According to the World Bank, over half of the global GDP is dependent on nature directly. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), one-third of climate mitigation needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement can be provided by nature-based solutions (NbS), while the World Economic Forum states (BiodiverCities by 2030) that NbS, in general, are 50% cheaper in urban infrastructure than grey infrastructure, yet they received just 0.3% of overall spending on urban infrastructure in 2021.

So, what are we waiting for? We need to raise awareness of all actors on the effectiveness of NbS and lead by example. Especially in Europe, the old continent, where 81% of EU protected habitats and 63% of EU protected species are in “poor” or “bad” conservation status (2020 ‘State of Nature in the EU’ report). As the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 says: “Europe’s protected habitats and species continue to decline at an alarming rate because the multiple pressures they face are simply too great to enable their recovery”. In line with the global goals, the strategy aims to “stop and reverse this trend by promoting the systematic integration of healthy ecosystems, green infrastructure, and NbS into all forms of urban planning”. The strategy also emphasises that 1€ invested into habitat restoration generates 8–38€ profit in Europe.

The use of NbS is also crucial to reducing disaster risks. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2022 Global Risks Report, “more than 1.4 billion people living in the world’s largest urban centres are at high or extreme risk of environmental disaster. Flooding has been identified as the most common natural risk across more than 1,600 cities, each with over 300,000 inhabitants. Accounting for all potential disruptions to economic activities, 44% of GDP in cities is currently estimated to be at risk from biodiversity and nature loss.” Another study, developed by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, showed that over 4% of deaths in cities during the summer months are due to urban heat island effects, almost half of which could be prevented through urban greening (Lungman et al., Cooling cities through urban green infrastructure: a health impact assessment of European cities).

It has been shown that due to its numerous co-benefits, urban greening has a benefit-cost ratio an order of magnitude higher than that of grey infrastructure. A factsheet created by the Network Nature clearly underlines that “demonstrating the economic viability of NbS interventions is therefore crucial to increase their uptake in urban areas, as well as to ensure public acceptance, which is key to the deployment of long-term NbS strategies. Both scientific literature and practice have been contributing to this evidence with cases where NbS represent the most economically viable approach, showing their economic opportunity”.

Let’s see some concrete examples from the BiodiverCity network as well as some of the case studies highlighted by the above-mentioned Network Nature factsheet, proving not only that NbS interventions are economically viable, but also efficient, cheap, aesthetic, and good for nature.

Natural Water Retention Measures

Natural water retention measures (NWRM) are multi-functional small-scale measures that aim to protect and manage water resources and address water-related challenges by restoring or maintaining ecosystems as well as natural features and characteristics of water bodies using natural means (e.g. log-dams, swales, hedgerows, buffer strips, ground dams, infiltration ponds) and processes, so that water can better infiltrate and be stored.

A key example we always refer to at the Hungarian Hub for Nature-based Solutions is the case of Püspökszilágy, a small village in Hungary, which has successfully minimised the costly damage earlier caused by regular flash floods in urban infrastructure. Püspökszilágy did it by using very simple and cheap natural water retention measures, namely seven log dams and a water retention pond in the catchment area. The settlement, which has also become an URBACT Good Practice, is currently working together with other municipalities on a decentralised NWRM network in the catchment area as a cost-effective option to protect urban areas from flash floods and increase the resilience of the landscape to droughts.

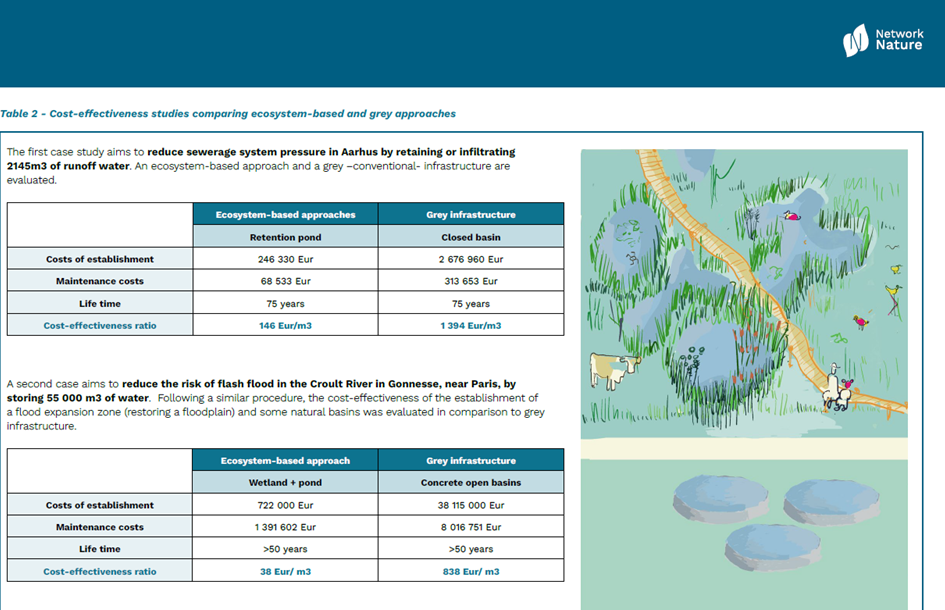

The above-mentioned Network Nature factsheet also highlights two great stories in this field, originally described in the report “Cost-effectiveness of NbS in the Urban Environment” (Panduro et al. 2021), produced in the context of the REGREEN project. In the first case study, the aim was to reduce sewerage system pressure in Aarhus by retaining or infiltrating 2145 m3 of runoff water. An ecosystem-based approach and a grey, conventional infrastructure were evaluated. In the second case, the aim was to reduce the risk of flash floods in the Croult River in Gonnesse, near Paris, by storing 55,000 m3 of water. Following a similar procedure, the cost-effectiveness of the establishment of a flood expansion zone (restoring a floodplain) and some natural basins was evaluated in comparison to grey infrastructure.

The difference is surprisingly significant: “in both cases, the costs of establishment, the maintenance and the cost-effectiveness ratios evaluated were significantly lower (from 21 to 10 times!) in ecosystem-based approaches than in conventional infrastructure. NbS are context-specific, and although one solution is the preferred option in one setting, it might not be the same in another scenario. This is clearly the case in the first table, where the retention pond is better suited for the city’s needs and much more cost-effective than grey infrastructure. It follows that nature-based interventions may be costly, but when considered in comparison with other infrastructures with the same function that are publicly financed, ecosystem-based approaches can be, by far, the most financially viable option”.

Climate-adaptive grassland management

Hundreds of cities across Europe have been experimenting with climate-adaptive grassland management in urban environments, which can provide multiple co-benefits (much higher biodiversity in dense urban fabric by providing food for pollinators, increased ecosystem services in comparison with an urban lawn, such as cooling, humidity, absorbing air pollution, and improving the water cycle). The Hungarian BiodiverCity partner city, Veszprém, has a flagship project in this field, which has also been awarded as a URBACT Good Practice, and which has been explained in a comprehensive BiodiverCity case study. By shifting from a conventional to a more sustainable management of urban lawns, Veszprém reported approximately 20% reduction of the appropriate costs (however, reducing costs is not the main driver behind the practice).

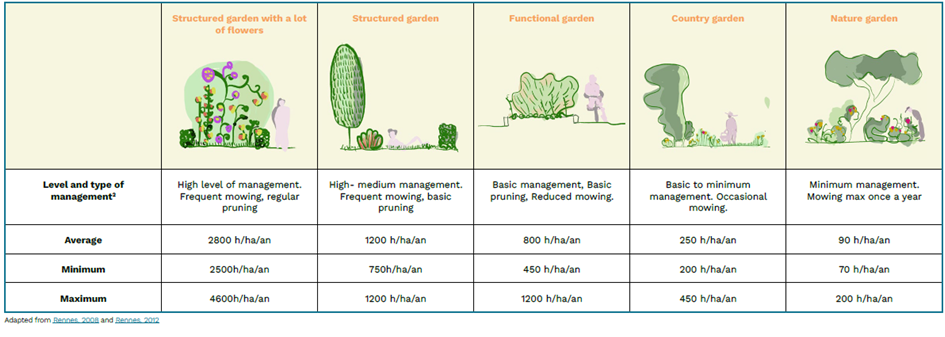

The Network Nature factsheet also deals with ecological park maintenance since labour represents 80-99% of maintenance costs of green spaces (Rennes, 2012), and thus it provides a relevant economic opportunity for implementing NbS and promoting biodiversity in urban areas. The table below, copied from the factsheet, describes the management needs of different types of green areas. “It outlines the economic advantages of switching from a conventional management (here called structured or functional), generally linked to low biodiversity and ecosystem services, to a nature-based management (country or nature), with higher ecological integrity and delivering a more extended range of ecosystem services.”

Table 1 - Labour time for urban parks management

Have ecosystem services in the long run instead of placebo trees in the short one

It is well known that urban trees provide countless and far the most ecosystem services within the city among the entire greenery to city dwellers, worth millions of euros, and mature trees with their big canopies are our most useful allies in climate adaptation. Despite all the benefits they provide, we treat our urban trees very badly: they can utilise less precipitation and live in a much drier microclimate than their forest counterparts, and in return, they have to take root in heavily compacted, air-poor soil and cope with a lot of pollution. No wonder our old trees are also being affected by unprecedented heat waves.

Obviously, using new methods to manage urban trees more sustainably, making them more resilient, such as using Stockholm pits or root cells, costs more. But, as Miguel Ángel Piñera Salmerón, officer of the Municipality of Cieza, said: “our aim is not to gain all battles, but the war”. He refers to the situation that unsustainable management of urban greenery also costs a lot in the short run, therefore it is financially worth to invest in changing the maintenance model. The BiodiverCity partner Cieza is a national frontrunner regarding the sustainable management of urban trees. Suffering from more and more serious heatwaves and drought periods, the Municipality of Cieza has understood that urban trees provide inevitable services and cost-efficient solutions for urban dwellers in the long run, and it has built up its comprehensive climate action in recent years, entitled Cieza Biofílica, which aims to transform urban green infrastructure into a complex green corridor as the backbone of the city. Over the last few years, Cieza also became a member of Tree Cities of the World, a network initiated by FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) and the Arbour Day Foundation, providing further impetus for Cieza.

Cieza has completely changed the model of how urban trees and greenery are managed, and it is well described in a new management plan. Among many other principles, for example, they have changed the pruning method, allowing trees to grow big canopies, they plant the right tree in the right place in as natural setting as possible and by using Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS), they intend to increase of tree cover with a maximum target of 30%, they promote species diversity while planting (30:20:10 - no more than 10% of one tree species, no more than 20% of one genus, and no more than 30% of one family in the city), and in general, they pay attention to the importance of planning, planting, quality, tree surround design and root control among others. In short, minimising nuisance and maximising benefits. This is, again, more costly in the short run, but if green infrastructure enjoys equal rights with other infrastructure, that’s cost-effective in the long run.

Demonstrating the success of the URBACT method in Poljčane (SI)

Transnational dialogue provided by the BiodiverCity network created a clear added-value not only for the Slovenian town Poljčane, but also on the national level – reported mayoress of Poljčane, Petra Vrhovnik. And this story is also about cost-effectiveness of nature-based solutions. In Poljčane, a core challenge is to prevent regular land (bank) erosion along the still freely meandering Dravinja river, which area is protected by Natura 2000 and national regulations. Locals have already tried many solutions, for example, initiated the use of willow and woven fences, but due to the strict protection of the natural landscape, they have not received permission from national authorities so far.

Thanks for the very active transnational dialogue between ULGs, colleagues from the BiodiverCity network confirmed that although the Natura 2000 directive links up local legislation, and the measurement of the potential impacts on the habitats and protected species of a planned intervention is rather country specific, using traditional, natural techniques such as the willow or woven fence on the riverbank or the riverbed should be in line with Natura 2000 principles and actually these technique were used in many protected areas (there was even a guidebook recommended on how to use willow and woven structures, published by the Polish Forestry Service). These natural solutions would not disturb the nesting area of Alcedo atthis, which was often among the reasons why the relevant governmental bodies denied permissions. Mr Miklós Toldy, an active ULG member from Veszprém, who is by the way a water engineer by profession, also explained during the study visit that based on public hydrological data, 50 % of the water volume in the river comes from the hill- and mountainsides, and thus flooding after the rain comes very rapidly due to the shape and the slope angle of the catchment area. NWRMs can be effective tools to retain as much water on the hillside as possible. It was also discussed that the new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in general allows compensating farmers if they provide ecosystem services, thus, giving up some low-lying agricultural area next to the river to let the flood spread out and to protect others or use them to produce willow and aspen brush for erosion control, can be an option too, but the use of CAP is also country specific.

After long discussions to convince decision-makers to start using alternative - and cheap – NbS interventions, the Ministry of Environment has finally applied the above mentioned technique as a pilot (in the Slovenian language, but photos from page 13 are very illustrative) to decrease invasive alien species on the riverbank, and the Municipality of Poljčane is now proposed to implement similar structures on several meanders in its territory.

Conclusions and co-benefits

Nature-based solutions can be used in various fields (according to a study made in Hungary, even continuous tree cover forestry as NbS can be economically competitive in comparison with “traditional” forestry methods (e.g. using clear cuts), but the use of NbS is always very much place-based. But in all cases, “a strong added value of NbS is the multiple co-benefits they provide in addition to the main societal challenge they are designed and implemented for”, however, the co-benefits associated with NbS are often difficult to monetise. “This calls for a need to rethink the way benefits, economic effectiveness and impacts are assessed for cities’ interventions to also account for such impacts when making decisions”.