side-giggers have emerged to describe individuals who work in the sharing economy, whilst also holding down a traditional job, on a part-time basis.

Udacity, the innovative online education provider that works in partnership with leading tech companies like Google, AT&T, and Facebook has coined the term ‘nano-degree’ and ‘nano-job’ to describe the short-term nature of individuals learning needs and the short-term nature of some work assignments in the tech industry.

Rethinking traditional employment, enterprise and entrepreneurship programmes is necessary

With the blurring of lines between employment, enterprise and entrepreneurship, many forward-thinking cities are having to re-think the traditional employability and entrepreneurship programmes they have previously provided for their residents.

Employability programmes increasingly need to include more content on enterprise and entrepreneurship, to try and support participants to acquire the skills needed to survive in today’s more complex labour market.

Similarly, Entrepreneurship programmes need to adapt to be better suited to the increasing number of freelancers and sole traders joining their programmes, and to take account of innovative new business models that businesses might adopt. You only have to search for ‘Tools for Solopreneurs’ on the internet to see how fundamentally different their support needs are from more ‘traditional’ businesses.

But the changes needed are much more widespread than that.

Ultimately, because of the changing nature of the relationship between employer and individual, cities also need to try to embed a much deeper culture of enterprise in their entire population, to try and ensure that they are equipped with a more independent, resilient and self-reliant outlook and also possess the necessary problem solving, business and creativity skills needed to survive in this new world of work.

The processes for collaborating with young entrepreneurs has had to become more collaborative and ‘experiential’ than ‘traditional’ start-up programmes – to encompass hackathons, service jams and meet-ups, rather than relying solely on classroom-based training courses and advice sessions.

Tips and Tricks from URBACT Good Practices

The Good Practices of Glasgow (co-operative entrepreneurship), Bologna (creative entrepreneurship), Piraeus (marine sector based entrepreneurship) and Barcelona (inclusive entrepreneurship) have each taken a different approach to business support, which other cities can take inspiration from.

- Establishing a strong ‘generalist’ support system: Barcelona Activa’s Inclusive Entrepreneurship Good Practice offers a ‘universal’ service that is ‘available for all’ in the city which – between 2004 and 2016 - has supported over 100,000 participants, established over 18,000 companies and created over 32,000 jobs. It operates on the basis of being open to everyone and delivers a mix of online, one-to-many and face-to-face support services to anyone looking to start their own business. In addition, they offer specialist support services for particular nice groups they want to encourage, like women entrepreneurs and people from ‘disadvantaged’ backgrounds.

- Stimulating social entrepreneurship: Glasgow’s Co-operative City Good Practice has developed a city-wide approach to co-operative development, which is building new partnerships between public services and local people to foster greater co-design and delivery of local services and giving a wider group of residents of the city a direct experience of running, or being a shareholder in a social enterprise. The scale of the reach that Glasgow’s programme has achieved is impressive, helping local residents think about how social entrepreneurship can support their community to tackle local challenges. Stimulating social entrepreneurship in communities to help people overcome particular challenges can help individuals gain the experience of running a business, without necessarily having to carry all of the risk

(because they are working in partnership with others).

- Supporting creative & cultural industries: Bologna’s IncrediBOL! Creative Innovation Good Practice programme provides a range of tailored support to creative businesses to support them to start up, has received over 500 applications over the last 7 years, supported over 80 businesses, which have a survival rate of 81%. The methodology for delivering support to businesses that apply to the programme is through a widely publicised business plan competition, which has been particularly successful in stimulating creative business ideas from the market, and investing in successful projects which have built the cultural fabric of the city (further building Bologna’s reputation as a cultural hotspot and attracting more creative talent).

- Building on your cities sector strengths and strategic assets: Piraeus’ Blue Growth Good Practice is a programme, which seeks to stimulate the growth of innovation and entrepreneurship in the marine sector in Piraeus. It seeks to strengthen and build upon some of the sectoral specialisms and strategic (topographic) assets of the city. As a sector based innovation programme, it also works around a business plan competition, supporting successful applicants to start-up.

The four Good Practices also share a number of key characteristics, that make them stand out as Good Practice entrepreneurship programmes, namely;

- Their high levels of awareness / deep market reach: All of these programmes have managed to reach deeply into their target communities and create a high level of awareness and interest in their programmes, inspiring and making possible the aspirations of fledgling entrepreneurs. Achieving high-levels of awareness and market reach is important to drive up demand for entrepreneurship and help people understand where they can get support.

- Their approach to supporting entrepreneurs to grow their business. All of these programmes offer tailored and bespoke support to the people that go through their programmes, connecting them to the specialist support they need to succeed and/or stimulating other important components of the eco-system of support, to ensure aspiring entrepreneurs have access to the help they need to grow their business;

- Their work on stimulating a strong enterprise culture in their city. All 4 Good Practices also focus on trying to stimulate a change in the enterprise culture of their cities, by working in partnership with a range of stakeholders and agencies in their cities to widely promote the benefits of entrepreneurship.

Creating successful entrepreneurial eco-systems requires a whole-system approach

What these four Good Practices demonstrate is how creating a widespread change in the enterprise culture of a city can be a complex and challenging task, that requires strong leadership from city administrations, highly effective partnerships and the stimulation of crowd actions through an ‘ecosystem’ approach (for an explanation of eco-system thinking, see ‘What I Learned from Trying to Innovate at the New York Times’, John Geraci, April 2016)

A city cannot just focus on delivering one or two great entrepreneurship programmes targeted on a few niche sectors of the community, but needs to ‘conduct’ the market like the conductor in an orchestra - to incentivise behaviour change amongst communities, individuals, agencies, influencers and sub-cultures, to try and achieve an overall change in the macro-culture of the city.

In addition to considering the whole-system, it is also important to think about the way different programmes incentivise people to think about starting their own business and how these programmes work together as part of a coherent customer proposition.

In adopting the approach used by the URBACT Good Practices, other cities can create powerful support ‘systems’, which could work together to inspire and make possible the aspirations of their entrepreneurial residents.