Part I: Sustainable Solutions for Social Housing

Offering more than a glimmer of hope, a sustainable city centre strategy can provide solutions to both of the city’s challenges identified in the Cities@Heart core framework: gentrification and adaptation to climate change. In this case, Granada is experiencing touristification, a phenomenon that resembles gentrification in that it results in population displacement, but in this case, the impact on local systems is caused by the influx of temporary residents—tourists. Making the case for an integrated development model central to all URBACT programmes, the city’s housing strategy creates new opportunities for lower income residents using existing materials and renovating historical buildings to ensure an improved demographic balance in the city centre.

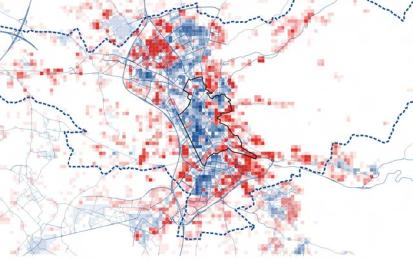

Population change in Granada between 1975 & 2020 Source: Cities@Heart Baseline Study

Offering more than a glimmer of hope, a sustainable city centre strategy can provide solutions to both of the city’s challenges identified in the Cities@Heart core framework: gentrification and adaptation to climate change. In this case, Granada is experiencing touristification, a phenomenon that resembles gentrification in that it results in population displacement, but in this case, the impact on local systems is caused by the influx of temporary residents—tourists. Making the case for an integrated development model central to all URBACT programmes, the city’s housing strategy creates new opportunities for lower income residents using existing materials and renovating historical buildings to ensure an improved demographic balance in the city centre.

Circular building lab Santa Adela in Granada Source: URBACT URGE Network

A member of circular economy networks during URBACT III and IV (URGE and Let’s Go Circular), the city of Granada has displayed a long-term commitment to sustainable construction strategies. Over the years, in the neighborhood of Santa Adela, the 1950’s housing stock became unsafe and no longer suitable for residents.The typical planning decision would have likely resulted in the demolition of the Santa Adela neighborhood, displacement of residents and construction of luxury apartments.

Choosing instead to preserve the spirit of the area as it once was, the city decided to rehouse all residents in a new living space primarily constructed from repurposed building materials. According to Juan Manuel Suárez Fernández from the Granada City council, the overall objectives of the redevelopment were to improve the living conditions of inhabitants while retaining population, thus contributing to socio-economic revitalization and social integration.

What is most unique about this development is the city’s commitment to combining a change in environment with a change in behavior. The social and educational programmes accompanying the housing project include a Habitat Pedagogy Programme, a Programme for Attention to Groups with Special Needs, a Temporary Rehousing Programme, a Community Organization Programme, a Socio-economic Development and Employment Programme and a Social Awareness Programme. In an effort to improve social mobility, the housing development also features education and socialisation opportunities centers where residents can develop a sense of connection to their new living space, learn new skills and access information about employment opportunities.

A derelict building in the Albayzín quarter Photo: Cities@Heart

The Santa Adela rehabilitation project provides an example of sustainable tactics to transform housing policy using mid century building stock as source material, which of course poses its own challenges. But what about buildings dating back centuries with unquantifiable heritage value and in a severe state of dereliction? This was the challenge in the Albayzín neighborhood, a World Heritage Site exemplifying Granada’s unique position as the last Muslim Kingdom of Spain at the dawn of the Renaissance.

One nearly forgotten building in the Albayzín hiding wonderful treasures. The building houses ancient Arab baths and is in the process of being excavated by Yedra Architects. Photo: Yedra Architects

In 2001, the city’s data painted a grim picture of the area with 23% of the population being over 65 years of age, 27% vacancy rate for homes in the area and 41% of the buildings in poor condition. The city’s Albayzín Special Plan aimed to restore the neighborhood with a people-focused approach, from a place full of decay to full of life, welcoming to families and complete with urban and social services.

Visiting the renovated Casa Cuna during the Cities@Heart transnational meeting

In this quarter full of heritage, ageing structures have been given a new life. Casa Cuna provides an emblematic example of a historic structure successfully renovated to provide social housing. The living standards of the former orphanage declined through time as it was transformed into messy and non-functional housing. Managed by ABBA Architects, the renovation project presented a number of challenges, namely preserving the original layout of the building all while adapting the project to modern needs and building codes. As with the Santa Adela project, in the galleries and courtyards, the architects focused on creating pleasant, welcoming shared spaces in an effort to instill a sense of ownership and community.

The Alhambra Palace. Photo: Cities@Heart

PART II: Adaptation to climate change

Elsewhere, in the Alhambra district, as downtown living in Granada becomes more costly, communities have found ways to adapt, not only to their changing city but also to an evolving climate. Taking their inspiration from a European directive and a national programme, Albayzín and Realejo residents decided to create the Comunidad Energética Barrios de la Alhambra, an energy community. The concept of an energy community is simple: a group of individuals come together to form a non-profit cooperative to produce, share and consume their own renewable energy.

Javier Pérez Sáez from the CEBA (Comunidad Energética Barrios de la Alhambra) and Elena del Moral from the OSCE (Oficina Social de Comunidades Energéticas). Photo: La Ampliadora

The cooperative functions thanks to successful partnerships with private and public actors. Investors finance the solar installations in exchange for a small amount of interest as a financial return. In a historic neighborhood like the Alhambra, when requesting authorisation to install solar panels, residents confronted challenges such as historic building codes. The community asked permission from the city council to install solar panels on the rooftops of public buildings in exchange for a small percentage of the energy produced, which will be distributed to vulnerable families. In the long run, the energy community will reap the benefits of achieving energy independence. In 2024, the cooperative counted 51 families and 5 small businesses with a project that gives back to the community, reserving a percentage of energy or energy-related income for neighborhood improvement initiatives and households in need.

An integral component of the Cities@Heart framework, inclusion is essential to the health of the city center. Providing affordable housing to citizens of all socioeconomic backgrounds ensures better diversity in the city center allowing locals to remain in their communities and preserve the social fabric of the city center. Whether a project involves restoration of heritage sites or completely rebuilding contemporary housing, a human-focused approach ensures the improvement of living conditions for locals and a preservation of local character. The energy-sharing community model also contributes to creating a more equitable city centre, varying supply modes, lowering costs for vital resources and instilling a sense of belonging between neighbors.

As explained by Angel Luis Benito, Technical Director - Urban Agenda, Sustainability and European Funds, the city has also launched environmental initiatives aimed at improving the urban environment and air quality. These include traffic restrictions through a low-emission zone covering almost the entire municipality, the Green Belt project to enhance vegetation coverage and CO2 absorption, and an urban re-wilding initiative that encourages residents to participate in tree-planting efforts in every district.

PART III: Over Tourism

Tourists in the city centre of Granada. Photo: La Ampliadora

With an accessible low-cost travel market, over tourism problems are growing worldwide and Spanish counter-movements are garnering media attention more and more. In nearby Málaga anti-tourism fervor has attracted an international audience. Residents protesting over tourism have created a sticker movement that parodies the apartamento turístico seal designating tourist apartments featured on websites such as AirBnB. The AT letters featured prominently on the sticker have been transformed into witty acronyms generating phrases in Spanish proclaiming “tourists go home!” or “a family used to live here”.

The conflictual relationship with tourism is not a problem unique to Granada or Spain. Across the globe residents and local stakeholders are calling for better regulation of quotas and rules for visiting popular sites. At the international level, the 2024 Glasgow Declaration on Climate Action in Tourism calls for an overhaul of the sector to integrate urgent climate adaptation objectives. In 2021, the Spanish Ministry of Industry and Tourism released a Call for the Extraordinary Plan for Tourism Sustainability in Destinations. Funded by the European Union and part of the country’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, approved projects are fully subsidised. Indeed, as the second tourist destination in Andalusia and the sixth in all of Spain, the city of Granada has recognized its problematic relationship with tourism and is working on creating a new offering capable of stemming the tide of visitors with a plan grounded along four strategic axes: green transition and sustainability, energy efficiency, digital transition and competitiveness.

The Alhambra palace against the backdrop of the Sierra Nevada mountains, viewed from the Albayzín quarter. Photo: Cities@Heart

Presented by Daniel Galán, Tourism Executive for the city, the main objectives of the new plan are to broaden the destination and expand ecotourism. An extensive bike path network and renaturation of an aqueduct encourage ecotourism while new digital content and an automated tourism kiosk provides information to tourists without placing excessive strain on public ressources. Additionally, to remain competitive across national and international markets, the city will be improving the energy efficiency of municipal buildings, seeking management assistance, renovating historic sites and implementing the SICTED Quality System for Tourism Destinations.

From an urban governance and planning perspective, the city has taken action by implementing unprecedented restrictions on short-term tourist rentals to mitigate their impact and prevent conflicts with local residents. Recently, designated "tourism density zones" have been established, where no new tourist accommodations can be introduced. Additionally, any new rental property must have a separate entrance from traditional residential units. As a result, the number of tourist apartments has decreased by 113, from 2,855 in August 2024 to 2,742 today.

Granada can serve as a cautionary tale: be careful what you wish for. Tourism brings economic growth but without proper management, the losses can outweigh the gains, resulting in the homogenisation of local businesses and forced exodus of local populations. Going forward, the city could benefit from enacting programmes to help small businesses and further regulate short term rental properties. Cities like Granada can look to key passages in the Glasgow declaration for inspiration in defining their future goals relating to sustainability and inclusion.

“Regenerate: Restore and protect ecosystems, supporting nature’s ability to draw down carbon, as well as safeguarding biodiversity, food security, and water supply. As much of tourism is based in regions most immediately vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, ensure the sector can support affected and at-risk communities in resilience building, adaptation and disaster response. Help visitors and host communities experience better balance with nature.”

In March 2024, the URBACT Cities@Heart network organised their second transnational meeting in Granada, Spain. The meeting aimed to focus on the issues of gentrification and adaptation to climate change.