Perhaps public transport isn’t a viable option at night, so you need to save up for car-sharing. What if a stroller, disability or injury turns a simple trip across town into hours of planning to map out curb-cuts, ramps, and safe crossings?

While anyone can experience exclusion when urban environments fail to accommodate their needs, women, girls, gender-diverse people and other marginalised groups are disproportionately affected. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our mobility systems are not neutral, they reflect existing social inequalities. As cities work to overcome these barriers and become more inclusive and sustainable, ensuring gender equality in urban mobility is essential.

Gender-inclusive mobility was the main topic of discussion of an URBACT webinar on 5 March 2025. The webinar explored three key areas: accessibility, safety, and affordability. Through practical insights and real-life stories from diverse perspectives, the webinar encouraged participants to take steps toward more just and gender-aware urban mobility, while encouraging them to challenge their own biases.

Picking up where the webinar left off, this piece shares insights on gender-based exclusion in cities and some promising gender-inclusive solutions and resources.

Gender-inclusive mobility: a different approach to mobility planning challenges

Among the 291 participants in URBACT’s gender-inclusive mobility webinar, over 54% reported feeling excluded due to mobility barriers, primarily safety concerns, poor infrastructure, limited transport options and higher costs. An intersectional lens on mobility shows how overlapping socio-demographic factors, such as gender, age, race, and disability, shape exclusion. The more these factors intersect, the greater the challenges a person faces in navigating the city.

Building on the webinar’s insights, this article highlights a gender-inclusive approach that centres accessibility and inclusion in design. By adopting this broader view, city planners and authorities can go beyond single-identity solutions and develop mobility options that meet a variety of needs across different spaces. Inclusive mobility means planning cities for all genders, ages, abilities from the start.

Four solutions for gender-inclusive urban mobility

What do such solutions look like in practice? The following examples show how urban mobility can become safer, more accessible and equitable when professionals acknowledge and address their own biases and, most importantly, when they actively involve affected communities in the design process.

Mapping the city

Mapping is a powerful way to understand how people move through urban space and where they face barriers. Inclusive and participatory mapping initiatives can highlight unsafe areas, invisible routes, and gaps in infrastructure that traditional maps ignore. Using lived experience to gather data makes planning more responsive to real needs. Some examples of best practices include:

Safetipin is a social enterprise dedicated to enhancing public safety and inclusion, particularly for women in India with impact in other cities in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The app offers safety audits and detailed assessments of public spaces that are based on predefined parameters such as lighting, walk paths, and public transport. It also facilitates nighttime photographs to analyse lighting, pavements, and other features in the city. Collaboration with the Delhi government (India) enabled departments to make data driven decisions to make public spaces safer and more accessible for all.

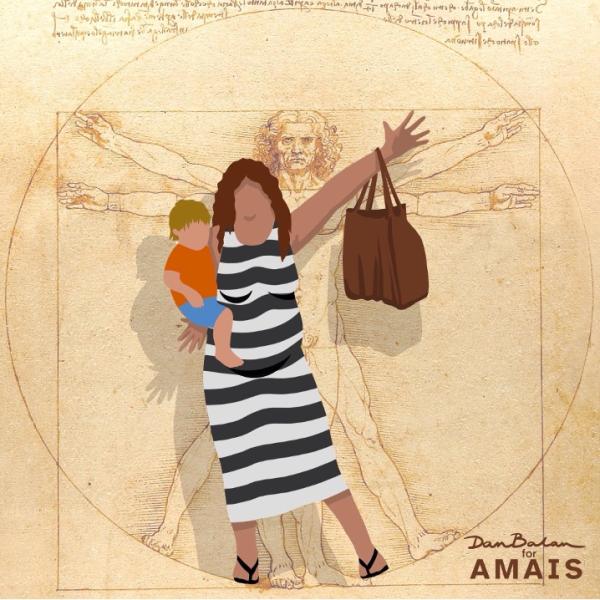

SeeYou app addresses the built environment's lack of accessibility. Developed by the Association of Alternative Methods of Social Integration (AMAIS) in Romania, the app facilitates connections between visually impaired users seeking assistance to reach specific locations and guides willing to help. Beneficiaries can select gender preferences and share live locations. Roll-out is planned in Bucharest and Cluj this year.

Infrastructure for safety

Safety concerns often affect people’s ability to move freely through a city. Addressing this means rethinking the basics: lighting, circulation, visibility/exposure, seating, and surveillance. Infrastructure designed with safety in mind not only prevents harm but also builds confidence, trust, and real freedom of movement.

Paris' RATP introduced on-demand alighting for all bus routes after 10 p.m. Passengers can request to be dropped off at a specific location, enhancing safety, especially in poorly lit areas. The initiative aims to support women and vulnerable individuals, offering more flexibility and security. It has expanded on a pilot programme and is now available on every bus route within the city after dark.

Umeå's "Station of Being" was developed through field research as a bus stop, catering to passengers' preferences such as standing or leaning while waiting in cold conditions. It features rotating pods made from locally sourced wood that adjusts to shield passengers from wind, offering comfort and privacy. It incorporates a "smart roof" equipped with lighting and audio cues to inform passengers of approaching buses, reducing the need for constant vigilance and allowing for a more relaxed waiting experience.

Street Harassment Prevention Act (SHPA), passed in 2018 in Washington, D.C., is the first U.S. law to define street harassment legally. Rather than focusing on punishment, the SHPA emphasises prevention through education. It created a community-led Advisory Committee, required public awareness campaigns, and in 2019, launched a transit ad campaign to show how street harassment affects people in diverse ways. Other campaigns can be found on the Women Mobilize Women Platform.

Access to public facilities

Creating inclusive mobility means redesigning public spaces to support diverse users through multifunctional street layouts, inclusive rest areas, and accessible facilities. For example, access to public restrooms is a key public amenity that significantly influences mobility choices, being for some a deciding factor in whether they can move through the city. This is especially true when caregiving responsibilities intersect with disability, making easy-to-navigate environments essential for ensuring independence and dignity in public spaces. Some initiatives that cover this topic include:

Trikala’s Cultural Center introduced a dedicated breastfeeding and baby-care space, which provides nursing mothers with a comfortable and private environment. This initiative supports inclusion and family-friendly facilities, allowing parents to fully participate in cultural events without stepping away for baby care needs. The project fosters community and encourages more equitable access to public and cultural life.

Changing Places is a group of organisations aiming to provide essential restroom spaces for people with complex disabilities who require additional equipment and space. Each facility includes a height-adjustable adult-sized changing bench, a ceiling hoist, extra space for carers, and a non-slip floor, ensuring dignity and comfort. It enables people with severe disabilities and their families to participate in public life without being forced to change in unsafe or undignified conditions.

Make Space for Girls is a platform that highlights how parks and recreational areas are often designed with boys in mind, neglecting the needs of teenage girls. Pushes for parks, playgrounds, and public spaces that encourage equal participation by considering how girls use and move through spaces. Conducts studies and collects data on how teenage girls engage with public spaces, ensuring design solutions meet their needs.

Tech solutions: open access and data fairness

Digital tools and smart technologies can help address gender gaps in mobility, but only if they’re built on inclusive data. From open-access platforms to gender-disaggregated mobility tracking, these tools must be designed to reflect diverse user experiences, not just reinforce dominant patterns. The following examples aren’t widespread practices in urban mobility settings, just yet. However, they highlight ways cities can begin rethinking their approach, serving as inspiration to develop strategies to train and use AI tools that avoid perpetuating biases in mobility and urban planning:

AI Fairness 260 is an open-source toolkit that help users detect and mitigate discrimination and bias in machine learning models. It is designed to translate algorithmic research from the lab into the actual practice of domains as wide-ranging as finance, human capital management, healthcare, and education.

Building without bias is an online dictionary designed to expose gender biases embedded within technology. It investigates how architectural language and design can perpetuate gender biases, particularly as automated technologies become more prevalent.

Keeping the momentum going: mobility that works for everyone

Inclusive mobility starts with a mindset shift and challenging our own biases: to reflect on how our experiences shape what or who do we see (and don’t see) in transport systems. Sometimes we take it for granted that women-identifying individuals, non-binary people and LGBTQI+ (including those with disabilities, toddlers, and other circumstances) should be considered and actively involved in the design of mobility plans.

Urban change requires collective effort. As is evident in the examples above, different groups, social enterprises and associations, and institutions can do their part. Talk to local municipalities, collaborate with NGOs, and bring diverse voices into planning processes. Empathy exercises like experiencing the city as and with a caregiver or a person with a temporary or permanent disability, can expose unseen barriers and fuel better design.

To dive deeper, watch the Gender-Inclusive Mobility in Cities webinar and access the PowerPoint presentation. You can also find links to solutions, tools, resources, and real-world examples.

Here are more resources for more information on how URBACT is working with cities to draw attention to – and boost – equitability:

For continued learning, consult the URBACT Knowledge Hub for expert insights on building gender-equal cities

Follow the activities of the FEMACT-Cities Action Planning Network