“So, what shall we do about it?”

Back in 2018, three people — a water engineer, a historian, and a city councillor — sat in a busy Halandri café at the outskirts of Athens, discussing the forgotten Hadrian Aqueduct, a 2,000-year-old marvel buried beneath the streets. Giorgos Sachinis from EYDAP wanted to celebrate the aqueduct’s waters, while Nassy Siafaka from the Halandri Oral History Group aimed to collect local memories. Sitting across the table from them, city councillor Kostas Gerolymatos saw an opportunity to reconnect the aqueduct with Halandri’s cultural identity.

“We make it visible,” they agreed. “And we give it a new life.”

That simple plan — scribbled on the back of a napkin — became the seed of a project that would transform the aqueduct into a symbol of culture, sustainability, and community.

The hard mission of making invisible hydro-heritage visible

Structured with a public-private partnership, the original idea became Cultural H.ID.R.A.N.T., an innovative approach of the city of Halandri (pop. 77.102) that was later approved under the EU’s Urban Innovative Actions (UIA) programme. This ambitious mission required blending technical innovation, environmental sustainability, and social engagement.

[ The Hadrian aqueduct in Halandri. Photo courtesy: EYDAP ]

At the heart of the project is the creation of a non-potable water network that taps into the aqueduct’s underground flow. As part of Halandri’s climate resilience strategy, this network now supplies homes, parks, and green spaces with water for irrigation and other non-drinking purposes. “The aqueduct intervention was small compared to other works that we normally do at EYDAP,” explains Giorgos Sachinis. “a small thing with a big purpose: to change behaviours about water consumption, to help us shape our approach and regulation on non-potable water networks."

Recognising that parts of the city were not directly connected to the network, through the project, the municipality has introduced water trucks to expand access, a service operated by a Roma social cooperative, creating environmental and social impact by concurrently empowering a marginalised group.

The Hadrian Community of Chalandri, a legal association established as a result of the project, now ensures the long-term governance of the aqueduct. Bringing together the municipality, technical experts, citizens, environmental groups, and social cooperatives, it balances public oversight with community-driven initiatives. “This community is key to the project's future,” explains Kostas Gerolymatos Halandri City Councillor “it’s a governance model that combines public responsibility technical expertise, and social engagement — ensuring the aqueduct will remain a living resource and a commons.”

The birth of a European Innovation Network

Strong with the results of Cultural H.ID.R.A.N.T., Halandri is now leading the Innovative Transfer Hydro-Heritage Cities Network, bringing together five European cities — Elche (Spain, pop. 238.293), Roeselare (Belgium, pop. 66.262), Rome (Italy, pop. 2.748.641), Serpa (Portugal, pop. 13.731), and Sombor (Serbia, pop. 41.814) — to explore how hydro-heritage can inspire urban innovation. While each city faces unique challenges, they share a common ambition: to connect their water heritage with sustainable urban development.

For example, in Elche, the UNESCO-listed Palmeral groves currently rely on potable water. Faced with growing drought risks, the city aims to adapt Halandri’s idea of creating a non-potable water network by restoring the ancient function of the historic canals that once irrigated the groves, preserving this iconic heritage while promoting sustainable water management and encouraging sustainable tourism.

Participation at the core

While the Hadrian aqueduct’s revival has been technical in nature, its success has heavily depended on social engagement. Schools have been crucial in involving the wider community. “Our goal wasn’t just to build infrastructure… we wanted people to feel connected to it.” says Sofia Tsadari from Commonspace Co-op, one of the project’s partners. This approach paid off. Students co-designed water tanks stickers, created educational materials, and participated in workshops that explained the aqueduct’s historical and environmental significance. Children’s engagement drew in parents, teachers, and residents, forming an engaged community.

[ Talking about the aqueduct with the Halandri citizens. Photo courtesy: Cultural H.ID.RA.N.T. ]

The Halandri Oral History Group has worked incessantly to reconnect the aqueduct to the city’s identity. Residents shared memories of the aqueduct’s role in irrigation, community life, and even as wartime shelter. “We knew that bringing the aqueduct back to life meant reconnecting it to people’s memories.” explains Nassy Siafaka. These stories were brought to life through “Water Walks,” guided tours that retrace the aqueduct’s underground route. “These walks were powerful,” Nassy adds “people weren’t just hearing about the aqueduct — they were experiencing its presence beneath their feet.”

Halandri’s participatory approach is now inspiring other cities to place citizens at the heart of water heritage initiatives. In Rome, the city plans to involve the local community in regenerating the Orangery of San Sisto, a greenhouse recently refurbished, taking inspiration from Halandri’s co-design work with schools and residents. “Hydro-Heritage Cities can be the push to finally start taking into account both environmental sustainability and citizen engagement when it comes to decide how to use the forgotten heritage gems that every city has.” declares Sabrina Alfonsi, Councillor for Agriculture, Environment and Waste Cycle of the City of Rome. In Sombor, the Great Bačka canal is set to become a focal point in the city’s development strategy, linking industrial heritage with sustainable tourism. This canal is far from invisible, however, "The people of Sombor are not familiar enough with our Great Bačka Canal.” affirms Tamaš Kanižai, Member of the City Council “With this project, we hope that the canal area with all its industrial and natural heritage … becomes an attractive urban place for our citizens.” Inspired by Halandri’s governance model, Sombor aims to build a stronger framework that combines heritage preservation with long-term urban planning. “Innovative ideas that we will come up together with our members of the ULG group can significantly contribute to embrace these aspirations.” Tamaš concludes.

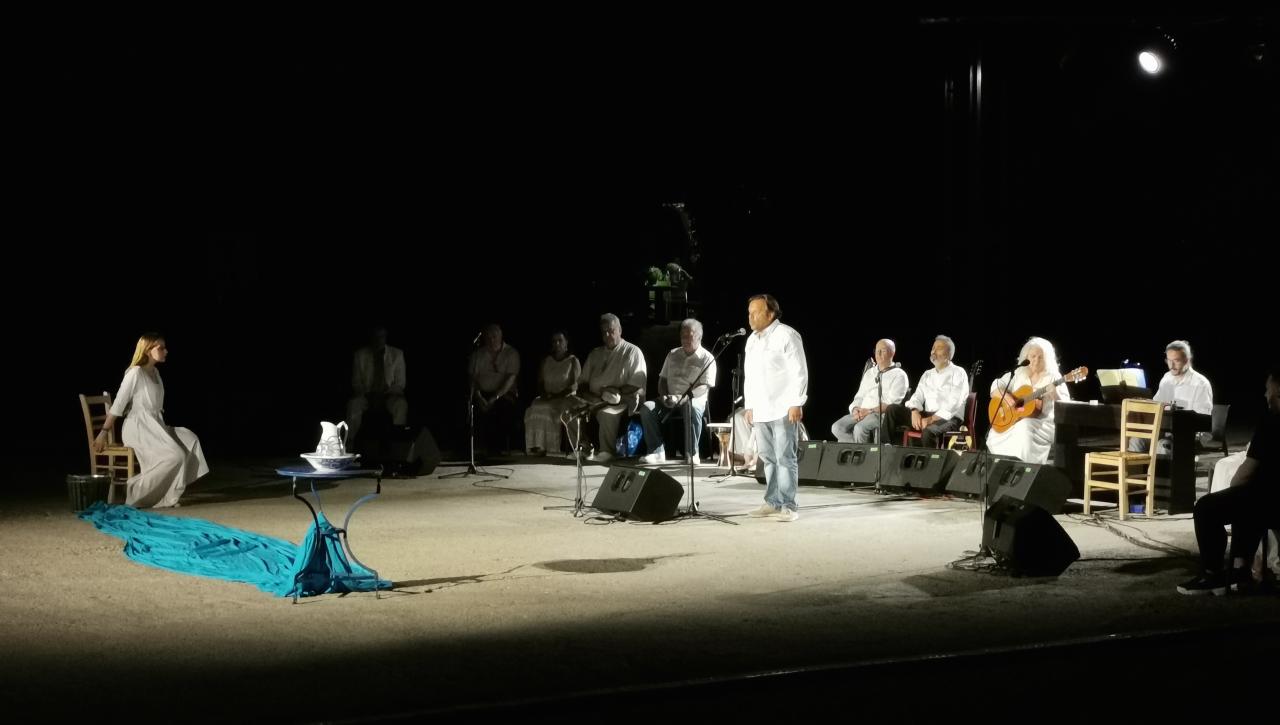

[ Performance at the 2021 HIDRANT festival. Photo: Themis Gion ]

Celebrating water through culture

The HIDRANT Festival has been a defining moment for the project. Through art, performances, and storytelling, residents reconnected with the aqueduct and its cultural significance. “That’s when it clicked,” recalls one performer “The aqueduct wasn’t just a relic… it was ours, part of our current story.” The festival has since become an annual event, spread across the city.

Roeselare’s covered Mandel River and canals are largely forgotten by residents. Drawing from Halandri’s artistic methods, the city aims to reconnect citizens with these hidden waterways using cultural programming, artistic interventions, and education. By combining creative engagement with the city’s water strategy, the Belgian city hopes to inspire residents to see these invisible networks as valuable cultural and environmental assets again.

Challenges along the way

The journey hasn’t been easy for Halandri. The project faced delays due to technical complexities and procurement challenges. “For many residents, their first encounter with the project wasn’t through meetings or public announcements,” recalls project manager Christos Giovanopoulos. “It was the sight of caterpillars digging around the city.”

Still, despite the hurdles, the project adapted, turning obstacles into opportunities for innovation. The COVID-19 lockdown disrupted engagement efforts. “We couldn’t meet face-to-face, so we had to get creative” recalls Sofia from Commonspace “we launched digital workshops, sent activity kits to families — anything to keep people engaged while we were apart.”

Embracing the digital age

Digital innovation has been introduced to raise awareness about the heritage and water-related environmental issues. The Digital Archive combines historical records with local testimonies, while the Drop-A-Message game invites citizens to explore the aqueduct’s route. The Hadrian-net.gr platform, continues to connect residents to the aqueduct’s legacy. Smart water meters and the e-drohoos app promote sustainable water use by empowering citizens to monitor their non-potable consumption.

Similarly, Serpa is working to reactivate its historic aqueduct and the Nora well, seeing the restoration as a chance to reconnect residents with their water heritage. “We have an excellent opportunity to learn from different European partners and also share our experience,” explains Francisco Godinho, Serpa’s city Councillor “ the project is in line with the city strategic plans, we aim to implement innovative solutions that respect our historical legacy while returning these unique monuments to the community” he adds.

From a napkin sketch to a flowing legacy

Across these diverse ambitions, each transfer city intends to leverage the URBACT network’s structured framework of peer learning, transnational exchanges, and expert guidance to co-develop practical solutions. Through their URBACT Local Groups, the cities plan to anchor this learning locally, engaging stakeholders from across sectors to translate ideas into actionable steps.

[ The Deep-Dive visit in Halandri, January 2025. Photo: Sandra Rainero ]

Back in that bustling café in Halandri, when Giorgos, Nassy, and Kostas first asked, “So, what shall we do about it?” they couldn’t have imagined just how far their idea would travel.

If they were to gather again now, they might reflect with pride on the journey — how an ancient aqueduct sparked a movement that reached from the Elche’s palm groves to the underground river in Roeselare, from the revitalised Nora well in Serpa to the reimagined community spaces of Rome, and to Sombor’s plans to reshape its urban future around its industrial Great Bačka canal.

They might see how partnerships — between cities, citizens, and experts — have turned a simple question into a shared European answer: “We make it visible. And we give it new life.”

Article by Sandra Rainero, Hydro-Heritage Cities' URBACT Lead Expert.