European cities are in a constant state of evolution, responding to a range of drivers and challenges in real time. City managers and urban development professionals are frequently confronted with the urgent need to identify and implement reliable, effective solutions. This is precisely why programmes like URBACT are so valuable: they identify successful urban practices, promote them, and actively support their transfer between cities across Europe.

However, city managers and urban development professionals need not navigate this process alone. We simply need to lift our gaze beyond the borders of our own cities and recognise the wealth of existing solutions available to us. The problem is that we often simply don't know about them – an ironic reality in this so-called “age of information”.

Over the past seven years, I have been actively involved in several such initiatives – leading two good practice transfer processes and testing various transfer approaches and tools. Lessons learned inspired this article, in which I share my experience of the transfer process within the context of URBACT’s call for Transfer Networks.

Transfer is not a Copy-Paste operation

Many times, we get mesmerised by good practice stories and solutions developed by other cities, leading us to believe that they are not relevant or implementable in our own cities. Too often, we conclude: “Nah, this can’t be done in our city!”.

However, arising urban issues such as urban sprawl, poor living conditions, the consequences of climate change, new technologies, etc., all serve as crucial motivators, compelling us to change and mobilise our citizens to act.

With 116 successful URBACT Good Practices already recognised, it becomes clear that we often know what to do, but not how to do it. I hear you wondering: “If another city already has a working solution, that is perfect. I can simply copy-paste it to my city, right!? Why should I take two years and even bother with a full transfer process?”

As usual, things are not that simple. An ideal transfer process involves close, constructive, and proactive collaboration between the successful urban practice owner and the transfer city, combining their efforts towards a common goal – successful transfer. Furthermore, any successful outcomes can be used to further enhance the original solution, creating a win-win situation that forms the foundation of a successful partnership.

Now that we know why, let’s dive-in and learn how to implement the three crucial transfer process steps. ![]()

Step 1: Understanding the good practice

As expected, this step is all about understanding the good practice, specific conditions under which it was developed, its structure, drivers, operating mechanisms, and all other questions a transfer city might ask.

Telling the good practice story and answering all posted questions usually proves harder than expected. Why? Simply because the good practice city developed it in line with its own needs, ambitions, resources, capacities, and most importantly its own vision of the solution. At the same time, the starting position of many transfer cities is in most cases not comparable.

We also need to take into account “the human factor”. The good practice is “their baby” and showcasing it might require some not so common working methods for a city administration – like in-depth city visits, good practice descriptions and presentations, revealing missteps and lessons learned, etc.

For example, during the Bee Path good practice transfer process, the City of Ljubljana organised a 4-day “boot-camp” for transfer cities and their key stakeholders. They gained full access having an immersive experience that all participants carried back home to their own cities, and that was key during the successful 2-year transfer process that followed.

Interestingly, the biggest challenge wasn’t the transfer itself, but describing the practice in writing. Its flexible, bottom-up design had never been formally documented. However, this gave us an opportunity to break the good practice down to its key components and describe it in a modular style. This approach effectively provided a menu for transfer cities, enabling them to select and transfer the parts of the good practice they needed the most.

In my experience, this is a very intensive phase for all transfer cities. At first, many cities were overwhelmed or sceptical. As Elena Giovannini from the City of Cesena (IT), one of our nine transfer city representatives said: “There is no way our citizens would accept urban beehives in the middle of a public park!” Yet, just 18 months later, there were not one but two urban beehives standing in Cesena. A clear testimony to a successful transfer process.

On the other hand, successful urban practice holders should not underestimate the complexity of the transfer process. While they possess all the knowledge and experience related to the urban practice itself, any attempt to transfer it is a tailor-made process that requires not only time, energy, and willpower, but also the development of concrete transfer tools, for example:

Good practice city visits and in-depth presentations;

Good practice descriptions, modularisation and transfer guidelines;

Precondition warnings, lessons learned, insights into both positive experiences and struggles;

Stakeholder involvement tools;

Training programmes, mentorship and support, etc.

All such tools must be developed, translated into mutually understood languages, and effectively used during city visits.

So, why are successful urban practice holders motivated to share? Many successful urban practice holders are proud to share their knowledge, solutions, and experiences. Furthermore, they recognise the opportunity to receive high-quality feedback from transfer cities, enabling further improvement and evolution.

For those interested to dig a bit deeper, in this article you can find several first-hand testimonies from cities just like yours on what it means to transfer an URBACT Good Practice.

Step 2: Adapting the good practice to your own needs

Now is the time to start thinking about your own city – your needs and ambitions, but also the availability of resources and your city-specific challenges.

The key word in any transfer process is "process". In our case this means proactive cooperation, learning, but also necessary adaptations. Subsequently, the good practice city must acknowledge that the original solution may not be directly transferable. Often, only parts of the original solution can, and nearly always, modifications will be needed to adapt it to the local specifics of the transfer city.

So, here are a few actions your peers have prepared for you, based on their personal experience from transfer processes. When adapting the good practice to your own needs, you should consider the following:

Check for any specific preconditions (legal, operational, etc.);

Identify key stakeholders, reach out to them, and understand their needs, capacities, and ambitions;

Ensure participatory planning and decision-making;

Align public-private interests and build public-private coalitions;

Ensure best possible data support for sound decision making;

Set minimum standards of proposed solutions to strive for;

Maintain process transparency.

Let me share a very concrete example. In the City of Bydgoszcz (PL) the use of bees in the city was prohibited, as bees were classified as farm animals. Subsequently, in the first step we had to address this crucial local-context precondition and change the local legislation. Just as importantly, none of nine Bee Path transfer cities had internal experts on the unique topic of urban beekeeping. This is why they all mobilised key stakeholders, established URBACT local groups and implemented the transfer process with them. The point being – there is no need to do it alone.

Above all, be smart and reach out for any available support. Identify and utilise opportunities provided by already mentioned EU mechanisms, programmes, or projects, which can offer a supportive environment, policy guidance, expert support, and funding for such processes.

Step 3: Reusing the good practice

If we truly want to achieve needed changes in our cities and address urban renewal, we need to reinvent our communities. Like it or not, communities are always built on trust. And the level of the trust within our communities determines if and how we can ensure the multi-purpose use of public and private space in our cities.

The same logic applies to almost all good practice transfer processes, as many of them are built on heavy stakeholder engagement and their success heavily relies on trust between the city administration and its citizens.

The following recommendations can be pointed out here:

Take from the good practice whatever you can.

Join forces with your key stakeholders, support cooperation and search for win-win situations – these will create ownership and build long-term local partnerships.

Develop a transfer concept, then test it and refine it on small-scale pilots, before aiming for full-scale implementation.

Once you confirmed the concept and tested it under local conditions, find local allies, resources and enthusiasm to implement it.

Then, let everybody know about your success and use the momentum to gain long-term local political support. Thus, ensuring that your solution becomes a new standard or service available to your citizens.

I hear you thinking again: “What kind of results can I expect from such approach?” In our case, the Bee Path good practice was, through two back-to-back transfer processes, transferred to nine cities across Europe – each one of them unique and adapted to local context, needs and ambitions of individual transfer cities.

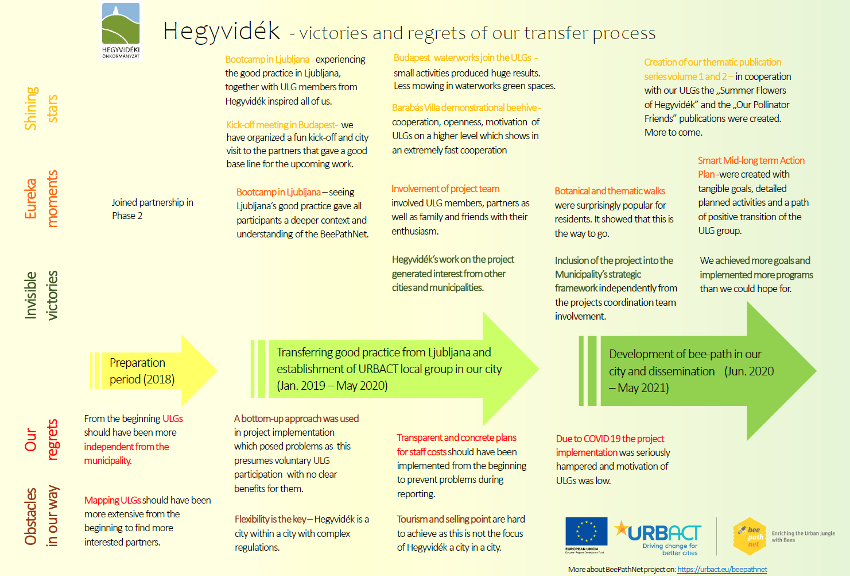

For example, Amarante (PT) and Bansko (BG) integrated their Bee Path into the educational system, Nea Propontida (EL) set-up a museum and developed several innovative tourism products, Osijek (HR) connected it to cultural and artisan heritage, Sosnowiec (PL) to its industrial heritage, Bergamo (IT) and Hegyvidék (HU) to biodiversity and awareness raising, and so on. Because we remained flexible in our understanding of what a transfer of the Bee Path good practice looks like, we ended-up with nine very diverse and tailor-made transfer results of the same good practice.

And Ljubljana? Well, Ljubljana evolved the Bee Path good practice with new educational and awareness raising points and turned it into an all-European level network of Bee Path Cities, with its own philosophy and vision of further cooperation.

I hope that provided lessons learned and presented results convinced you that it is worth investing time, energy and resources in transfer process. Especially, when you can benefit from support provided by programmes like URBACT. On that note – the call for Transfer Networks is open, so now, it is up to you to exploit this opportunity and go for it.

Look for other experiences

In my opinion, transfer processes are the most effective and efficient way of achieving desired changes in our cities. Furthermore, they usually result in very useful side-effects – like, built-up capacities, involved key stakeholders, empowered citizens for action, created ownership, strengthened communities, and improved the quality of life in your city.

I want to point out that above conclusions and recommendations rely solely on my own personal experience. This is why I urge you to look for other experiences and seek advice from other experts.

For example, the URBACT study written by Matthew Baqueriza Jackson has provided key insights into the experiences of the first generation of 23 URBACT city transfer networks. Another great reading material is the Good Practices Transfer publication titled Stories of transfer from Good Practice Transfer, why not in my city?

For conclusion, one last thought from my side: “Don’t think about it too much, because the time to start a good practice transfer will never be ideal… Start as slow and gentle as you need to, but do start!”