Local government actions to regulate housing markets and combat exclusion are showcased in a joint URBACT-UIA initiative.

Adequate housing is a right enshrined in international human rights law. But when property speculation and other factors inflate rental and real estate prices, what can cites do to ensure adequate and affordable homes for all? Measures to de-financialise housing were among the responses explored by urban researchers, campaigners and city representatives in the online ‘Fair finance’ conference, jointly run by URBACT and Urban Innovative Actions (UIA) in November 2020.

Any local efforts to provide fair access to housing are set in a complex context of international investment, fluctuating markets, and multiple levels of policy. With this in mind, the URBACT-UIA Fair finance webinar debated the roles, responsibilities and actions of local administrations in controlling their housing markets to fight exclusion, showcasing examples from partner cities.

What is the financialisation of housing?

“Housing is a RIGHT, not a commodity”, says the United Nations Special Rapporteur for adequate housing. The trouble is, housing has become a vehicle for global wealth and investment, rather than a ‘social good’. This shift is known as the financialisation of housing. The term covers a variety of strategies used worldwide to extract value from cities’ built stock.

One key factor is the buying up of low-price homes by private equity and investment firms who then raise rents, pricing the tenants out. “Almost overnight multinational private equity and asset management firms like Blackstone have become the biggest landlords in the world, purchasing thousands and thousands of units in North America, Europe, Asia and Latin America,” announced UN housing and human rights experts Leilani Farha and Surha Deva, back in March 2019. “They have changed the global housing landscape.”

While speculation creates large profits for investors, average citizens suffer from lack of adequate housing. In Europe, 80 million people faced overburdening housing costs just before Covid-19, and the number of people sleeping rough increased by 70% over the previous 10 years, reported FEANTSA, the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless.

The Covid-19 effect

During the coronavirus pandemic, house prices and rents have continued to rise in many areas, according to data presented at the recent European Conference on Housing Policy – despite measures such as temporary rents freeze or moratoria on evictions to protect the most vulnerable.

Manuel Aalbers, expert on financialisation of housing at Leuven University, foresaw in spring 2020: “when transactions and prices drop, private equity and hedge funds will be able to buy up large housing portfolios ‘on the cheap’.”

The long-term impact of Covid-19 is expected to intensify investment trends, reinforcing the gap between those who make profits from housing and those who need it for their life. As EU Urban Agenda Housing Partnership coordinator Michaela Kauer says,“…housing is at the heart of the coronavirus crisis; we need resilient housing systems more than ever”.

City experiments in regulating local housing markets

In the complex web of global, EU, national and local factors influencing housing finance, city governments have their responsibilities and roles to play. Public measures can have adverse effects, for example by supporting so-called ‘vulture’ investors, bailing out banks and (now) homeowners, or promoting the privatisation of public housing stocks without providing housing security for the most vulnerable. For these reasons, to ensure access to housing for all, government bodies at all levels have to work together to re-orient public policies against speculative mechanisms.

Although cities alone do not hold the power either to deconstruct or control financial markets, a set of legal and political measures – including the exercise of pre-emption rights, planning decisions towards commoning rather than privatisation, and eviction protection, as well as political and civil society pressures – can help revert the hyper-commodification of housing and the detrimental effects on inhabitants.

The URBACT-UIA Fair finance conference showcased two approaches to regulating local housing markets: in the city of Mataró, near Barcelona, with the UIA project ‘Yes we rent!’; and in Riga, partner in the URBACT Alt/Bau network.

Mataró: tenant cooperatives

In Mataró (ES), despite rocketing rents and sparse affordable housing, more than 3 000 flats still stand empty. So the city’s ‘Yes we rent!’ project encourages the creation of tenant cooperatives to re-use empty properties and increase rental supply. This municipality-led model provides benefits for homeowners to renovate flats (according to energy efficiency parameters), securing rental payment and tax exemptions.

In September 2020, the first owner signed to make his empty flat available to the 'Yes, we rent!' housing scheme.

The initial aim is to mobilise 220 units in order to constitute a stock of affordable flats for the city. Hence, owners will sign a contract with this new agent in the rental market, the housing cooperative, which will transfer the right to use (or ‘cession’) the apartment to one of its members according to its allocation rules. The hope is to change mindsets among residential property owners taking part in a project that goes beyond lucrative interest, and to encourage the solidarity of tenants through the city-wide cooperative.

Riga: taxing deteriorating buildings

The city of Riga (LV) has a shrinking population, thus speculative practices are less evident than in dynamically growing cities. The city introduced a regulation to increase property tax – by up to 10-15 times – on buildings that are classified as degraded, to encourage their rehabilitation. To do so, they established the Commission for the Inspection of Degraded Buildings. The threat of tax increases has led to substantial renovation activities. A similar measure could be applied to encourage the rehabilitation of empty residential properties to boost the provision of affordable housing in cities with tighter housing markets.

These examples are just two of the many wide-ranging actions and measures local administrations can adopt to control and de-financialise their housing markets. Vienna (AT), for example, has long-standing public social housing policies, with two instruments to regulate relations with institutional investors: 1) urban development contracts; and 2) a law, passed in November 2018, requiring that all new buildings larger than 5000 m² include at least two-thirds subsidised housing, for which rents may not exceed € 5 per m2, said Michaela Kauer during the URBACT-UIA web conference.

Meanwhile, Berlin has set up a rental freeze and exercises the rights of first refusal, and other instruments to prevent the exploitation of tenants. Citizens are also active, campaigning, for example, to expropriate Deutsche Wohnen, one of the largest investors in Berlin.

No city is immune

European Commission Joint Research Centre’s Sjoerdje van Heerden warned conference participants that European capital cities are not immune to the financialisation of their housing markets. Van Heerden, who co-authored the 2020 report ‘Who owns the city?’, said: “There is a need for researchers to further understand how the capital speculation unfolds in different territories, whether through touristification, golden visa programmes or investments by large corporate investors”.

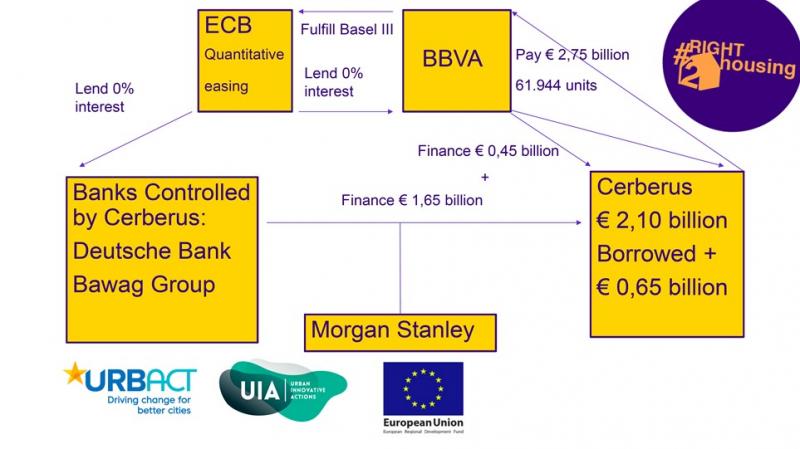

Manuel Gabarre de Sus, from the Spanish ‘Observatory Against Economical Crime’, pointed out that while the effects of financialisation become evident at the city level, the threads of speculative investments have to be searched beyond, touching European and global markets. A simple but powerful diagram shows that all levels of governments are implicated and bear responsibilities, including the EU banking system, lending to opportunistic funds such as Cerberus with a 0% interest rate.

The EU banking system contributes to the financialisation of local housing markets in the way it provides loans.

Recipe for curbing financialisation

International Union of Tenants representative Barbara Steenbergen set out a customisable recipe of instruments cities can adopt to regulate the private rental market and curb financialisation. First, she said, cities should start with the transparency of data, especially with local comparative rents to “know what your neighbour pays”. Second, when there are housing bubbles, adopt rental caps. Third, in the midst of massive speculation, rental freeze is fundamental. Fourth, cities should foster fair urban planning and putting a halt on sale of publicly owned stocks and land. And, finally, old and new legal measures should be deployed, while counting on the monetary support of the EU to build more affordable public social housing.

Pushing for adequate and affordable housing at EU level

Concluding the Fair finance conference, MEP Kim von Sparrentak, European Parliament rapporteur on affordable housing in the EU, presented her 2019 report ‘Access to decent and affordable housing for all’.

The report, linked to the work of the EU UA on housing, was adopted by the European Parliament Committee on Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL) with an overwhelming majority on 1 December 2020. Its proposals include increasing Europe’s affordable housing stock, having an integrated strategy on housing, fighting evictions and eradicating homelessness by 2030. The European Parliament plenary scheduled for 18 January 2021 will hopefully open up a new scenario for housing policies in Europe.

More to come

Though Fair finance is the final event in the series, URBACT and UIA’s joint work on the right to housing continues. Look out for upcoming podcasts, videos and more on the new online platform on housing in 2021.

More information:

URBACT-UIA Housing initiative, a one-year learning activity on “cities engaging in the right to housing” coordinated by Laura Colini, URBACT Programme Expert;

How to accomplish the ‘right to housing’ – examples from Berlin and Barcelona;

OHCR-UN Habitat factsheet ‘The Right to Adequate Housing’.