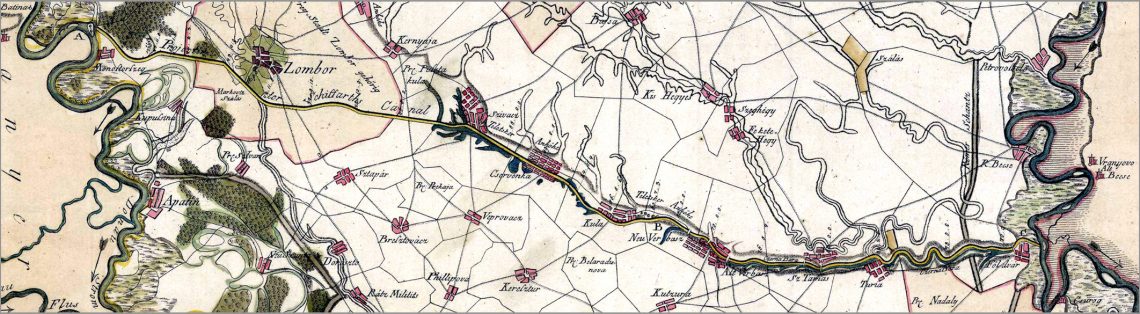

“Hydro Heritage Cities” is a project of the EU URBACT Programme in which the city of Sombor and four other European partner cities are introduced to the experience of the Chalandri, Greece, in revitalising the Roman aqueduct and its inclusion in modern life. Then, similar activities are carried out on local examples of hydro-heritage. Sombor chose the Great Bačka Canal, which has greatly influenced the identity of the city. The time has come to approach the canal in a new way. In the mid-18th century, the first ideas about digging a canal to connect the Danube and the Tisa appeared. However, the project and construction only took place at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, according to the design of József and Gabriel Kis. At that time, it was the largest construction project in Europe, with 2,000-4,000 workers constantly working on it. How difficult it was is also evident by the songs from that period, where the people of Sombor generally had a negative view on the canal.

Map of the Franz Canal (Great Bačka Canal), designed by József & Gabriel Kis, end of the 18thc. (source www.ravnoplov.rs; Milan Stepanović)

When it was opened in 1802, the canal fuelled the rapid development of Sombor due to the trade that took place through it. It should be noted that at that time there was no railway, and the roads were gravel ones. Grain, lumber, wine, tobacco, and food supplies were transported on it on more than a thousand ships per year, a total of about 70-80 thousand tons of goods. There were ideas and projects to dig another canal through the city centre, but these aspirations had never been realised.

As the Danube changed its course, a branch from the Danube to Bački Monoštor was dug in the mid-19th century, with the first concrete gate-lock in Europe according to the design of the imperial engineer Johann Mihalik. It was also the first example of underwater concreting in the world!

The importance of the canal declined somewhat with the construction of the railway in 1869, but it was still the cheapest way to transport large quantities of goods. In 1870, the canal was given under concession for a period of 75 years to the London joint-stock company “Wythes & Longridge”. The canal was renovated under the leadership of István Tir, who was also the constructor of the Corinth Canal in Greece and a close friend and collaborator of the constructor of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand Lesseps. In the next five years, extensive work was carried out (the canal was deepened), and a new water-supply canal was built. This undertaking represented the largest investment of English capital in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918-1945) and the concession expired in 1945.

Bezdan Gate Lock – the beginning of the Great Bačka Canal near the Danube in 1904 (source www.ravnoplov.rs; Milan Stepanović)

During the interwar period, industrial plants sprang up along the canal itself: sugar mills in Sivac, Crvenka and Vrbas, a cloth factory in Kula, many hemp factories and mills. Water from the canal was used to irrigate large areas of arable land, and also to drain water from surrounding estates. The Great Bačka Canal was nationalized in 1945, and after the great flood of the Danube in 1956, it was deepened in the section between Bezdan and Sombor.

With the development of other modes of transport, traffic on the Great Bačka Canal has almost died out over the last fifty years. The canal is extremely polluted in its middle section, making it the most polluted waterway in Europe. The favourable circumstances are that the Bezdan lock was decommissioned in 1995 and that there is no industrial plant between the Danube and Sombor, so its upper section in the Sombor Area has been declared an ecological corridor, with clean water and protected plant and animal species.

The history of the Great Bačka Canal is incredible. Initially the most important transport corridor, originally intended for the transport of goods and drainage. Then modernised and extended to play a key role in the first wave of industrialisation. With the construction of the railway and later roads, the canal completely lost its importance. In the meantime, Serbia, in line with climate change adaptation measures, has adopted a series of strategic documents at the national and provincial levels, which emphasise the importance of preserving the natural and cultural values of the canal, as a very important potential for ecological tourism – the so-called “green-blue infrastructure”.

The Grand Bačka Canal today. Photo by Dragana Siljanovic Kozoderovic.

The main challenge for Sombor is to create a strategy for the further development of the Grand Bačka Canal in this project. The main goal is that canal finally becomes an inseparable part of the city, connected to its lush greenery and rich cultural heritage. Following the example of the Canal du Midi in France, and using methods implemented by the team of the main project partner from Greece, this will be achieved by laying a cycle and walking path along the canal, accompanied by greenery with permanent tree rows. In addition, a specific option would be developed to use the canal water to irrigate the thousands of trees for which Sombor is famous, in order for the city to successfully cope with obvious climate changes. The city must develop this strategy with citizens and local partners from the public, private and civil sectors in the fields of culture, tourism, sports, transport, water management, etc. The intention is to form a foundation from which the measures prescribed by the strategy would be implemented in the future. The Sombor strategy could serve as an example for the entire Vojvodina with its almost 1000 km of canal system. For over two centuries, Vojvodina's canals have proven to be a significant resource for solving ongoing challenges. This is still visible today, but it also requires strengthening the general awareness of their importance in economic, social, environmental and cultural terms.