Across European cities, data accumulates faster than people can absorb it, while shared narratives dissolve faster than communities can renew them. Yet behaviour, trust and belonging still change through story — through how people experience the city, themselves and one another. This article explores why stories function as urban infrastructure, how different groups inhabit different narratives, and why cities that understand meaning succeed where plans and datasets fall apart on their own.

The URBACT Pioneers Accelerator: A Timely Initiative

The URBACT Pioneers Accelerator programme arrives at a crucial moment, marked by low trust, changing public expectations and fragmented stories about cities. It brings together 27 cities from the Western Balkans and EU peers to learn, exchange and act for sustainable urban development.

In many of these cities - particularly across the Western Balkans - storytelling becomes essential precisely because trust in institutions is fragile, public narratives are contested, and participation carries historical and emotional weight.

As a storytelling strategist and mentor for Trebinje (BiH) and Nikšić (ME), two cities participating in the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator, I see the same pattern every day. When data alone no longer reaches people, stories step in. They create space for understanding. But when a community’s story becomes unclear or scattered, that same community begins to lose its voice.

The central lesson emerging from this work is simple: cities do not change by communicating better stories, but by creating the conditions for stories people recognise as their own.

For cities engaged in long-term transformation, this tension becomes especially visible as strategies multiply while shared narratives weaken.

Stories in cities

We have never known more, yet understood less. Never surrounded by more information, yet never felt more disoriented. In such a context, stories act as a compass. Not because they provide answers, but because they offer a frame through which information becomes meaningful.

Many European cities have undergone rapid modernisation - new public spaces, digital services and urban upgrades. On the surface, everything appears better than ever. Citizens, institutions, young people, businesses and local leaders rarely share a single narrative of change:

• Institutions speak the language of procedure and security.

• Citizens and young people speak the language of lived experience, identity and everyday meaning.

• Businesses speak the language of opportunity.

• Politicians speak the language of their voters’ perceptions.

These are not merely different discourses; they are different inner maps of the world. When we speak to people in one language while they think in another, misunderstanding grows - and misunderstanding leads to distrust, disengagement and, at times, even vandalism.

This is why the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator is built around mapping voices, conflicts and silences - from the Discover phase to real-life experiments through Action Labs with local stakeholders. The reflections that follow trace this same journey: from listening and collective sense-making, through testing change in practice, to imagining futures that communities can genuinely believe in.

What’s the next chapter for European cities?

Meaning is not something that can be promised. It must be confirmed in the lived reality of the community.

No narrative - however beautiful or complex - can activate a community unless it aligns with lived experience.

Stories that forget this remain elegant constructions, even fictions. Stories that understand it become the foundation of trust.

This is one of the core questions explored within the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator: how to translate analytical insight into a narrative that is credible enough to bring actors together, and practical enough to move them to action.

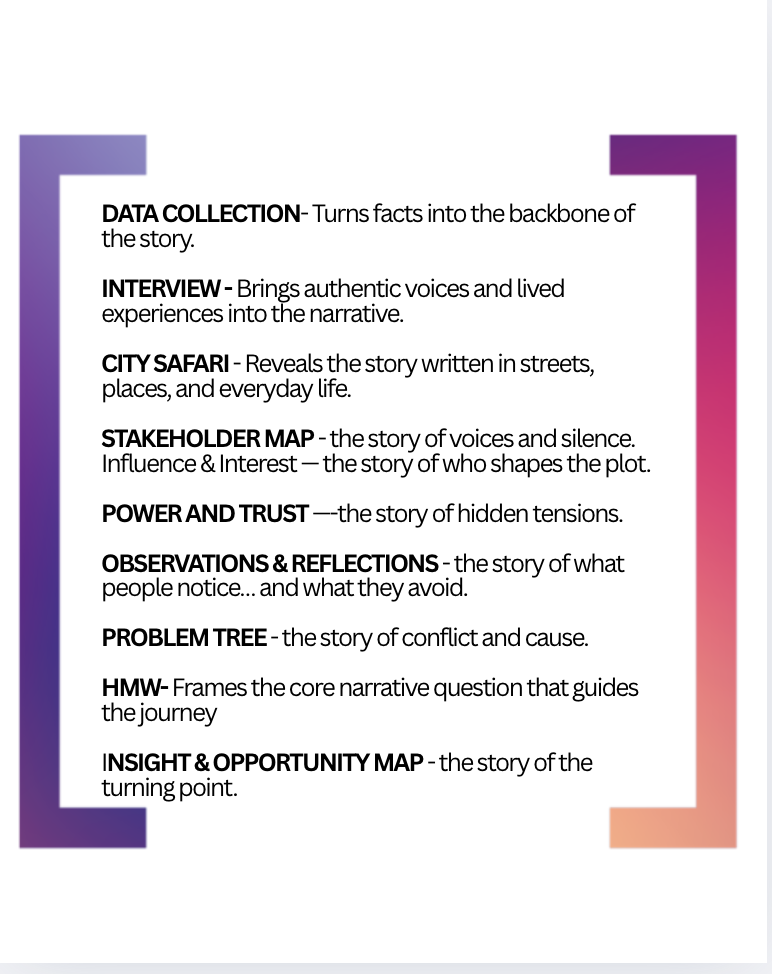

URBACT Pioneers Accelerator tools are therefore not technical instruments, but instruments of meaning-making.

We are not logical machines

Since the Enlightenment, humans have been perceived as rational beings. Then came Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist and Nobel laureate, who gently dismantled that illusion. He showed that most decisions are made by our fast, emotional and intuitive system long before the slow, rational system begins to calculate.

Kahneman — and later Ariely — showed that decisions are rarely the product of pure logic, but of predictable patterns of intuitive and emotional response. Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein translated these insights into practical wisdom: if you want to change behaviour, don’t start with explanations — start by changing the environment. In Nudge, they showed that behaviour is rarely shaped by arguments, but by the subtle signals in our surroundings that the fast, intuitive mind detects long before it processes any strategy.

The city is not neutral. It constantly nudges us — toward care or neglect, trust or fear, responsibility or indifference. This is precisely what Thaler and Sunstein describe as choice architecture in action:

In a dark alley, we feel uneasy. In a park full of children, we feel warmth. In a tidy space, we feel responsibility. In a neglected space, we feel permission to neglect.

None of these emotions are rational, yet all of them are real - because the environment itself tells a story. Humans do respond to facts, but beyond facts, we respond to the meaning we project onto them. This becomes immediately visible in the processes promoted through the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator. People do not withdraw because they “don’t care”, but because they perceive conflicting signals in their environment — or no longer believe that institutional narratives reflect their lived reality.

What behavioural theory describes in abstraction, URBACT cities experience in practice: participation rarely fails for lack of information, but for lack of shared meaning.

Changing the city’s default - Why environment shapes behaviour faster than beliefs

Thaler once said that the most powerful behavioural tool is the “default” - what is easiest to do.

If it is easiest to do the right thing, people will do the right thing. If the environment signals care, trust or order, people mirror that.

Change in habits rarely begins with motivation alone. As behavioural economics and social psychology have shown, it begins with context. Cities do not change through declarations or hope. They change when they change the environment in which decisions live.

This is precisely what URBACT Action Labs are designed for: to rehearse change in real conditions, test behavioural signals, and observe how people respond when the environment, not the message, is adjusted.

Yet context alone does not explain everything. Some groups can clearly distinguish between an authentic narrative and one that is merely well-packaged. They do not withdraw because they don’t care, but because they often find themselves alone in the gap between the institutional story and everyday reality.

When people refuse to participate, it may not signal a crisis of the people, but a crisis of coherence. Across the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator, this becomes visible session after session: people respond to signals from their environment, not to papers or plans. When teams change the context - the way space, tone and interactions speak and begin to walk the talk, behaviour starts to shift.

This dynamic becomes tangible in cities like Trebinje (Bosnia and Herzegovina), where everyday practices around public space revealed a deep gap between the official narrative and lived experience - a gap that only storytelling-based participation was able to surface.

When insight, not plans, moves people

Trebinje (Bosnia and Herzegovina) lives two parallel stories: a polished story and a lived one. As Petar Spaić, a student and URBACT intern with the local team, explains:

“Trebinje is one of the most beautiful small cities in the Western Balkans. With vineyards, stone houses, bridges, monasteries and preserved nature, it resembles a Mediterranean postcard. But there is another version of our city. A chronic problem of illegal dumpsites in the surrounding area. Over time, they have ceased to be merely a sanitary issue - they have become a narrative one. When a city lives two parallel stories, people stop believing both. Frustration grows, and withdrawal follows, because people are surrounded by two completely opposite signals.”

Nothing could change in Trebinje until these two stories met. When they finally did, storytelling itself became a key infrastructure of change.

Trebinje is not an isolated case. Whenever official narratives collide with lived experience, frustration and withdrawal emerge. At the same time, a different energy begins to surface — the desire to correct the story, to participate, and to test small but meaningful solutions.

Such moments are appearing across the region in cities participating in the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator, connecting them with EU peers. Cities that once knew little about one another now learn, travel, observe and recognise the same pattern: stories change only when people gather around shared meaning, not around documents.

Generational signals of a fractured narrative

We often overlook that young people are not passive observers. They are products of their world, but also creators of new meaning. Millennials, Gen Z and Gen Alpha are not younger versions of those who came before them. They are shaped by a different internal landscape.

Today’s younger generations are growing up in a flood of information that never stops, surrounded by stories that often end before they begin. Digital life has taught them something previous generations did not experience: stories no longer live in the monologue of institutions, but in the polyphony of countless voices.

They do not wait for stories - they rewrite them.

They do not accept narratives - they test them.

They do not want storytelling - they want authenticity.

Kahneman would say that under such pressure, the fast, intuitive system of the mind becomes continuously overloaded, while the slow, reflective system struggles to engage. Ariely would add that young people do not choose their “default” - they inherit it: a fast, algorithmic world of fragmented messages and environments that long ago stopped producing clear signals of meaning.

This default is not the same for all. For some, it appears as quiet withdrawal; for others, as frustration; for many, as confusion in a world that constantly offers something but rarely explains why it matters.

Young people are therefore more a barometer than a problem. They reveal where meaning has thinned, where narratives no longer hold, and where the environment moves faster than people can follow.

If there is one lesson here, it is this: change does not begin by convincing young people to return to structures that no longer speak to them. True transformation requires changing the signals - space, tone, rhythm and expectations — so that meaning can once again become a natural state.

Across the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator, these generational signals surface repeatedly during participatory sessions - particularly when cities attempt to engage young people through traditional consultation formats.

Local teams across the region have come to recognise “default” as a shared challenge: young people do not seek a perfect strategy, but a coherent narrative. They seek a place where they can shape the story, not merely listen to it.

This is why the programme’s participatory tools are so closely linked with meaningful storytelling.

Stories as urban technology

Stories are the first and last urban technology we have.

Their power lies not in words, but in the coherence they create among people sharing the same space.

European cities that treat story not as decoration, but as infrastructure, become places where people recognise themselves as part of a community. By embracing storytelling, cities can cultivate a sense of belonging and shared ownership.

Think of a city as complex hardware - its streets, squares and physical infrastructure. Urban plans, datasets and strategic documents are the lines of code. But without an operating system - a shared story and sense of meaning - the hardware cannot run. Participation and trust fail to function.

When the ‘OS’ - the institutional narrative - no longer matches lived experience on the ground, the system crashes. Citizens disengage. Trust erodes. People are caught between conflicting signals.

Within the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator, this understanding culminates in the Vision Pitch - a moment when strategies are no longer presented as plans, but as shared stories that can be felt, believed and carried forward by the community.

This is why the URBACT Pioneers Accelerator places storytelling at the connective core between analysis, participation and experimentation. Cities that understand their own stories find it easier to connect with communities that believe change is possible.

Sources and inspiration

The reflections in this article draw on insights from behavioural economics and social psychology, including the work of Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow), Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein (Nudge), Dan Ariely (Predictably Irrational), and David Shenk (Data Smog), alongside practical experience from URBACT Pioneers Accelerator cities.

By Mirko Mandic, URBACT Local Mentor