A particularly visible problem in Tartu Municipality has been the morning rush-hour traffic around schools. Every weekday morning at Kõrveküla School, the peaceful schoolyard used to transform into a traffic jam. Mass of car driving parents rushing to work pull over to drop off their children, make quick turns, or drive slowly past, while other students arrive into same congested zone by walking, by bike, or by bus. The result is a stressful start to the day for everyone: anxious parents, sleepy children, and numerous near misses.

This daily chaos inspired a group of parents to ask the municipality a simple question: could it be done differently? Together, we decided to test a straightforward idea as first step — to spread out drop-off points across the settlement so that not all cars would arrive in one place at the same time. From these points, children could walk the last stretch to school independently. This concept was implemented within our URBACT project Beyond the Urban as a small-scale action called “Jupike Jala” (“A Little Step on Foot”).

Logo Design

From the outset, we wanted students to be part of the project and to own it. To spark engagement, the school organized a logo competition with the enthusiastic support of the art teacher. Around 200 children submitted creative and clever designs. Ten of the best designs and the winning one was chosen by vote.

From the outset, we wanted students to be part of the project and to own it. To spark engagement, the school organized a logo competition with the enthusiastic support of the art teacher. Around 200 children submitted creative and clever designs. Ten of the best designs and the winning one was chosen by vote.

With the help of a professional designer, the winning sketch was refined into a logo for signs, posters, and T-shirts. The young designer remained involved throughout, seeing how their idea evolved into a professional symbol used across the community.

GIS Survey

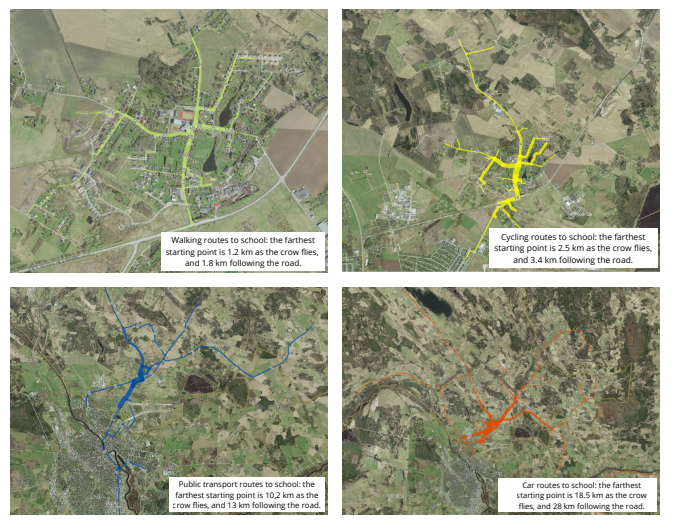

Every good story also needs solid data to support it. We carried out a travel journey survey among students and teachers. Older pupils mapped their journeys digitally on GIS maps, while younger ones drew theirs on paper. With remarkable participation — 464 students (67% of all) and 22 teachers (31%) — we gathered a detailed overview of mobility patterns.

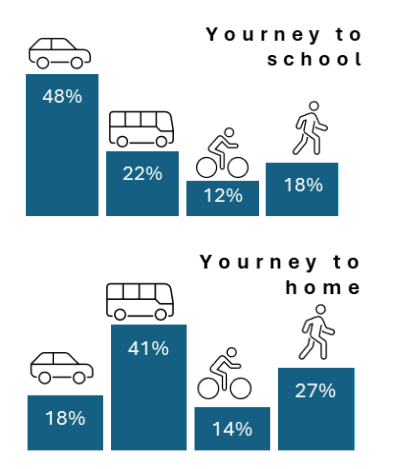

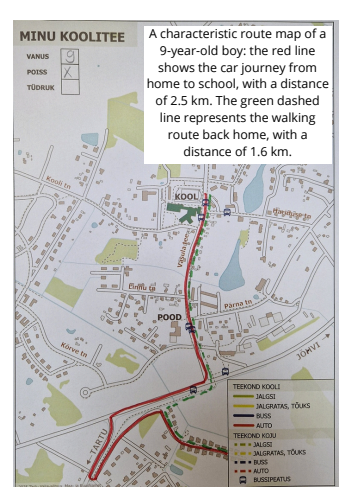

The findings were revealing. We knew that nearly one-third of students are living within one kilometre of school — a comfortable 15- minute walk — and 80% within three kilometres. Yet almost half (48%) still arrive by car. Only 18% walk, 12% cycle, and 22% use public transport. Interestingly, significantly more people used public transportation (41% of respondents) and walked (27%) when going home, indicating that many families drive their children to school simply for convenience, not because of a lack of alternatives.

This highlighted that parents’ daily routines strongly influence children’s travel habits: if a parent is commuting to work by car, it feels natural to drop the child off at school on the way.

The study also explored the reasons behind transportation choices. Among public transport users (59 respondents), the largest share rely on it as their only option (34%), while a significant number find it convenient (29%). Cyclists (34 respondents) chose this mode primarily for speed (50%) and convenience (21%), while walkers cited speed (56%) and convenience (16%). Both walking and cycling were also valued for health benefits. Car users prioritized convenience (30%), speed (22%), and alignment with parents’ commuting routes (22%). This shows that car travel is often chosen for convenience, either for the child or the parent.

Some notable comments from respondents illustrate the motivations behind their choice of transport. Car users explained their preference with statements such as: “The bus comes too early, and I can’t catch it,” “Because my parents want to drive me to school,” “It’s dangerous to cross the highway on foot,” and “So I don’t end up being late”.

Cyclists mentioned reasons like: “Because I can choose when to go home,” “Because I don’t feel like walking,” and “To stay healthy”.

Students who walk to school commented: “Because I live close to school,” “Because my dad doesn’t drive me,” “It feels nice to walk a bit during the day,” and “Because my mom doesn’t want to sit in traffic near the school in the morning”.

Finally, public transport users noted: “Because buses run here and I can use them,” “Because I have no other choice,” “Because my parents are in a hurry for work,” and “Otherwise, I’d have to walk”.

Students also marked dangerous and safe spots along their routes. Interestingly crosswalks were often seen as dangerous for children. They described it as "because cars do not stop“. But teachers saw crosswalks as safe, which revealed an interesting difference in perception.

Students also marked dangerous and safe spots along their routes. Interestingly crosswalks were often seen as dangerous for children. They described it as "because cars do not stop“. But teachers saw crosswalks as safe, which revealed an interesting difference in perception.

Students also complained about missing bike paths, bumpy roads, and poor visibility, which made them feel unsafe. Some children even pointed out a barking dog behind a fence that scares passers-by – a reminder that sometimes small details can affect a child’s sense of safety.

The data also provided many useful insights for planning infrastructure: where new pedestrian or cycling paths could be built, where are potential bus stop placements, areas with poor visibility, or potholes. Overall, the study offered excellent feedback on school routes, highlighting both safety concerns and opportunities for improving the local environment.

The study results showed that our initial assumptions about the main directions of school routes were largely correct. However, one additional route turned out to be more significant than we had initially expected. The next step was to identify safe stopping points along these routes, from which pedestrian and cycling paths lead directly to the school. Such locations were found in all access directions, and traffic sign–like “A Little Step on Foot” markers were installed there.

During the process, the pilot project grew larger than originally planned. Follow-up activities have already been scheduled: next spring, when the roads are dry, the routes from the “Jupike jala” stops to the school will be painted on the pavement, and movement games such as hopping on one foot, zigzag walking, and hopscotch will be added to make the journey more engaging.

The pilot project demonstrated that schools and students are valuable partners in shaping urban mobility. While the network of stops alone does not automatically reduce car use, limiting car access near schools can encourage walking and cycling, especially for students living within walking distance. Overall, the pilot was highly successful, and similar solutions are planned for other schools in Tartu municipality.

This article has been written by Tõnis Tõnissoo, the project coordinator at Tartu Municipality.