Rethinking sustainable mobility and public spaces in villages through trust, proximity and creativity

For years, rural planning has too often relied on importing urban solutions. But this approach ignores the rural world’s intrinsic strengths: a sense of community, proximity to nature, and their own social and cultural values. Instead of borrowing from the city, rural areas must draw on their own identity to develop responses that are rooted in local realities, and shaped by the specific needs and opportunities of each territory.

What if, instead of trying to make villages act like cities, we recognised rural areas as places of innovation in their own right, not just scenic backdrops or nostalgic landscapes, but vibrant spaces built on trust, proximity, and creativity?

Less is more: rethinking rural mobility

Rural mobility is often seen through the gaps: sparse transport options, long distances, and very little budget to go around. But scarcity can also spark creativity. We’ve seen that when communities start from what they do have — trust, proximity, creativity — they can build smarter, more integrated mobility systems from the ground up.

These systems are not based on infrastructure alone, but on relationships, local governance and participation. Mobility becomes more than transport: it becomes a form of care, connection and shared responsibility.

Benches with a purpose: mobility starts at the crossroads

One of the most delightfully simple — yet quietly revolutionary — examples come from Germany: the ride-sharing bench (to the picture above).

It’s exactly what it sounds like. A bench, placed strategically on the edge of a village, with a sign indicating its purpose. Sit down, and you’re signalling that you need a lift. No app, no booking system, no bureaucracy. Just human interaction and local trust.

These benches show us how civic infrastructure can be informal but effective, and how mobility doesn’t need to be digital to be smart. They work because they’re rooted in rural culture: neighbourliness, visibility, and mutual aid.

They are also:

- Low-cost: just signage, seating and communication.

- Highly visible: easily spotted by drivers.

- Transferable: adaptable to different contexts with minimal investment.

Sometimes, a bench is smarter than an algorithm.

Citizen buses: transport as social infrastructure

In Belgium and Austria, villages have created citizen-led bus schemes to bridge transport gaps. These aren’t commercial ventures, they’re locally managed services, often run by volunteers or semi-public entities.

They typically serve:

- Older residents needing to reach healthcare or markets.

- Students getting to school in areas without regular buses.

- General residents travelling between villages or to regional centres.

What makes them special is the way they combine flexibility, care and local governance. Some run fixed routes; others operate on-demand. Many are embedded within care cooperatives or municipal programmes.

They prove that rural transport can be relational and inclusive. They also demonstrate that mobility is, above all, a public good.

From Post-Its to parklets: recognising the informal

The Post-It City project, originally developed by the CCCB in Barcelona, mapped informal and spontaneous uses of public space: street markets, unofficial taxi stops, outdoor prayer areas, or pop-up gathering spots.

In rural areas, these practices often go unnoticed — but they’re everywhere. The dusty patch outside the school gate where parents wait. The corner by the shop where older neighbours meet. The unused lot that turns into a fairground once a year.

The key lesson: planning must start with observation. Planners should see what’s already happening before drawing new lines on the map. Recognising informal practices means respecting rural rhythms and identities.

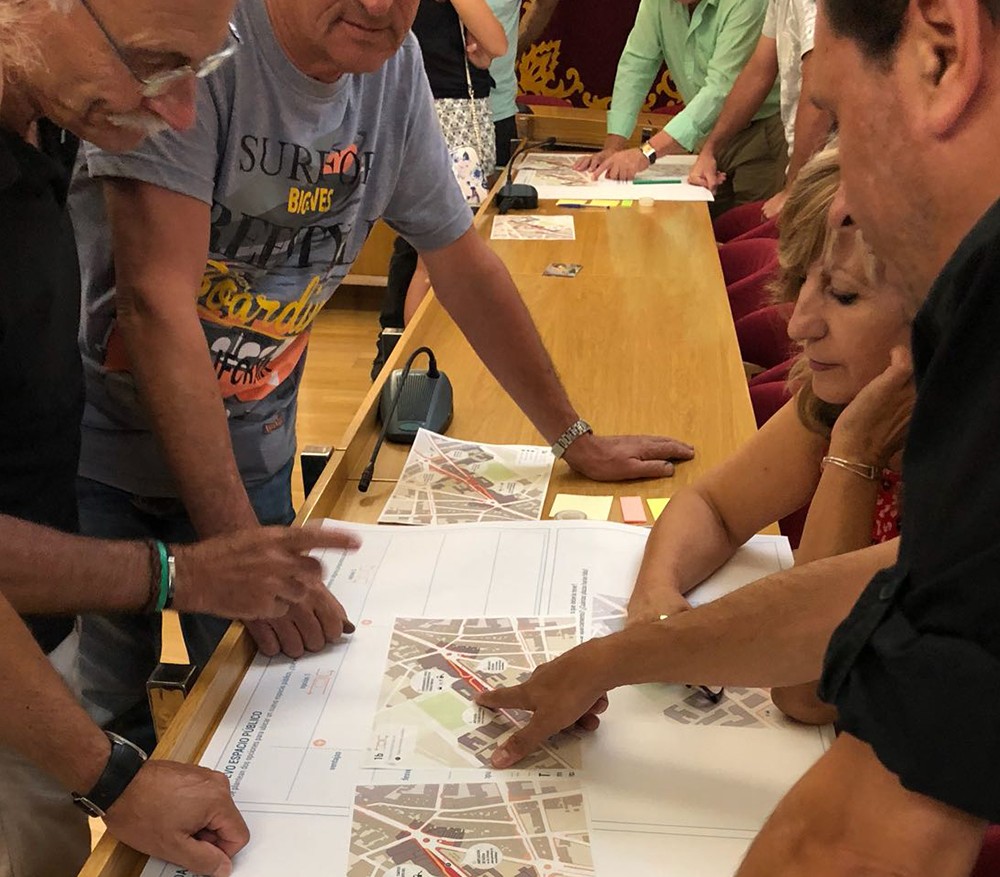

Aspe Complete Streets: a road for everyone

In Aspe, a town in rural Alicante (Spain), the Complete Streets concept was adapted. The redesign of one of the town’s main axes made room for pedestrians, cyclists, shade, and social life… turning what was once just a road into a truly liveable street.

What stands out in Aspe is the process:

- Participatory design with local residents.

- Rebalancing mobility: fewer lanes for cars, more for people.

- Green infrastructure: trees and permeable surfaces for climate resilience.

- Microspaces: benches, shade structures and resting spots for intergenerational use.

This wasn’t a cosmetic facelift. It was a strategic shift: designing a street as a platform for rural life, combining accessibility, ecology and community.

Pradogrande Park: a rural infrastructure of care

Near Madrid, in the town of Torrelodones, Pradogrande Park was once an underused green area on the periphery. Through a co-design process led by Paisaje Transversal, it was transformed into a multifunctional rural park.

What makes this case remarkable is how it redefined what a park can be:

- A space for learning and play, co-designed with schools.

- A space for care and health, connected to walking routes and older adults.

- A space for ecological continuity, with rainwater management and local flora.

It’s not just a park — it’s a piece of rural infrastructure that blends landscape and social function.

Accessible villages: designing for dignity

Accessibility is often overlooked in rural planning. But the "Accessible Village" model, developed in Italy, brings inclusion to the forefront.

Villages carry out audits with residents —especially older people, people with disabilities and children— to identify physical barriers: stairs without railings, narrow pavements, poor signage.

Solutions are simple, affordable, and impactful:

- Better lighting.

- Smoother surfaces.

- Clearer signage.

- Accessible entrances to public buildings.

The result? A village that’s more comfortable for everyone — and more welcoming to visitors, families, and future generations.

Tactical urbanism: low-budget, high-impact

Tactical urbanism is often misunderstood as colourful paint and Instagram moments. But when done well, it’s a powerful tool for rural transformation.

But let’s be clear: tactical doesn’t mean superficial.

Done right, tactical urbanism is not about colourful paint or festival vibes. It’s about prototyping ideas before making them permanent. It’s about engaging people in design by doing. And it’s about embedding small actions in a larger, strategic vision.

Here are some adaptable ideas for tactical urbanism interventions in rural areas:

- Village test days: temporary street closures for markets or festivals.

- Mobile shade modules: benches and planters that travel between neighbourhoods.

- School route experiments: safe walking paths designed with children.

- Reimagined bus stops: add a chalkboard, book exchange or info panel.

- Community pocket parks: low-cost activations of vacant lots.

These aren’t decorative. They’re strategic tools to build support, test change, and shift perceptions.

Learning from URBACT: networks that inspire

URBACT is full of networks experimenting with rural mobility and placemaking. If your municipality is exploring sustainable mobility and placemaking, look to networks like:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Past networks like CityMobilNet, Thriving Streets, and SPACE4People also offer practical tools, templates and case studies.

|  |  |

And remember: It’s not about copying, but adapting!

Building rural futures together

The lesson from all these stories? Rural transformation doesn’t need to copy what cities do. It needs confidence, creativity, and working together.

A ride-sharing bench. A bus stop with a bookshelf. A park designed with children. These aren’t luxuries: they’re essential for rural life with dignity, care, and energy.

So next time someone says your town is “too small” for new ideas, invite them to sit on a ride-sharing bench. They just might catch a lift into the future.