URBACT has been supporting European cities in the exchange and transfer of good practices. Most recently through the 2024 call, 116 practices were recognised for their sustainable development solutions.

Discover eight URBACT Good Practices that bring a new spin (and sometimes new tools and technologies) to nature-based urban regeneration – and ultimately, how your city can learn from them.

Urban biodiversity

Beyond its human residents, cities support a variety of living organisms and ecosystems. Preventing biodiversity loss, therefore, goes hand in hand with planning for climate neutral and resilient cities. The following cities have proven that nature-based solutions can be cost effective, require low maintenance and generate strong public buy-in.

#1 – Limerick (IE)

In Limerick, underused suburban green spaces have become laboratories for community-led sustainability. Through Sustainable community (sub)urban greenspaces, the city has worked with local residents to co-design and co-manage green areas in low-density neighbourhoods.

The initiative has empowered a network of Community Environment Champions to lead the charge, identifying local sites for improvement and delivering re-wilding, tree planting, pollinator gardens, and biodiversity zones.

#2 – Veszprém (HU)

The Wildflower cities project is promoting urban biodiversity and low-maintenance green areas by reintroducing native wildflowers into cityscapes.

This practice was originally intended as a cost-saving alternative to traditional mowing. It was initially met with scepticism and concern about the benefit of ‘messy’ or unkempt grassy areas in public areas. Nevertheless, the practice gained community support thanks to a smart public education campaign that reframes perceptions of ‘neglected’ grasslands as essential habitats.

The practice helps the city cut emissions and saved up to 20% of maintenance costs, all while promoting pollinators, saving costs, and raising ecological awareness. It also engages schools and citizens in seed collection and planting, turning passive spaces into active learning landscapes.

|

|

WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY FOR YOUR CITY?

A shared factor of both examples is the involvement of local residents in co-design and maintain green areas. The result? A replicable framework that enables the activation of bottom-up nature-based solutions in suburban and peri-urban settings.

Moreover, switching to wildflower meadows – as was the case in Veszprém – can be a low-cost, high-impact way of improving urban biodiversity and shifting public perceptions.

Seeing the forest beyond/for the trees

Many cities have green spaces with trees and wooded areas – but, until recently, their contribution to climate, health, and wellbeing remained unexplored. The following practices employ innovative forestry and ecosystem tools and services to protect urban forests, highlighting their essential role in creating healthier, more sustainable cities.

#3 – Perugia (IT)

The city’s Urban Forest Optimisation practice uses mapping tools and digital platforms to assess the services provided by its woodland areas (e.g. carbon sequestration, shading, air quality, recreation). This data supports better maintenance strategies and investment decisions.

Urban forestry plans have been developed by the city, actively involving citizens in the planting of a variety of trees as well as managing (with urban planners) the green and natural spaces.

Through workshops and local outreach, residents learn how forests support climate resilience and are invited to shape their future. The city also developed guidelines for other municipalities looking to follow suit.

#4 – Celje (SI)

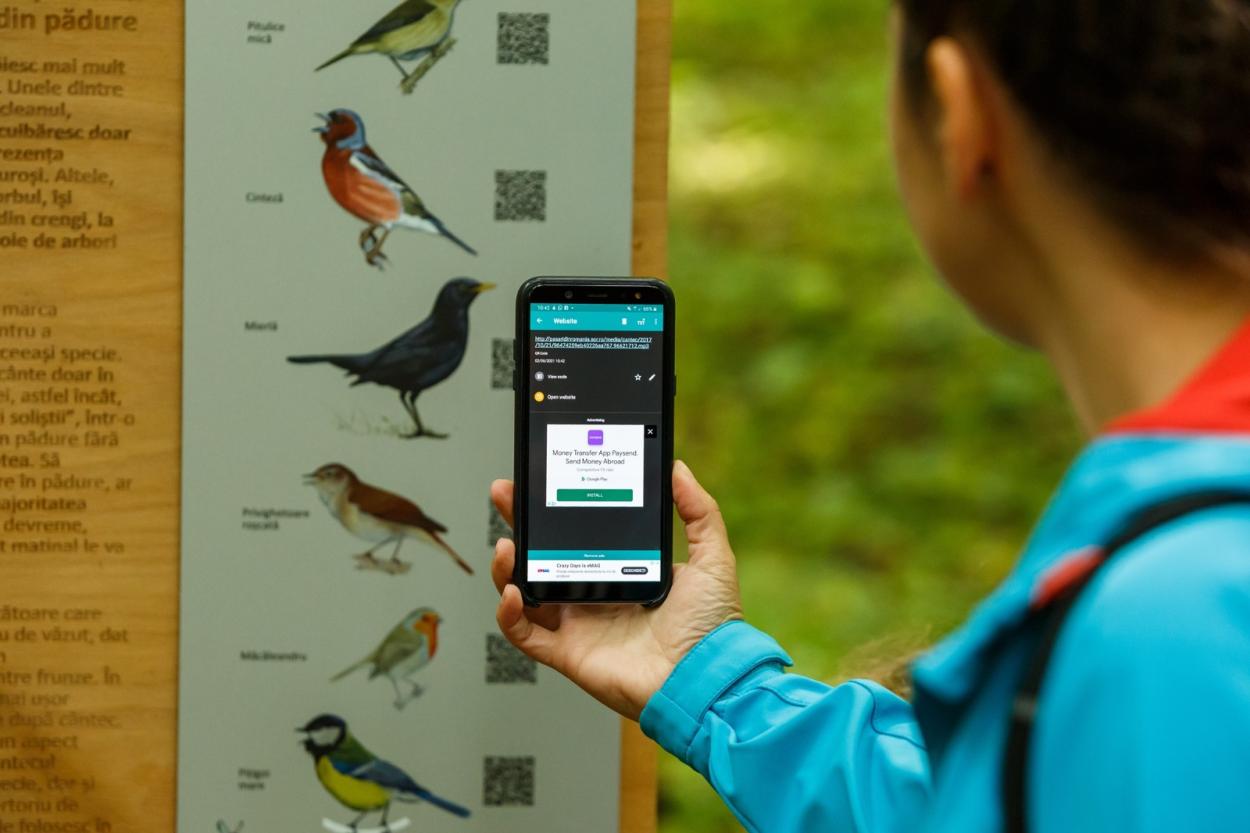

Through City Forest, Celje set out to transform its underused urban forest into a dynamic community resource. By upgrading paths, signage, and rest areas — and by involving schools and NGOs — the city repositioned the forest as a space for recreation, education, and wellbeing.

Most notably, the governance model is co-managed: citizens and municipal actors share responsibility for programming and care. It also demonstrates that forest assets close to city centres can become core elements of green infrastructure networks.

#5 – Cluj Metropolitan Area (RO)

The Mainstreaming ecosystem services and biodiversity project builds capacity among local and regional planners to integrate ecosystem services and biodiversity indicators into land-use policy.

Through training sessions, scenario workshops, and planning guidelines, the initiative helps embed ecological thinking into zoning and investment decisions. The metropolitan dimension is key: the practice involves multiple municipalities, aligning their development paths around shared environmental goals.

The region is also piloting green corridors, urban tree strategies, and participatory greening efforts.

|

|

|

WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY FOR YOUR CITY?

Reimagining urban forests as social spaces supports inclusive governance and stronger community-nature relationships. Looking at the above examples, cities that leverage digital tools, inclusive planning and educational initiatives, can unlock the full potential of their natural capital.

Guidelines, like the ones developed by Perugia and Cluj, can help other cities take on urban forestry and other effective nature-based solutions.

Natural infrastructure

Forests – like wetlands or dunes – are considered natural infrastructure because they are naturally occurring flood control, water filtration, or other preservation systems. The examples below show the need for knowledge and capacity building to ensure effective nature-based solutions that are consistent with local policies and governance.

#6 – Budapest (HU)

Through Biodiverse ComplexCity, the city has developed a multi-layered indicator system to assess the green potential of different urban zones. This tool – created in partnership with scientists, planners, and civil society – helps inform land-use decisions, guide urban planning, and shape greening investments across the city.

Budapest is embedding biodiversity into every stage of urban development. The approach connects ecosystem knowledge with spatial planning and makes the case for multifunctional green infrastructure that serves both people and nature.

#7 – Ormož (SI)

What happens when natural infrastructure becomes obsolete? In Ormož, the Transforming wastewater basins into a biodiversity hotspot initiative has transformed former wastewater treatment basins into a thriving nature park. Through ecological restoration and careful planning, the site now attracts over 200 species of birds and was listed among the finalists for the EU’s Natura 2000 protected areas network awards in 2020.

The practice also includes a nature education centre, observation towers, and walking trails — boosting environmental literacy and eco-tourism. Importantly, the project involved the local community throughout, creating jobs and enhancing civic pride. It’s a powerful case of turning industrial ruins into regenerative spaces.

#8 – Gátova (ES)

High in the mountains of Valencia, this city has embraced a comprehensive Sustainability Master Plan rooted in the natural landscape. Covering water, waste, energy, food, and mobility, the plan integrates nature-based principles and circular economy models across all sectors of local governance.

Despite its small size, Gátova shows how integrated planning and citizen involvement can turn environmental ambition into concrete action. The town is promoting regenerative agriculture, solar energy cooperatives, and sustainable tourism — all while preserving the region’s rich biodiversity.

|

WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY FOR YOUR CITY?

Evidently, repurposing post-industrial areas into biodiversity hubs brings environmental and economic regeneration (e.g. tourism, circular economy). As seen in Gátova, small towns can incorporate local ecosystems into long-term holistic sustainability plans for urban resilience.

Furthermore, using biodiversity indicators in urban planning enables data-driven greening strategies that work across departments. Digital mapping of ecosystem services helps cities optimise forest resources for climate resilience and public health.

Nature-based, city-focused

URBACT selected the above eight practices because they are effective and replicable: from suburban parks to regional forests, from post-industrial wetlands to mountain villages. They show that mainstreaming ecosystem thinking into urban planning can align nature, policy, and development goals. In this way, nature infrastructure can serve multiple urban goals: physical activity, mental health, climate adaptation, and environmental education.

Get inspired by browsing the full URBACT Good Practice database! Whether you are a large metropolitan area or a small town, you can tap into the URBACT Good Practice network to learn, adapt, and scale these ideas.

Interested in transferring inspiring URBACT Good Practices to your city? The call for URBACT Transfer Networks is running until 30 June 2025. There’s still time to apply!

Want to learn more about URBACT’s take on nature-based solutions? Nature-based solutions are a core area of expertise for the URBACT programme. Stay tunned and keep an eye on the Knowledge Hub as more content is coming by the end of 2025.

Want to keep on reading about biodiversity and Nature Based Solutions? Check out this URBACT study, which explains how understanding and planning for urban biodiversity and nature-based solutions is key to unlocking the full potential of these green spaces.