As the impacts of the climate crisis become increasingly visible, and cities account for between 70-75% of total natural resources, and 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the need for change is urgent. The circular economy offers a way forward, one that reduces waste, keeps materials in circulation, and supports the regeneration of natural systems.

Recognising this, the 2025 EU Green Week (3 to 5 June) will focus on placing circularity at the heart of Europe’s economic transition. This priority reflects broader EU ambitions under the Circular Economy Action Plan — a core component of the European Green Deal — which seeks to reduce pressure on natural resources, extend the lifecycle of products, and promote sustainable economic growth. By shifting away from a linear “take-make-dispose” model, the circular economy supports climate goals, enhances competitiveness, and fosters innovation across sectors. In this context, URBACT is actively contributing to the transition by helping municipalities turn ambition into action, making cities more resilient, resource-efficient, and inclusive. Through peer learning and knowledge exchange, URBACT supports cities in designing, implementing, and transferring effective circular solutions.

This article presents four standout URBACT Good Practices, part of the 116 awarded in 2024 by URBACT, that are taking meaningful steps toward a circular future: C-City in Genoa (IT), Halle 2 in Munich (DE), Greening Logistics in Lucca (IT), and Viana Abraça in Viana do Castelo (PT).

Transforming supply chains for an urban circular future

#1 - Genoa (IT)

The C-City was developed as a strategy to transform key supply chains in the city by redesigning business models based on circular principles. Focusing on electrical and electronic equipment, textiles and furniture, some central elements of this approach are the Reuse District Centre, the Circular hub, and the Circular Desk.

Launched under the Action Plan Genoa 2050, the project has not only enhanced Genoa’s role in the field of innovation in the green and bioeconomy sectors but also improved the circularity of energy resources and influenced consumer choices towards circular products.

This initiative has fostered a more sustainable and resilient city, reducing the carbon footprint and non-recyclable waste, improving health and quality of life. It encouraged local stakeholders to adopt circular production approaches, attracting international funding and strengthening local services.

Key takeaways for cities:

Adapting the C-City practice to other cities requires an evaluation of local resources, demographics, infrastructure, and governance to identify circular opportunities. For example, it may involve assessing a city's waste management, energy use, transportation systems, and resource flows, in collaboration with governments, businesses, and communities.

Community event in Genoa, Italy, about the C-City practice. Credits: Genoa.

Reuse, repair, and rethink waste: a marketplace for change

#2 - Munich (DE)

The municipal second-hand shop in Munich, Halle 2, is a city-run second-hand store - both physical and online that combines sustainability with social impact. Located in a repurposed warehouse, it collaborates with local non-profit organisations, collecting items dropped off at recycling centres by citizens. By sorting, repairing and pricing them for resale, it gives them a new life.

The initiative is a vital part of the waste prevention activities of the Munich Waste Management Corporation (AWM). It helps extend the lifespan of all kinds of products, from bicycles to electronic devices. In addition, it also enhances the local labour market by creating new entry-level jobs.

Halle 2 has generated an income of EUR 60,000 per month on average, with around 200,000 items sold by year and around 4,300 customers every month, who spend on average EUR 13 per customer. This initiative has helped to upgrade 12 regular recycling centres in Munich, saving more than 500 tons of waste per year since its implementation in 2016, which means 2,800 tons of CO2 emissions per year.

Key takeaways for cities:

The Halle 2 practice is scalable and well-suited for further digitalisation as its key elements can be adapted to different city contexts by adjusting scope, infrastructure, and partnerships.

Core concepts such as reuse, repair, waste prevention, and community involvement can be implemented at smaller scales, with fewer partners and/or an online platform. In the same way, a physical store as a place for exchange can be any size or a pop-up. This approach should build on existing infrastructure, like waste collection points, and be supported by municipal public relations and awareness campaigns. Last but not least, strong cooperation with local NGOs, and ongoing political commitment are key factors.

Advertisement for the Halle 2 city-run second-hand store. Credits: Munich.

#3 - Lucca (IT)

Greening and innovating logistics in a historic centre is a practice that aimed to help the city achieve higher standards of energy efficiency and urban air quality, improving the residents’ quality of life.

To support sustainable freight distribution, the project developed and tested an innovative tool that uses a credit-based system to regulate and price last-mile deliveries more flexibly. This system is managed through the Logistic Credit Management Platform (Locmap), which is integrated with Lucca’s Restricted Traffic Zone (RTZ) access control system and is specifically designed for urban freight distribution.

In particular, three different technological solutions were put in place:

• 22 RTZ entry/exit gates with new Radio Frequency Identification system to monitor operators access/exit in/from the RTZ (operators were supplied with a specific tag with the entry permit);

• 34 Loading/Unloading parking lots, equipped with smart wireless sensors under the road surface;

• 3 cargo-bike stations with three cargo bikes available for transport operators.

The results were analysed by comparing conditions before and after implementation, demonstrating a decline in logistics flows and a consequent reduction of CO2 in the historic centre.

Key takeaways for cities:

A strategy for replicating and transferring the approach was developed and published, including partner cities’ experiences. The strategy addresses not only "what" to transfer, but also "how" other European cities and towns can implement the Aspire project’s approach.

In a nutshell, a successful replication requires a shared vision of what sustainable mobility and a greener city are among all stakeholders.

Example of a Cargo Bike Station in Lucca's RTZ (Restricted Traffic Zone). Credits: Lucca.

The power of compost: transforming waste into climate and social action

#4 – Viana do Castelo (PT)

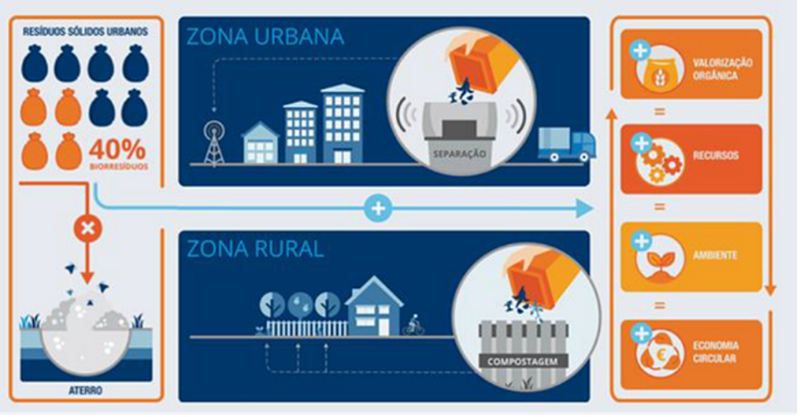

The Viana Abraça project is turning organic waste into a valuable resource instead of sending it to landfill. Through selective bio-waste collection and home composting, it achieves high efficiency - up to 72% or 96 kg per household annually - and channels savings to support local Social Solidarity Institutions of the Municipality.

The project provides clear benefits across the spectrum: it reduces landfill waste and greenhouse gas emissions by converting bio-waste into compost and energy; cuts waste management costs; reduces reliance on chemical fertilisers through circular reuse; engages citizens in sustainable practices and supports social institutions through the reinvestment of cost savings.

In rural areas, 8,122 domestic composters were delivered, treating 2,205 tons of biowaste at source. More than 14,000 families joined the biowaste separation project in urban areas. Given that before the project's launch in 2017, the municipality sent more than 12,000 tons of biowaste for disposal in landfills with an associated cost of EUR 276,000, euros; this practice is already making a difference.

Key takeaways for cities:

This approach is especially flexible, making it not only replicable in other cities, but also in other areas of the municipality. For example, in a historic city centre without selective food biowaste collection, a door-to-door system using smaller vehicles could be implemented.

When transferring this practice, adjustments should be made to meet the unique characteristics and needs of each city or area. Economic incentives and social benefits can be key drivers for public participation and long-term success.

Flyer promoting a waste separation initiative. Credits: Viana do Castelo.

The future of circular economy in cities

Collectively, the practices showcased here illustrate real change coming from local innovation and collaboration, in addition to replicable models that can be adapted and transferred to other cities.

These practices demonstrate that the circular economy is a creative, inclusive, and forward-thinking path, one that transforms waste into opportunity and communities into change-makers.

Explore more examples and draw inspiration from the 116 URBACT Good Practices covering diverse urban challenges such as climate action, energy efficiency, mobility, and social inclusion. Each selected practice underwent a rigorous evaluation by a group of experts assessing its local impact, participatory approach, integration, and potential for transfer to other European cities.

Is your city administration ready to join a network of EU cities adapting and adopting one of the latest 116 URBACT Good Practices? Find out about URBACT’s new call for Transfer Networks, running from 1 April to 30 June 2025. Join the online info sessions hosted by the URBACT Secretariat and ask your questions!