For many civil servants working in municipalities around Europe, sustainable urban development is something of a “no-brainer”. Public transport, energy efficiency, green and open public spaces, citizen engagement, and social inclusion - these are topics that municipalities almost have in their DNA to deal with.

That said, approaching sustainable development can be controversial. In some parts of the world and in Europe, issues like green transition and sustainable development are increasingly becoming targets of political polarisation. For some, it is seen as something imposed from the top that disrupts their daily lives, rather than something that provides benefits and secures a future for all. For others, according to global research, actually the majority of people, the climate emergency and other sustainable development challenges call for more radical solutions and for governments to act with more sense of urgency.

For civil servants, who in their professional roles need to remain politically neutral and whose main task is to implement policy set by democratically elected leaders, this context can be difficult to navigate, especially when engaging with people who hold different political opinions and beliefs.

That is why we came together with a group of local civil servants from the Agents of Co-existence network to uncover how civil servants can engage citizens in sustainable development..

The Agents of Co-existence network aims to, inter alia, strengthen the skills and competences of civil servants to boost civic participation, whereas its sister network Cities for Sustainability Governance (for which the author was former Lead Expert) aims to support civil servants to strengthen implementation of sustainable development goals through a fresh look at their governance. In this intersection, we explored how municipal staff can go about those tasks (sustainability and citizen participation) without getting tangled up in political polarisation that seems to be on the rise regarding sustainable urban development topics.

“The world we want”: the 2030 Agenda and SDGs

Before we dig in, let’s take a step back and look at what we mean by sustainable development in this context.

In 2015, the world was ripe with hope as leaders from all 193 UN member states came together to endorse the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, providing the world with a roadmap to a sustainable future. The 17 goals encompass all dimensions of sustainable development and were designed based on broad-based consultations and negotiations among UN member states. They apply to all nations, albeit acknowledging the need to support developing nations onto sustainable paths of development.

The 2030 Agenda puts cities at the heart of global sustainable development through a dedicated goal for sustainable cities and communities: SDG11. It is the first time that sustainable urban development is so clearly recognised in a global agenda.

Beyond SDG 11, many cities further used the momentum created in 2015 to build their own local 2030 Agendas and translate the SDGs into their local realities. The backdrop of a globally agreed agenda provided a great framework and context for addressing long-term holistic sustainable development locally. Since the goals were already endorsed by all national governments, cities almost had the green light to directly start delivering results on the ground. The “SDG localisation” process typically includes four steps:

Raising awareness about the SDGs locally and starting a participatory process.

Setting a shared SDGs agenda together with local stakeholders.

Identify actions that can contribute to achieving the SDGs.

Monitoring and evaluating progress through local monitoring systems.

As we can see, citizens are at the centre of implementing the 2030 Agenda locally and are the first “target” of local authorities wishing to address the SDGs. Cities have gone about this in various ways, from creating pedagogical tools for schools, to setting up local ambassador schemes or “citizen alliances” that help municipalities localise the goals. One of the key advantages reported by cities using the SDGs framework is its holistic nature - the goals help to make sure no issue is overlooked.

In addition, the SDGs have been a framework used and endorsed by governments from across the political spectrum, hence providing a “neutral” tool for civil servants to use when raising awareness and engaging citizens in sustainable development, at least in most contexts and at its early phases. When national and local politics have differed, the global agenda has further provided a bridge of universally accepted long-term goals. For examples of cities tackling the SDGs, check out the URBACT knowledge hub or the Global Goals for Cities learning kit.

Is sustainable development becoming a controversial topic?

The promise of the 2030 Agenda was to promote sustainable development for everyone, everywhere. It was seen as a universal agenda that would guide all nations, regardless of political regime. And while both the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs were unanimously adopted by all UN member states, they have become targets of political polarisation. This is the case not the least in the US, where the current administration claims to have “set a clear and overdue course correction on ‘gender’ and climate ideology that pervade the SDGs”. In Spain, the Vox party discarded the SDGs in their 2023 campaign poster by figuratively throwing them in the bin (see image below).

Election campaign poster from the Spanish Vox Party 2023. Source: RTVE.es

This tension of course trickles down to the local level. In cities, we can see people engaged on both sides of the spectrum, from Fridays for the Future pushing for stronger political action on climate change, for example, and those protesting against initiatives like low emission zones or other climate actions.

In the online academy, we reflected on what may be some controversial topics related to the SDGs and sustainable urban development in the participants’ local contexts. SDG 13 on climate change and SDG 5 on gender equality were brought up, but also concrete issues like large numbers of mosquitos and how to tackle them - using natural or chemical solutions - were highlighted as controversial.

The key issue here is that local civil servants must navigate political divides while staying neutral and fulfilling their set role in democratic societies (that is, implementing policies decided by elected representatives). What’s more, they must carry out their role while working closely with citizens around topics that affect their everyday lives, whether it’s related to climate change, social equality, or how we govern our cities democratically. But how to do this while staying clear of political polarisation? How can civil servants work with long-term goals like the SDGs while remaining politically neutral?

Four strategies for civil servants to engage citizens in sustainable development

In “Sustainability in the Face of Political Polarization”, Riley Barlett and her co-authors highlight a few strategies that civil servants can apply to cope with the issue of political polarisation. Their ideas inspired the recommended strategies below, which were presented in the session.

Spread awareness based on science and data

Emphasize potential cost savings and other co-benefits

Use “neutral” or alternative language

Provide spaces for dialogue and deliberation

Scientific evidence is key to spreading awareness and so to speak “depoliticise” sustainable development issues. Raising awareness based on science has been widely used in the environmental and climate action space. For example, the Climate Fresk is a tool for providing quality climate education that is “neutral and objective and presents only established scientific facts” (quote from the organisation’s own website). Participants in Climate Fresk workshops learn about the root causes and consequences of global warming in a visual mapping exercise. They are presented with scientific explanations and get to discuss what may be done to mitigate and adapt to climate change and its consequences. While such educational efforts are key to engage citizens and depoliticise the issues, some caution has been raised on making climate change appear as a purely technocratic issue, since there will always be political power and social choices involved in developing solutions.

In the Cities for Sustainability Governance, Lead Partner city Espoo, Finland, is a frontrunner when it comes to SDG driven governance and strategy-making. One of the key tools applied by the city in this context is the so-called Voluntary Local Review (VLR) - in essence a review of SDG progress on the local level, using data points to report the current situation in Espoo for each of the 17 goals. Not only does this help to raise awareness about sustainability, but also provides a more objective view of progress and areas of improvement. What’s more, it sets the scene for the dynamic review and refinement of the city’s strategic goals.

Focusing on “other” benefits of sustainable development can be a powerful way to keep engagement among citizens, especially when talking about SDGs or green transition may be controversial or seem overly abstract. Examples include supporting energy savings for households, which not only helps a city cut carbon emissions, but also helps people save money. The València Energy Office is a good example: by explaining energy bills and promoting energy savings to its users, they foster a culture of energy transition as a co-benefit.

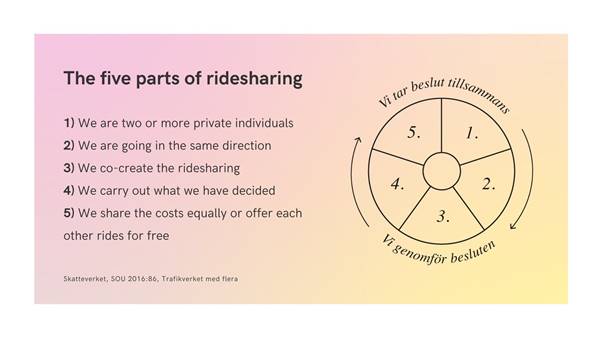

In the online academy, we also took a deep dive into the growing ridesharing movement in Sweden - led by the non-profit association Skjutsgruppen. Ridesharing is a good example of how people can enjoy social, economic and environmental benefits of something as practical as sharing a ride from point A to B. This civil society movement represents a key solution in Sweden’s overall climate actions, however, the main motivation for many of the people engaged in the movement is that it solves a very practical transportation problem. At the same time, it is good for social, environmental and economic reasons. A number of municipalities in Sweden have started to work with Skjutsgruppen to harness these benefits, both for their own staff and local communities. Through so-called “commuter evenings”, people come together to map travel routes and needs, then start ridesharing together. This is a great tool for citizen engagement; as the founder of the movement highlighted in the session: “it is very hard to rideshare alone!”.

In relation to the above, sometimes adapting the language used around sustainable urban development can help to engage a broader spectrum of people. For example, most cities that work with the SDGs agree that the goals often seem too abstract in the beginning; it is when working together with citizens to define the local agenda that things become more concrete and understandable. This is also an opportunity to find expressions that resonate with people locally, removing some of the jargon and tension around issues seen as political or “imposed by Brussels”. Talking to a civil servant from the Slovak city of Kosice, one of the European 100 Smart and Carbon-neutral Mission cities, he put it point blank: “In our context, we have stopped mentioning green transition or net zero altogether. Instead, we use the EU Mission label to visually signal concrete interventions and promote them as things that are ‘good for people’ in the city. We tell people that because we care for the elderly population, we need to preserve green, shady areas that could be used for private developments, for example”.

The Agents of Co-Existence Lead Partner, the city of Genk, has gone some way in creating local vocabulary and values that resonate widely among its residents while promoting an inclusive society, called “the Genker Habits”. The habits provide 4 groundrules that apply to all Genkenaren, established through a participatory process and reflecting key principles such as mutual respect, active listening, and the value of integration. To explore the Genker Habits, check out this article.

While the above strategies can help civil servants in their role as politically neutral agents, we may also accept that no sustainable urban development topic can or should be depoliticised. In this context, the role of civil servants can also be to provide spaces for deliberation and informed debate among citizens.

In this line, it is interesting to look at for example citizen assemblies, which provide a structured process for both informing and engaging citizens in policy-making. Participants in a citizen assembly are presented with facts and real constraints around predefined topics, and then work together in a facilitated process to formulate recommendations for the political leadership. As such, they get to understand in depth the constraints faced by politicians when weighing different policy options. In Tallinn, during the Green Capital year 2023, a citizen assembly asked a group of around 60 pre-selected citizens from various demographic backgrounds about how to better connect the city’s green spaces into an urban whole. The recommendations were then presented to the city council. In this way, allowing people to step into the shoes of policy-makers helps to address issues that become targets of political polarisation.

For the NGO behind the Swedish ridesharing movement, Skjustgruppen, the founder Mattias Jägerskog explained that the work they do is indeed political (albeit not linked to any political party). They want to contribute to opinion-building around climate change and sustainable development in Sweden, as well as to democracy overall. That’s why their carefully designed definition and model for ridesharing puts the democratic process at the centre: people get together, make a collective decision, and act on that decision. Referred to the “ridesharing wheel” or “the five parts of ridesharing” shown below, it helps explain the bigger picture of a seemingly simple act of going from A to B, together.

The “Skjutsgruppen model”, which is simple and yet gives a structured process for engaging citizens in democratic processes and sustainability, is an interesting one to consider in other fields of citizen engagement for sustainability as well, like community gardens, housing projects, energy saving and more.

Walking the fine line as a civil servant

To sum up, the work on engaging citizens in sustainable development requires some careful consideration, especially in the current context where political polarisation and disinformation abound. Civil servants need to work within this context, helping to provide stability and engage citizens in long-term sustainable development goals that benefit their communities for generations to come. Yet, they must do so in a way that fulfills their specific role and does not run counter to democratic processes and values.

In this article, we presented four strategies that can help to make the work of civil servants politically “neutral” when meeting a divided public, and keep debates as sound and open as possible to allow for political opinions and choices to form. Using science, highlighting co-benefits, avoiding “jargony” language, and making use of established methods like citizen assemblies are all tools that are at the hands of civil servants to help this quest.