"Rethinking for reorganising how we move" is one of the four themes RiConnect develops. In this theme, the network is aiming to integrate all mobility modes and favour a more sustainable and equitable mobility.

The main objective of mobility infrastructure is to physically support mobility flow types to ensure adequate accessibility throughout the metropolis. Rethink our existing infrastructure and reorganise the way we move is the RiConnect network’s first major step, rather than planning new infrastructure. How will this be done? We will optimise the use of combined means of transport in favour of more efficient mobility.

For many decades, urban development of cities was based on making the territory accessible using cars. This caused significant externalities including urban sprawl, territorial fragmentation, excessive public space occupancy, resource waste, pollution, accidents, and other issues. Accessibility based only on private mobility also ended up isolating some inhabitants due to their age, health, social status, gender, religion, location, or other factors; namely, people who did not have access to cars. RiConnect network is promoting mobility systems based on using means of transport that will assure accessibility for everyone, thereby reducing negative externalities. Achieving this will help us attain a more equitable metropolis.

TOWARDS EFFICIENT MOBILITY

New mobility’s demands on metropolitan areas, caused by the increase of inhabitants and number of daily journeys, should essentially be covered using active mobility and public transport. There are many advantages over private cars. Less space is occupied, thereby dramatically increasing the capacity of existing infrastructure. Externalities are reduced, making protective elements for spaces likely no longer necessary. Transport is more reliable, reducing traffic congestion costs if specific infrastructure is available, and it is more equitable, as there is no longer segregation due to economic, social, health, age or other factors. Relative to cars, however, this mobility should be competitive in terms of time, cost and comfort. Three main strategies have been seen in the first phase of the project:

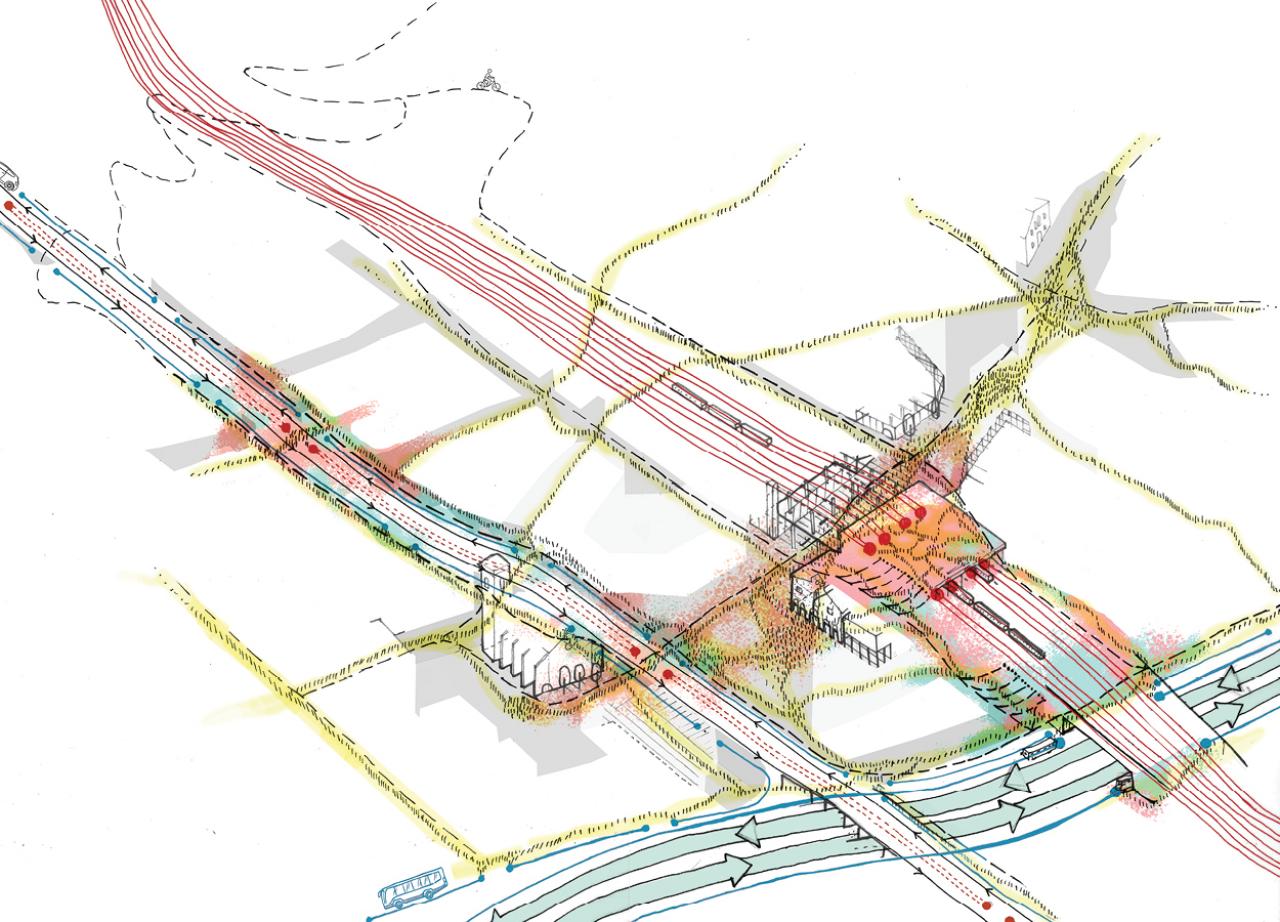

- Through the infrastructure: Reprogramming infrastructure mobility flows in order to incorporate and prioritise active mobility and public transport throughout its length at the expense of car space. For example, in Porto, a four-lane motorway will be re-shifed to introduce pedestrian walkways on both sides, as well as a bus and bike lane. Manchester is working towards similar goals.

- Across the infrastructure: Rethinking infrastructure can make it possible to introduce new mobility flows across infrastructure and reconnect both sides. This is Thessaloniki’s case, where various neighbourhoods can be integrated, ’only’ rethinking road and military infrastructure, making it possible for the city’s inhabitants to have more meeting spaces.

- Inter-modality and city hubs: In order to reach any final destinations (Last Mile) anywhere more efficiently, all sustainable means of transport must be integrated to facilitate transfer from one means of transport to another. They should be integrated physically, in the sense that they should be as close to each other as possible and have integrated management (including same fares, signage, coordinated schedules, etc.). Krakow and Amsterdam have experience in working on such inter-modality hubs.

TOWARDS EQUITABLE MOBILITY

Mobility infrastructure is related to citizen accessibility to all services and opportunities offered by the metropolis, including basic subsistence, accessibility to housing, workplace, education centres and services. This is not merely a functional matter. This is a fundamental right for all citizens. The importance of the role of infrastructure is undeniable as a physical support for all means of transport in guaranteeing adequate accessibility to all places. This is not currently happening, despite infrastructure’s overuse. Therefore, this network explores which factors lead to urban segregation in terms of age, health, disability, social status, gender, religion and location. It will then set up strategies and actions to tackle these.

The following are some points already identified by the European Institute for Gender Equality:

- Gaps in access to transport infrastructure and services

- Segregation within the transport labour market

- Weak representation of women in the transport sector decision-making process

- Gender-based violence in transport, which mostly affects women

CASE STUDIES

Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Development, Berlin, 2005

Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Development contains a range of criteria and guidelines for decision-making in gender-sensitive planning at various levels.

Key elements for knowledge sharing are short travel distances in a “compact and safe city” ensuring equal opportunities for people. Equal mobility opportunities are attained by optimising foot and bicycle traffic and providing convenient access to surrounding areas and the public transportation network and designing a safe network of paths for pedestrians and cyclists.

Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, Gdansk, 2018

The SUMP development process saw the implementation of a broad and detailed participation strategy, beginning with the working team itself. It was extended to city districts, stakeholders, inhabitants, interest groups, politicians and a wide range of experts from various professions. SUMP’s main objectives are: Improved conditions for active mobility, increased safety, improved accessibility, increased public transport, reduced transport externalities, increased quality and accessibility of public space and increased quality of life.

GOOD PRACTICES

- Cycle Hubs, Manchester

- Barcelona-Esplugues Bike Lane, Metropolitan Area of Barcelona

- Radbahn Bike path, Berlin

- Wetering Circuit, Amsterdam

- Railway Walk Along the E411, Belgium

- RijnWaalpad Bicycle Highway, Arnhem-Nijmegen, Netherland

- The Bicycle Bridges of Copenhagen, Denmark

- The Claude Bernard Overpass, Paris

- Cycle Roundabout Hovenring, Veeldhoven Meerhoven, Netherlands

- Luchtsingel, Rotterdam

- Express Axes, Paris

- Integrated Public Transport, Nantes, France

- Norreport Station, Copenhagen