While it is now generally accepted that municipalities cannot design relevant and legitimate policy actions without a local partnership, many details of the modalities of stakeholder involvement are still unclear for public servants: how can they identify the right stakeholders needed for specific actions? How can they understand the motivations and capacities of these local partners? And how can they involve local actors in action planning and policy processes in the long term?

In URBACT networks, beneficiary cities are expected to create local multi-stakeholder groups, with people who are concerned and interested by the network’s topic and area of intervention. These URBACT Local Groups are constituted to accommodate a variety of voices in the planning process.

Leveraging on the URBACT tools

Given the paramount need to get all relevant actors around the table, the URBACT University that took place in Malmö (SE) from 28 to 30 August 2023, was conceived to explore the key dilemmas of the action-planning process. Designed for partners of the 30 recently approved Action Planning Networks through a series of workshops, the event offered tools and a learning trajectory allowing for more streamlined and inclusive work with local partners. Between identifying problems, establishing a vision, setting objectives and defining actions, one of the central elements of this learning trajectory was stakeholder mapping, which was the focus of the event’s second day.

As part of its Toolbox, URBACT offers a set of tools for stakeholder mapping and engagement. The Stakeholders Ecosystem Map is an intuitive tool that allows project coordinators on the ground to visualise the most important actors whose support and involvement is needed for specific actions. In order to have a better overview of these actors, they are often clustered, according to their profile, in public, private, civic or knowledge sectors.

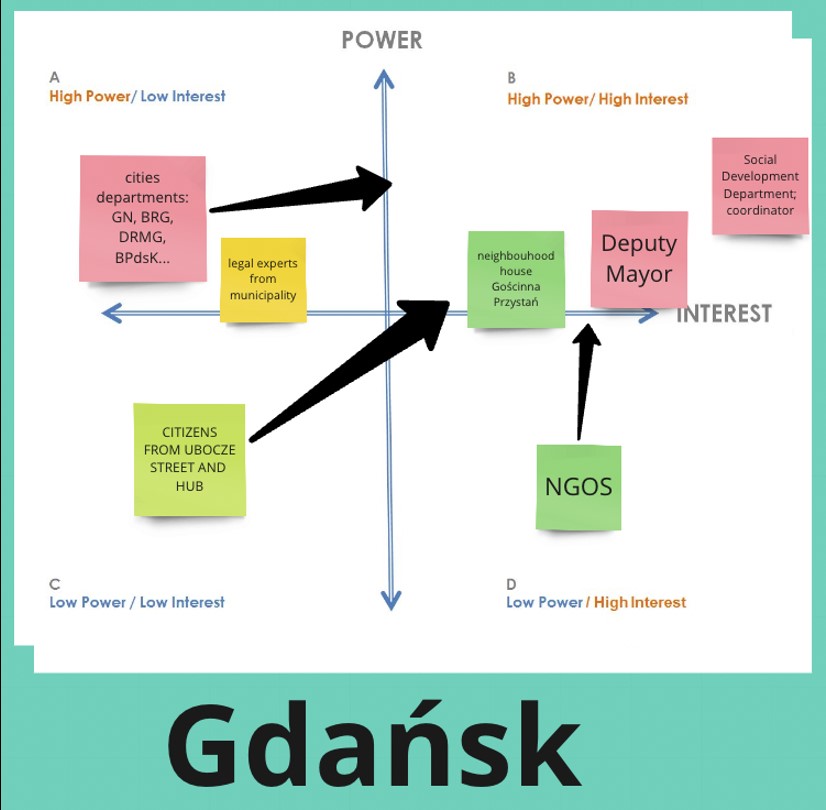

Another tool offered by the URBACT Toolbox is the Stakeholders Power/Interest Matrix, conceived to help understand the importance of different actors for a specific action from another angle. The Matrix consists of a coordinate system based on the perceived power and influence of certain stakeholders on the given process, on one hand, and on the interests of specific stakeholders to be involved in the process, on the other hand.

Both tools can be used in a workshop setting, where participants are invited to identify the most important stakeholders and place them on the Stakeholder Map canvas and then, following a logic process, rate the influence and interest of such stakeholder in the Matrix.

Who should sit around the table?

While it is important to remember that any individuals or groups who might have an interest in or an impact on a specific process can qualify as stakeholders, it’s also important that we recognise the most important ones among them. The Stakeholders Ecosystem Map tool allows for such classification by placing stakeholders closer to or farther from the stakeholder map’s centre, we can also indicate their centrality to the process, while also clustering specific actors.

The positions of actors in such a coordinate system have important consequences for stakeholder involvement strategies to start with, as well as for the organisation of stakeholder meetings. “We might need to conceive different forms of meetings for different partners”, suggests Liat Rogel, Lead Expert of the U.R.Impact, an URBACT network focusing on measuring the social impact of urban regeneration processes. “While core partners need to be informed about everything, this might overwhelm other partners”, adds Ileana Toscano, Lead Expert of the AR.C.H.E.THICS, a network addressing dissonant heritage. “They can, instead, participate in specific thematic working groups”, as Toscano goes on.

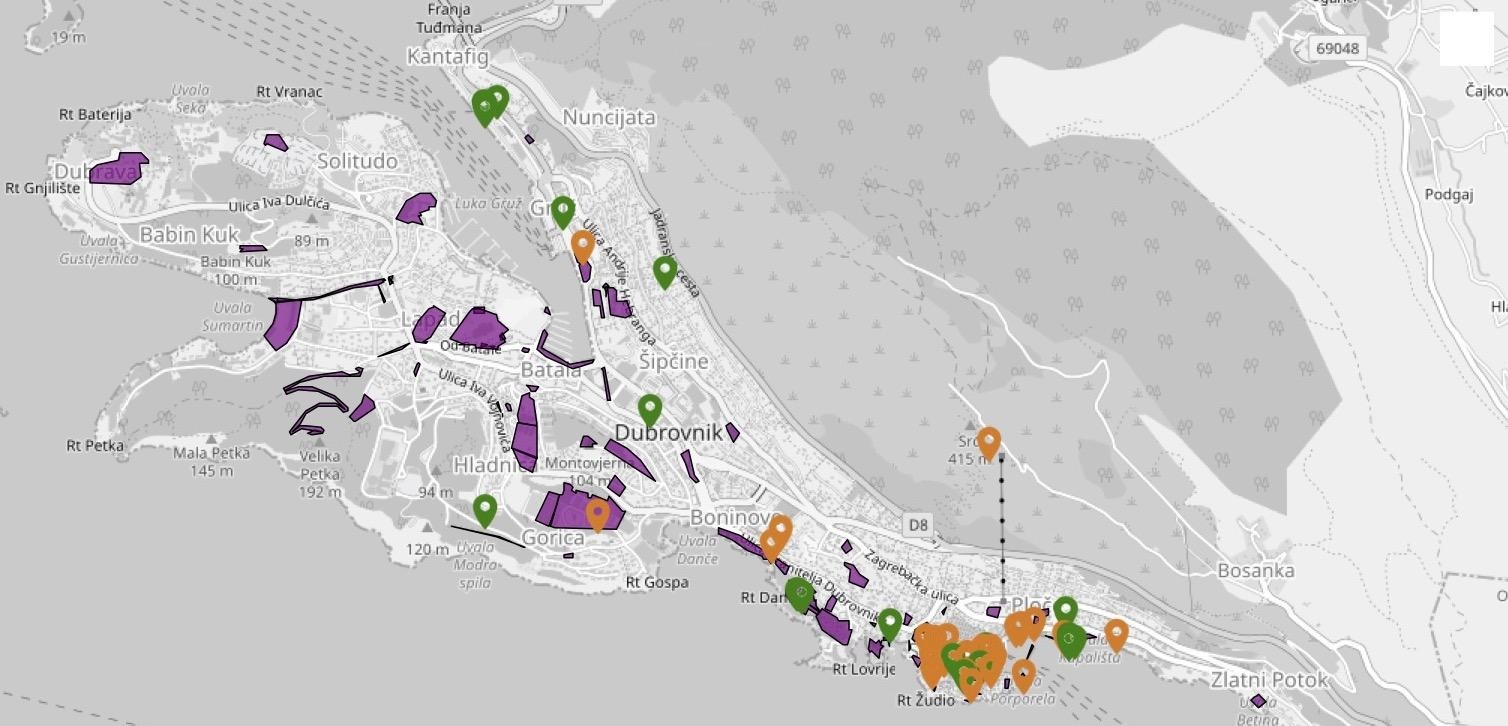

Due to its simplicity, the Stakeholders Ecosystem Map can be adopted for different purposes and be developed further to support the specific objectives of the network. For instance, from past experience, partners of the URBACT Transfer Network ACTive NGOs were inspired by the mapping methodology of the Madrid-based Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas (ES) and added a spatial element to their stakeholder maps. Dubrovnik’s stakeholder map (HR), for example, allowed public servants to have an overview of where civic initiatives operate in the city, the location of public assets, suggesting ways to develop synergies and collaborations between them.

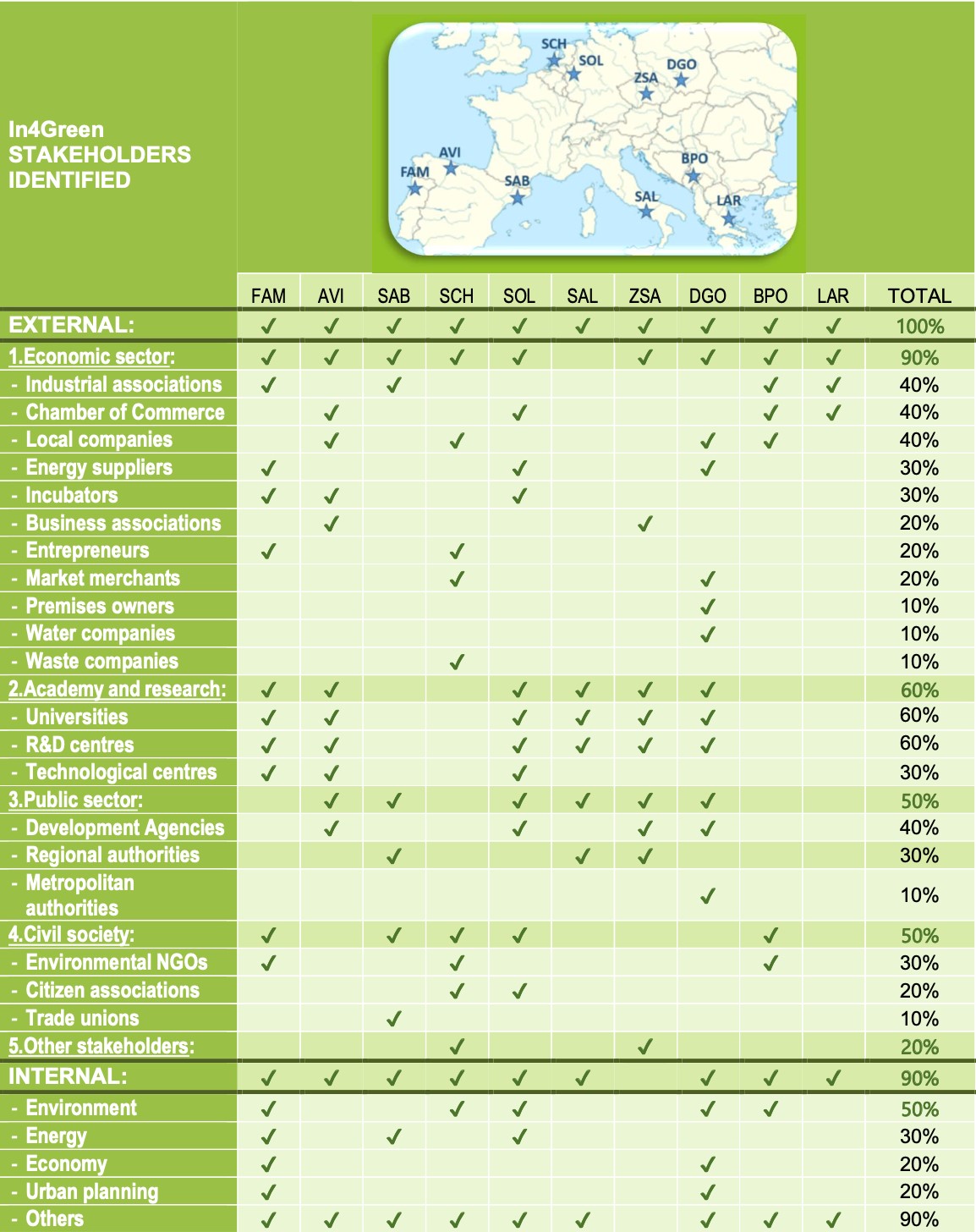

In the context of an URBACT network, it is useful to compare the local stakeholder groups from a city to another. José Fermin Costero Bolaños, Lead Expert of In4Green, a network undertaking the green transition of industrial areas, says “this process of comparing helped us to identify gaps in the local stakeholder groups, leading to suggestions of what other actors could be involved in each city”.

Such an external viewpoint and comparison is always helpful for municipal officers who do not necessarily have a complete overview of organisations and initiatives in their city. Other methods to extend local stakeholder groups can include tools like the “snowball” method, involving local actors themselves in identifying other key actors who might be invisible from the municipality’s point of view.

Who are your allies?

The Stakeholder Power/Interest Matrix tool helps municipal coordinators in better designing their communication, outreach and cooperation towards specific stakeholder groups. For example, actors with high influence but low interest need to be steered towards a more interested position – this group often consists of politicians or public agencies at various administrative levels. In turn, actors with high interest but low influence need to be empowered to gain weight in the process – this group often includes NGOs or formal and informal citizen groups.

Having a vision about how to proactively improve the attitudes of stakeholders towards a municipal innovation process contributes to a better planning of actions. In their Power/Interest Matrix for the URBACT Innovation Transfer pilot CO4Cities, public officers of the Gdańsk Municipality (PL) did not only indicate the current position of stakeholders according to their influence and stake, but also defined the desired future positions of these actors.

Besides their relationships with the action-planning process, stakeholders also need to be considered in their relationships with each other. Citizen groups might have an influence over politicians through their voting power, for example, while knowledge institutions can run campaigns to inform citizens about environmental challenges. “We need to anticipate the impact the planned actions can have on each of them,” suggests Raffaella Lioce, Lead Expert of the network Re-Gen, exploring ways to co-manage with youth groups abandoned or underused spaces for sports activities. “If specific actions distort the connections or power relations between different actors, it might also disrupt the whole ecosystem”.

Therefore, besides mapping stakeholders and classifying them according to their influence on the process envisioned by a partnership, it is also important to consider them as parts of a system of interconnections or an ecosystem. Such ecosystem-based thinking can help local partnerships understand better the interactions between actors and their role in local value chains, identifying resources that can be shared and exchanged. The recognition of such value flows between different actors enables local ecosystems to work towards a more circular logic of cooperation..

Undoubtedly, mapping stakeholders is just the first in a series of steps to engage them in the action planning process. There are many traps and obstacles in this process that might discourage partners from further involvement. Therefore, it is important to remain clear about the planned results and achievements, the possibilities and limitations of the municipality as well as the different responsibilities distributed among partners.

Co-creating actions

More than a single step in a process, stakeholder engagement is at the core of the entire action-planning cycle. While identifying and engaging stakeholders is the basis of setting up common objectives and planning joint actions, local partners can also have a key role in resourcing, implementing and measuring results. They need to be on board from an early stage, as understanding the roots of a local problem and co-designing visions. In order to assure the active involvement of all parts, it's essential to regularly re-assess the state of the URBACT Local Group, examining, and if needed, rethinking the stakeholder engagement strategies in place.

As the URBACT study on Integrated Action Plans reminds us, "URBACT Local Groups are at the core of the development of a good Integrated Action Plan", an important local output from the Action Planning Network's partners, so actions can be experimented and co-created. This was particularly the goal of the last day of the URBACT University.