In many medium-sized and rural territories across Europe, commuting to work still depends almost entirely on private cars. This dependence generates high costs for individuals, congestion around workplaces, parking shortages, and a considerable environmental footprint. Every day, workers face a collective challenge individually: how to get to work in a practical and affordable way.

The question is obvious: in rural or low-density areas that lack the critical mass to sustain a frequent and efficient public transport service, and where hilly landscapes or long distances make active mobility unfeasible — what alternatives are there?

Starting from this question, and within the Beyond the Urban URBACT network, the county of Osona (Catalonia, Spain) launched a Small Scale Action (SSA) to explore carpooling as a potential solution. The aim was to test, at small scale, whether carpooling could become an attractive and realistic option to reduce car dependency, strengthen social cohesion and inspire new mobility policies for territories facing similar challenges.

How the SSA was organised and implemented

The SSA was designed as a collective learning experience rather than a simple experiment. Over one month, employees from three organisations with a Workplace Travel Plan were invited to take part by filling in a form with basic information — origin, working hours, vehicle availability — used to match compatible commuting groups.

The methodology followed four phases: internal communication and call for participation, selection of participants, testing phase, and final evaluation. Each step was carefully documented with both quantitative and qualitative data to understand not only what worked, but why.

The communication campaign emphasised cost savings, emission reduction and the social benefits of sharing a ride. During the test, participants coordinated through a WhatsApp group to organise daily commutes, share feedback and pictures.

One of the coples who shared the care

As incentives, they received free parking during the month and a gift pack of local products. At the end, two surveys — one for participants and one for non-participants — were conducted to identify motivations, barriers and organisational factors influencing behavioural change.

The SSA in numbers

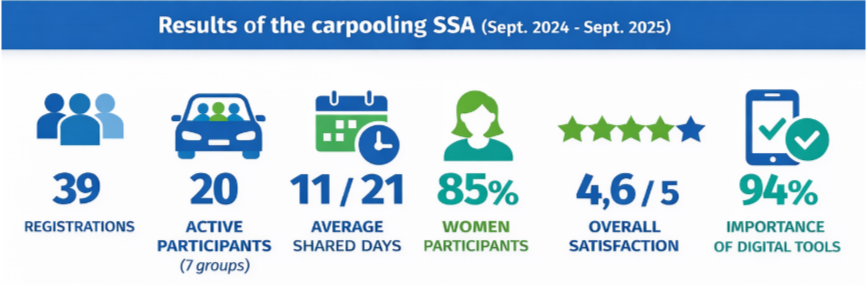

During the month-long test, 39 people signed up and 20 actively shared rides, forming seven carpooling groups. Most participants were women (85%), many working night shifts — underlining safety as a key motivation.

On average, groups were made up of 2.8 people per car and shared their commute on 11 of the 21 working days. Overall satisfaction was very high (4.6 out of 5), and almost everyone (94%) agreed that digital tools would be essential to expand carpooling in the future.

Gender and safety: carpooling as a tool for trust

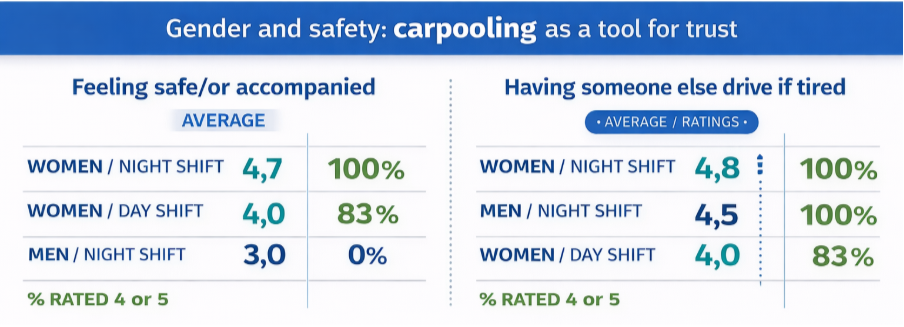

One of the most striking findings of the SSA is the strong gender dimension linked to safety and night commuting. The feeling of safety proved to be a key factor for women, especially those working night shifts.

When asked about the importance of feeling safe or accompanied until reaching the workplace, 100% of women commuting at night rated it 4 or 5 out of 5, compared with 83% among daytime women and none among men on night shifts.

Similarly, when asked about the value of having someone else drive when feeling tired, all women and men commuting at night rated this very highly (4.5–4.8), showing how trust and mutual support are integral to carpooling behaviour.

These insights suggest that carpooling can help address gender inequalities in mobility, offering not only a more sustainable but also a safer and more inclusive form of commuting — one that companies can actively promote and support through specific workplace policies. For women, especially those working night shifts or in isolated areas, sharing a ride is not just a practical solution — it is a way to travel with peace of mind.

What we learned

One of the clearest findings is that motivations for carpooling go far beyond saving money. Participants rated very highly the opportunity to socialise during the commute (4.8/5), feel safe and accompanied (4.3/5), and get to know colleagues better (4.6/5). Carpooling thus emerges not only as an environmental practice, but also as a social tool — helping integrate workers, build community and improve workplace cohesion.

The main barriers, however, are also clear. Scheduling compatibility is the biggest one: different shifts or variable working hours make matching more difficult. The lack of prior trust between people who do not know each other also limits participation, highlighting the need for spaces — both digital and face-to-face — to encourage initial contact. Finally, parking policies proved to be a decisive factor: most participants agreed that reserving preferential parking for carpooling groups would be a strong incentive.

Material incentives (gifts, raffles, etc.) help spark engagement, but the real key lies in structural conditions: adequate parking, aligned timetables and simple digital tools to manage the practice.

Recommendations for other territories

The experience offers valuable lessons that can easily be transferred to other medium-sized cities and rural regions across Europe:

- Trust and visibility. Carpooling grows when there is trust. Give visibility to existing commuting groups, share real stories, and create opportunities to connect — whether through an intranet, a bulletin board or informal meet-ups.

- Motivating communication. The three messages that resonate most are: economic savings, environmental impact and social value. Talking only about CO₂ reduction is not enough — people engage when carpooling is shown as something that makes life easier, safer and more enjoyable.

- Parking and structural incentives. Parking policy is a powerful lever. Prioritising spaces for carpooling groups, allowing multiple license plates per space, or offering discounts for long-distance commuters can be more effective than one-off rewards.

- Robust digital tools. To scale up, a shared platform is essential — one that matches compatible routes, automates cost-sharing and verifies participation. Gamification can complement, but not replace, these core functions.

- Recognise the social dimension. Beyond emissions, carpooling strengthens workplace cohesion and improves well-being. In places where commuting is a daily challenge, this social benefit can be as important as cost savings. Linking carpooling to workplace culture and well-being policies can multiply its impact.

Conclusion

Carpooling is more than a way to share rides: it is an opportunity to rethink everyday commuting and strengthen community ties. The experience from Osona shows that, under the right conditions, shared mobility can take root even in rural and low-density areas — turning a practical necessity into a driver of cultural and environmental change.